Lifesavers Underground’s Shaded Pain Brought Goth-y Gloom to Christian Music (Review)

One thing that I really hope people will come to realize through reading Opus is how vital and invigorating Christian music can be when it’s not constrained by some need to be “uplifting” and “encouraging.” (Or, to borrow a phrase from Andy Whitman, when it decides to be something more than just “soulless Infomercials for Christ.”)

Look beyond the wasteland that is so often “Contemporary Christian Music” and you’ll find artists who chose to thumb their noses at the party line. Artists who insisted that their Christian faith found its fullest expression in music that might have discomfited pastors, youth group leaders, parents, and Christian book stores even as it still rang with truth, love, and grace.

There’s Larry Norman, the original Christian rocker, who condemned racism and poverty while reaching out to the burnt out hippies that the Church had abandoned. Steve Taylor ruffled feathers by poking fun at televangelists and condemning abortion clinic bombings. Scaterd Few raised eyebrows with their chaotic stories of inner-city life. And The Violet Burning and The Prayer Chain took a page from the Psalms and wrote dark, turbulent songs about their doubts.

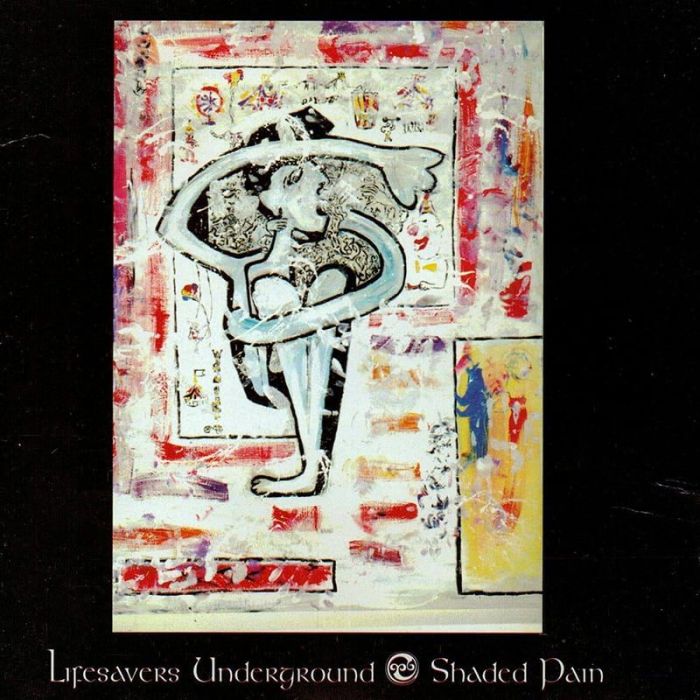

Any such list of artists would be incomplete, though, without a mention of Michael Knott’s Lifesavers Underground and their magnum opus, 1987’s Shaded Pain. Released by Frontline Records — which was already dancing on CCM’s edge via releases by Altar Boys and Mad At the World — I can only imagine the shock that Shaded Pain sent through the Christian music industry of the day.

With a dark, gloomy sound hewing far closer to the likes of Nick Cave and Bauhaus than any CCM contemporary, Shaded Pain found Knott et al. making music that’s still fresh, vital, and absolutely captivating, even after more than three decades. Much of that’s due to Knott’s haunting voice, which alternates between soaring (“Bye Bye Colour,” “I’m Torn”) and searing (“Die Baby Die,” “More to Life”), and his equally haunting lyrics.

You won’t find much church-friendly imagery in these ten songs, but rather, oblique and sometimes creepy lyrics revolving around death and mortality. On “Bye Bye Colour,” Knott sings of an “old man in my backyard/So cold is his flesh, it’s an ivory fire” who eventually brings selfish people to ruin. In response, all Knott can do is lament (“Goodbye, bye, colour/So blue is my heart”). “Lonely Boy” is a sordid story of broken hearts inspired by guitarist Brian Doidge’s own experiences and Lord only knows what Knott’s referring to when he’s wailing about a plague of flies on that particular track.

