Sayonara, Evangelion

With the long-awaited release of Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time, the fourth and final film in the long-gestating Rebuild of Evangelion project, Hideaki Anno has closed the door on one of the most iconic animation franchises of all time. But despite coming to an end, Evangelion remains a cultural juggernaut.

When it was released in Japanese theaters this past March, Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 smashed box office expectations. Similarly, it set streaming records upon its debut on Amazon Prime Video. Beyond the Rebuild project, GKids is releasing the original Neon Genesis Evangelion series in an impressive, and pricey, limited edition Blu-ray collection that’s chock full of goodies for Evangelion fans — and it’s already sold out.

Put simply, Evangelion has never been bigger. But with all of that success has come plenty of criticism. Evangelion has been accused of being dense and convoluted, with hard-to-like characters, pessimistic and even nihilistic themes, gratuitous fan service, and pretentious artistic and production decisions. (Back in 2019, I wrote an in-depth post that more fully explores Evangelion’s history, popularity, and controversy. It might provide some helpful context for this post.)

I’ve been a fan of Evangelion for decades and consider it a monumental title in many ways. However, I don’t disagree with any of those criticisms. Evangelion is, without a doubt, pretentious, convoluted, and gratuitous, not to mention pretty dark and twisted in places. But it’s also much more than the sum of its parts.

At its core, Evangelion is a deeply personal message from Hideaki Anno about growing up and confronting one’s grief and pain, facing life’s hardships instead of running away from them, and not fearing the hurt and misunderstanding that comes with human relationships. (That Anno himself has struggled with depression and suicide for decades, and fully acknowledges the help he’s received from his wife and mentors like Hayao Miyazaki, lends only more weight to that message.)

Suffice to say, Amazon’s worldwide streaming of all four Rebuild of Evangelion movies is bound to reopen debate and stir up old and new criticisms, especially as viewers try to make sense of the series’ new ending. I say “try,” because I know I’m still sifting through my own thoughts and feelings concerning Anno’s new ending (which he’s described in fairly definitive terms).

Note: The following contains spoilers for the Rebuild of Evangelion films.

Anno’s plans for the Rebuild of Evangelion project were ambitious, to put it mildly. Back in 2007, he released an official statement before the release of the first Rebuild movie in which he laid out such lofty goals as:

- “Share… the embodiment of image, the diversity of expressions, and the detailed portrayal of emotions that animation offers”

- “Fight the continuing trend of stagnation in anime”

- “Create a form of entertainment that anyone can look forward to; one that people who have never seen Evangelion can easily adjust to, one that can engage audiences as a movie for theatres, and one that produces a new understanding of the world.”

To achieve these goals, Anno left Gainax (the studio he helped found in 1984 that produced the original Evangelion titles), launched a new studio called Khara, and reunited with many of the cast and staff from the original series, including assistant director Kazuya Tsurumaki and composer Shirō Sagisu — all with the intent of “creating something that will be better than the last series.”

From a visual and technical standpoint, at least, Anno’s Rebuild is an unqualified success. All four movies look amazing with topnotch animation, incredible character, mech, and vehicle designs, thrilling action sequences, and a nigh-seamless blend of cel and computer animation. Modern live action techniques, such as motion capture and virtual cameras, were integrated into the films’ production. And Anno, ever the auteur, even employed some post-modern flourishes similar to those that proved so controversial during the original series’ run back in the mid ’90s. (How controversial? Anno and Gainax received death threats from fans irate at Evangelion’s original, and highly “unorthodox,” ending.)

In one climactic duel, a pair of giant mechs face off in a series of increasingly preposterous and surreal environments, including an apartment dining room, a watermelon field, and a soundstage. And when it comes to depicting the end of the world, the movie’s animation literally starts breaking down; each subsequent shot grows more basic and reduced, from full color all the way down to rough pencil sketches and key frames. It’s a striking — and artsy — way to depict a character’s existence fading away into nothingness.

Of course, such moments make no logical sense within the movies’ world; they’re the animated equivalent of breaking the fourth wall. All that’s missing is for the characters to turn and address the audience directly. However, by the time Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 enters its increasingly surreal final act — in which characters utter portentous lines like “We’re above the L-c field that rejects all life stained by the original sin,” “Even if they call it ‘God’s Eva,’ it’s just the 13th man-made ultimate multipurpose humanoid decisive weapon,” and “I merely appended upon my body information the transcends the Logos of our realm” — it’s obvious that Anno isn’t terribly concerned with logic and sense.

That’s not always a good thing, as is the case with the third Rebuild movie, 2012’s Evangelion: 3.0 You Can (Not) Redo. The shortest Rebuild movie, it’s also the most incoherent, throwing out new ideas and revelations at breakneck speed. While explaining things has never been Evangelion’s strong suit, it’s hard not to feel like Anno and the Rebuild project lost their way during Evangelion: 3.0. (That sense of lost-ness is only amplified by the fact that Anno not only left the Rebuild project after Evangelion: 3.0 to work on other movies, including 2013’s The Wind Rises and 2016’s Shin Godzilla, but he also experienced a new bout of depression that he blamed on “having spent six years grinding down my soul making Eva again.”)

But Evangelion’s adherence to the “Rule of Cool” (which states that things happening in a story don’t have to make sense so long as they’re really awesome) can make for some exhilarating experiences. This is most obvious during the movies’ many over-the-top action sequences, which defy reason. Watching them, a more skeptical or nonplussed viewer might find themselves asking questions like:

- Does a giant city with skyscrapers that slide underground any time danger arrives really make sense as a battle fortress, especially if it’s supposed to be guarding a vast underground military complex? How much time, labor, and resources go in to ensuring that those buildings remain structurally sound?

- Would you really be able to harness all of Japan’s energy in a matter of hours so that a giant robot could blast an alien invader with a massive sniper rifle?

- Is surfing through waves of enemies on aircraft carriers really an effective way for giant robots to move into battle?

- Do rocket-propelled battleships really make for effective missiles in a battle to prevent the end of the world?

- And if the world really is ending, then where are all of those spare robot parts coming from?

Naturally, the obvious answer to questions like these is a simple Who cares? I, for one, sure don’t, not when the results are as effin’ sweet as what Khara puts on the screen.

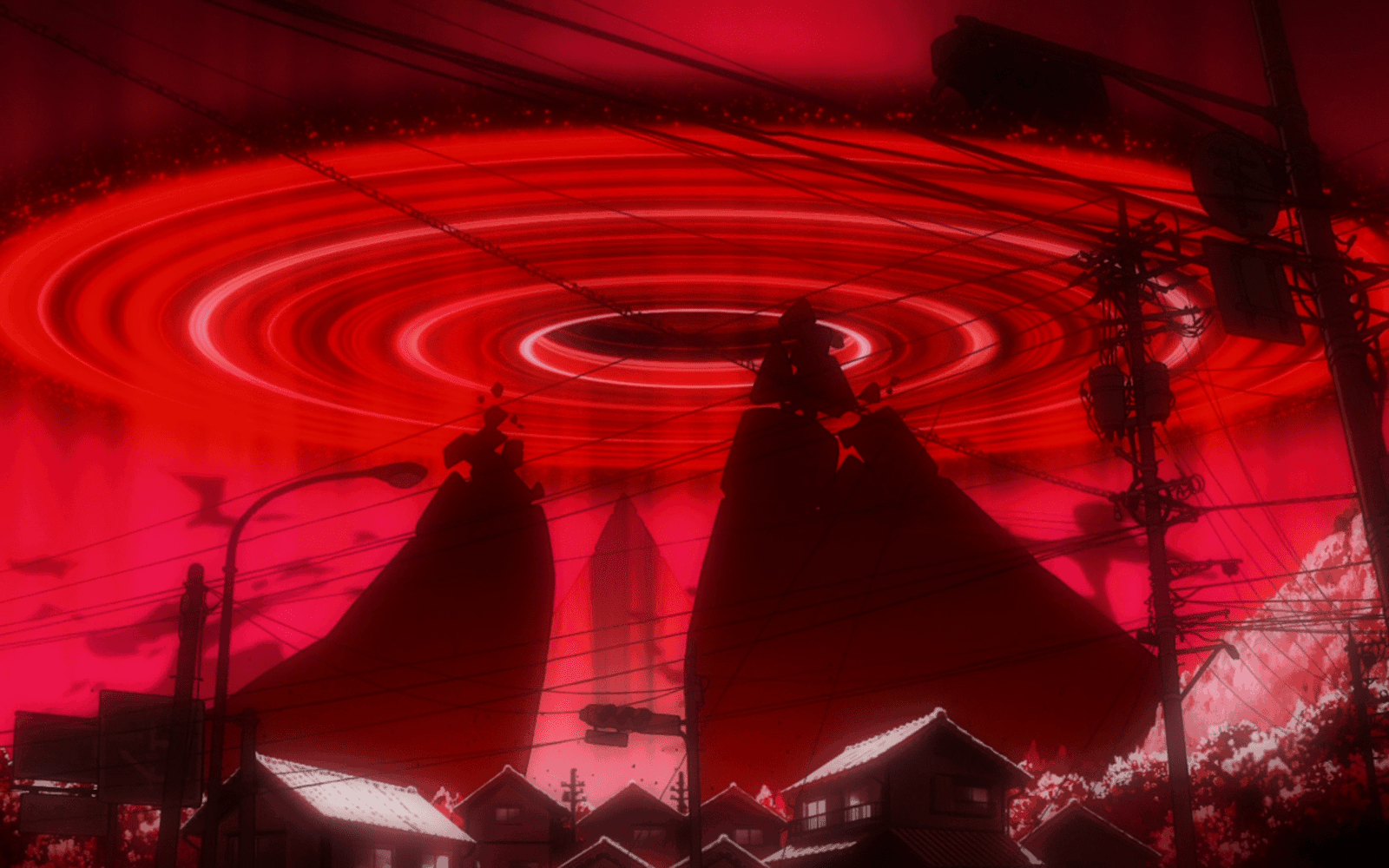

The same principle can hold true for the movies’ apocalyptic spectacles, which are truly unlike anything else in any other medium. With its mishmash of esoteric Judeo-Christian imagery (e.g., Angels, the Door of Guf, Longinus) and cryptic terminology (e.g., A.T. Fields, Human Instrumentality Project, LCL), Evangelion rarely seems interested in presenting a truly coherent and systematic mythology. Rather, it’s far more interested in just overwhelming viewers in order to achieve a heightened dramatic and emotional effect. (That being said, you better believe that an army of nerds is currently hard at work trying to systematize everything in the Rebuild movies, and more power to ‘em.)

The downside to this storytelling approach, however, is that it’s all too easy for the characters and their drama to get drowned out by all of the spectacle. When this happens, Shinji, Asuka, et al. cease being interesting individuals with emotions and stories that the audience cares about and instead, are reduced to being mouthpieces for opaque dialog and/or simple grist for the movies’ sadistic emotional wringer.

This is where Evangelion has always struggled, and that’s particularly so with the Rebuild movies once they finally abandon the original series’ storyline for Anno’s new vision. There’s enough action and spectacle for a dozen anime series, but as for a storyline that connects on an emotional level in the midst of all that? That’s not always the case.

The first two movies — 2007’s Evangelion: 1.0 You Are (Not) Alone and 2009’s Evangelion: 2.0 You Can (Not) Advance — adhere pretty closely to the original series’ storyline. In fact, Evangelion: 1.0 is basically a retelling of the first six episodes, beginning with Shinji Ikari’s arrival in Tokyo-3 at the behest of his estranged father, Gendo Ikari.

Rather than a reunion, though, Gendo presses the timid Shinji into service as the pilot of an Evangelion (Eva), a massive robot created by the government agency NERV to defend humanity against otherworldly invaders called Angels. Evangelion: 1.0 is fairly episodic in nature, but the consistent theme is Shinji’s increasing sense of isolation and trauma due to piloting an Eva and battling Angels.

Evangelion: 2.0 contains plenty that’s familiar, as well, specifically the headstrong Asuka, a fiery Eva pilot who takes an immediate dislike to Shinji. But new wrinkles appear in the story, including a new Eva pilot (the boisterous Mari Illustrious Makinami), a deepening personality for the enigmatic and doll-like Rei Ayanami, and even hints of a romantic triangle forming between Shinji, Asuka, and Rei. There’s also an alternate take on one of Evangelion’s most gut-wrenching scenes, in which Shinji is forced to sit helplessly as Gendo commandeers his Eva to battle a fellow pilot — with horrific results.

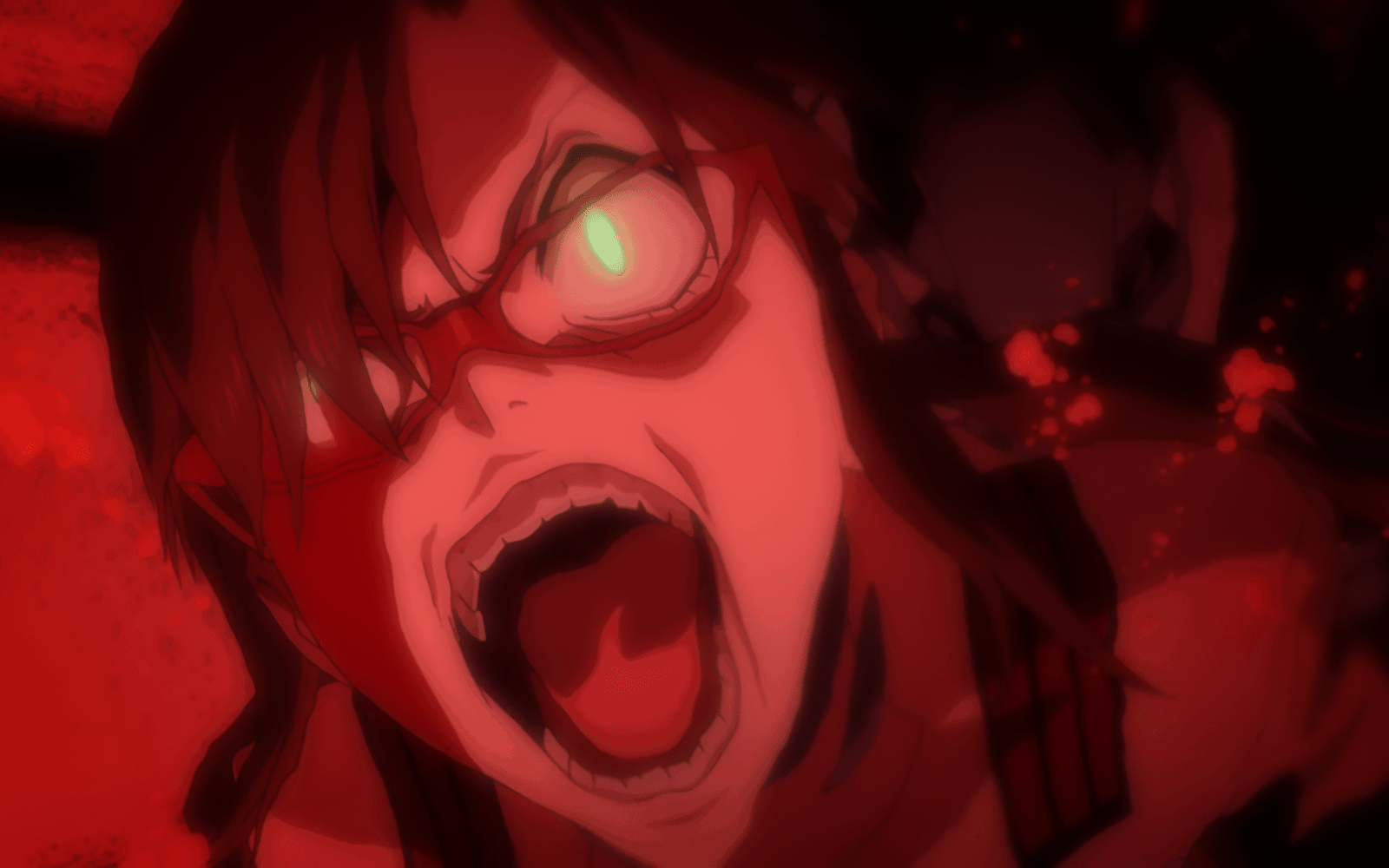

But by its second half, Evangelion: 2.0 has turned entirely towards uncharted waters, with Shinji — who has become thoroughly traumatized and disgusted by his father’s callous treatment — unwittingly initiating the apocalypse. The unabashed spectacle is one of the first instances of Khara’s animators truly cutting loose. It’s also the moment when the Rebuild starts to lose focus, character and story-wise.

What should be a tragic moment for Shinji, who’s driven by trauma and a desperate awareness of his own uselessness, as well as everyone else suddenly caught up in the end times, instead gets swallowed up by an extravagantly apocalyptic display that ends up obfuscating any sympathy for the characters’ terrible plight.

This situation doesn’t improve with Evangelion: 3.0, which — as mentioned earlier — is the Rebuild’s weakest movie. That’s unfortunate because it contains massive developments and ramifications for Evangelion’s new storyline. The world has somehow survived the events of Evangelion: 2.0, but it’s a harsher place — something Shinji quickly learns when, upon awakening in this strange, new world, he’s immediately fitted with an explosive collar.

Unbeknownst to him, fourteen years have passed since he nearly ended the world, and though he sees familiar faces — including Asuka, Mari, and even his former caretaker, Misato Katsuragi — they’re now filled with contempt and suspicion. As for Gendo, he’s still in charge of NERV (which is a shadow of its former self) and is fixated on the Human Instrumentality Project, which he hopes will reunite him with his dead wife, