Howard Pyle’s Men of Iron: A Fanciful Coming of Age Story in the Middle Ages (Review)

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Howard Pyle was one of America’s preeminent artists. He illustrated numerous articles for publications like Chicago Tribune, Collier’s Weekly, and Harper’s Weekly, and delved into mural painting near the end of his life. He even launched his own art school (popularly called the Brandywine School) in 1900 with the goal of creating a distinctly American style that could hold its own with the European schools.

In addition to being a prolific artist, Pyle was also a prolific author, especially of children’s stories. While he wrote numerous stories for younger audiences, he’s perhaps best known for his stories that occur during the Middle Ages and/or deal with stories of knights and chivalry. These include imaginative, influential re-tellings of the Robin Hood and King Arthur legends as well as more realistic stories like Otto of the Silver Hand and Men of Iron.

First published in 1891, Men of Iron is a coming of age story about young Myles Falworth, the son of a disgraced nobleman who enters the world of chivalry in the hopes of restoring his family’s honor. Set in 15th-century England during the reign of Henry IV, Men of Iron is filled with historical detail (including one chapter that describes the actual knighting ceremony at great length) that is nonetheless rendered in a very fanciful, and even romantic manner.

This occasionally means that Myles can seem less like a living, breathing person and more a stand-in for Pyle’s own fanciful view of the era. There’s very little dramatic tension; this being a “coming of age” story, it’s pretty clear how things are going to end up for Myles and his family, even if he experiences some bumps and bruises along the way. Chivalry, honor, and virtue will always triumph in the end.

The romanticized manner in which Pyle tells his story is one of the reasons why I love it. An author like George R.R. Martin has made a career out of deconstructing classic fantasy tropes that involve brave knights performing noble deeds of heroic gallantry. But while I enjoy Martin’s writings for their grittier, more complicated view of human nature, there’s something delightful about Pyle’s more idealized view in which honor, nobility, and chivalry exist and their virtue is never doubted. (And yes, Pyle was writing primarily for children and Martin is most definitely not, so the comparison shouldn’t be pushed too far.)

And then there’s Pyle’s prose. While it can sound awfully florid and stylized to modern ears, what with all of the “thees,” “thous,” “prithees,” and “methinks,” there are certain passages that are particularly thoughtful, beautiful, and even insightful. For example, this passage, which anyone who knows what a find a good secret hiding place can be will appreciate:

Perhaps there is nothing more delightful in the romance of boyhood than the finding of some secret hiding-place whither a body may creep away from the bustle of the world’s life, to nestle in quietness for an hour or two. More especially is such delightful if it happen that, by peeping from out it, one may look down upon the bustling matters of busy every-day life, while one lies snugly hidden away unseen by any, as though one were in some strange invisible world of one’s own.

And then there’s particularly vivid description of winter in a 15th-century castle:

Then fall passed and winter came, bleak, cold, and dreary — not winter as we know it nowadays, with warm fires and bright lights to make the long nights sweet and cheerful with comfort, but winter with all its grimness and sternness. In the great cold stone-walled castles of those days the only fire and almost the only light were those from the huge blazing logs that roared and crackled in the great open stone fireplace, around which the folks gathered, sheltering their faces as best they could from the scorching heat, and cloaking their shoulders from the biting cold, for at the farther end of the room, where giant shadows swayed and bowed and danced huge and black against the high walls, the white frost glistened in the moonlight on the stone pavements, and the breath went up like smoke.

Finally, this passage struck me with a particular poignancy:

All of us, as we grow older, have in our memory pictures of by-gone times that are somehow more than usually vivid, the colors of some not blurring by time as others do.

Even though modern readers may scoff at Pyle’s romantic view of a young squire’s life in the Middle Ages, it’s less simplistic than you might initially think. Dig a bit below the florid-ness and you’ll find some grit. Pyle enjoys describing good, chivalrous combat in which knights revel in honest battle to prove their mettle. However, he doesn’t always shy away from the brutality, whether it’s his description of a duel between Myles and another young squire as “not only brutal and debasing, but cruel and bloody as well,” or the brutish images that introduce the novel’s main villain.

As he grows into knighthood, Myles even finds himself questioning the morality of duels and combat in general, leading to an interesting discussion with his priest. And Pyle adds some political intrigue for good measure, as Myles slowly comes to realize that he might just be a pawn in a bigger game. Pyle certainly doesn’t belabor on such themes — to do so too much would detract from his jaunty storytelling — but I was pleasantly surprised when I came across them since they added a bit more dimension to a fanciful boy’s story.

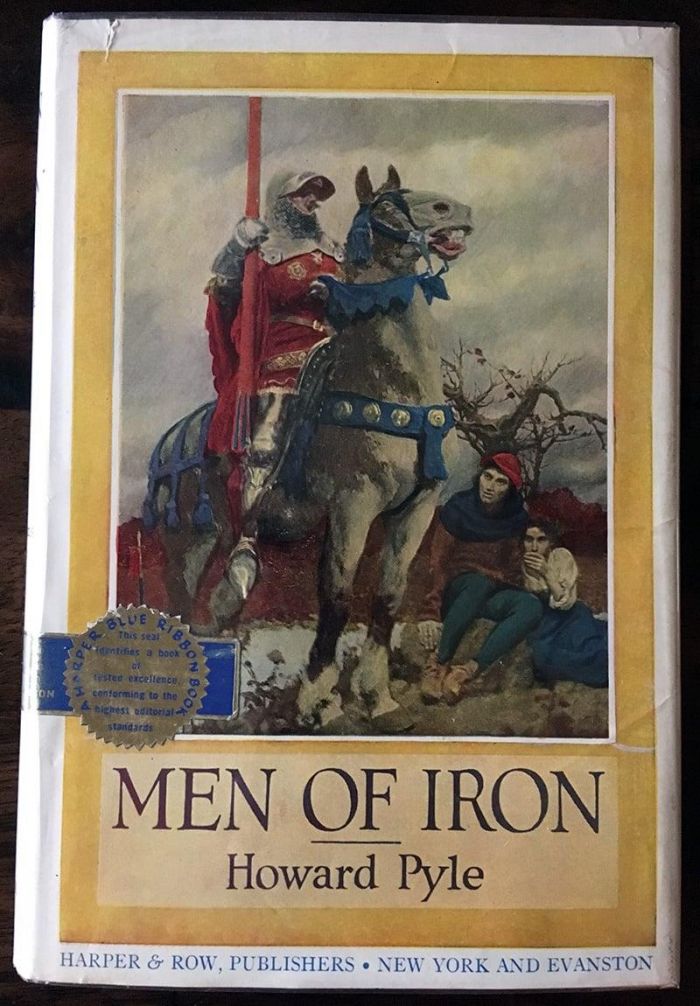

It might seem odd that I haven’t written anything yet about Men of Iron’s illustrations given my love for Pyle’s Arthurian-themed drawings. Pyle illustrated Men of Iron with oil paintings, and while they’re good in their own right, none of them have the same impact as the detailed pen drawings that appear elsewhere in Pyle’s bibliography. As Henry Pitz wrote in his 1965 biography of Pyle (emphasis mine):

The Men of Iron pictures were… well painted but they lack the bite and power of the pen drawings for Otto of the Silver Hand. They are well composed, the forms are there, the figures characterized, but the method of reproduction has sapped the contrasts and encouraged the shapes to be factually accurate rather than imaginatively arresting. The eye travels over the gray panels without much temptation to linger and find long satisfactions.

C.S. Lewis once wrote that “a children’s story which is enjoyed only by children is a bad children’s story.” In other words, good stories are good stories, regardless of the age group that such stories are supposedly for. Even adults ought to find something enjoyable in a well-written story for kids. (Here, another Lewis quote is apropos: “When I became a man, I put away childish things, including my fear of childishness and the desire to be very grown up.”)

That’s my reaction to Men of Iron, anyway. There’s much about it that’s out of step with modern sensibilities, both with regards to fantasy storytelling and children’s storytelling. But that, combined with Pyle’s obvious love for history and writing about the era, is precisely why I find Men of Iron so refreshing. It doesn’t quite reach the lofty heights of his Arthurian tales, nor does it have the intensity of Otto of the Silver Hand, but it’s still a rousing, strongly principled adventure story that I would’ve loved to read back in 5th grade.