But even when Knott does include some more obvious Christian imagery and themes, they come with a dark undercurrent. “Die Baby Die” contains this admonishment: “You’re fighting with a passion/But you can’t afford to pave the way/Christ be your salvation/Turn your heart and say… Die, baby die.” Though a likely reference to dying to one’s flesh, it’s still the sort of lyric that makes youth pastors do double takes. That could also be said for the whole of “More to Life” and its criticism of religious leaders who abuse their power (“Death to your ministry/It’s just a joke to me”).

“Our Time Has Come” finds Knott boldly proclaiming “Your god is dead and our God will never leave us” — but only after he sings ominously about kissing the cleaver. Finally, “I’m Torn” not only features Knott’s best vocal performance on the album, but also contains some of his most poetic lyrics as he sings of being torn (npi) between the carnal and the spiritual:

This one sings me love songs with a kiss so sweet.

She never smiles, yet is always on my mind.

And the other one calls with a love so true,

Taking my heart, making it new.Both have winds that sing me songs.

Which sea shall I sail upon?

Notably, the song ends without Knott answering his own question. It’s an ambiguity that makes the song so much more powerful and human — but it’s also anathema in those Christian circles where faith has to be restored and the Christian must experience “victorious living” by the time the bridge comes around.

Shaded Pain concludes with the sparsely beautiful title track, a piano ballad about human frailty and suffering, and the Church’s own potential role in all of that:

What about love, the love we never find?

Cut by the body, forced to run and hide.

What about the human, the human I am inside?

How can we be forgiven if we don’t live our lives?

Musically, Shaded Pain goes right for the jugular and never lets go, thanks to Brian Doidge’s guitar. Doidge and Knott began playing together around 1980, and Doidge would be Knott’s right-hand man for many years. But the two were never more in sync than here on Shaded Pain.

Doidge’s Les Paul Goldtop spreads across “Bye Bye Colour” like shadowy tendrils, quite appropriate given the song’s morose lyrics. In contrast, that same Les Paul is all sharp, slashing edges on “Die Baby Die,” and as a result, the song sounds like something you’d hear on a seedy dive bar jukebox during a biker brawl. Doidge’s guitar is all swagger on “Our Time Has Come” and punky riffs on “Tether to Tassel,” and it conveys an urgency on “I’m Torn” that perfectly complements Knott’s anguished lyrics.

Some have criticized Shaded Pain for being too dark and gloomy, which is understandable. Although the music is often bracing in the best punk/garage rock tradition, there’s nary a ray of hope in any of Knott’s lyrics. (It’s not too surprising to learn that Knott was banned from performing in several churches following Shaded Pain’s release.)

But at the same time, there’s also nary a hint of dishonesty or insincerity in these songs. I’m reminded of something Wovenhand’s David Eugene Edwards (another Christian artist flourishing outside the boundaries of CCM) said about his musical tastes and evolution:

I think God used other music, more aggressive, kind of darker music to stir up my soul. I guess I grew up around a lot of sad things so it was very easy and comfortable… for it to be part of my life. And that’s what attracted me probably to music like Joy Division and The Birthday Party or Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. Music that people would say,“Oh, this is depressing music, dark music.” What I find beautiful in the music that I was attracted to was people were being very honest. I felt like Ian Curtis was being very honest with me when he was singing to me. I felt like Bon Scott from AC/DC was being very honest with me when he sang to me. And even though it was stuff I did not agree with, I thought it was very sincere.

Shaded Pain is not an album for everyone, nor should it be. It’s an album practically designed — though not, I think, with express malice — to disconcert religious authority figures. But I think it was (and still is) a helpful counter to certain notions of what Christian music can or can’t be, what it should or shouldn’t sound like. And for those listeners who do “get it,” Shaded Pain’s goth-y gloom speaks truth about our brokenness and frailty with an intensity that few Christian albums have matched, then or now.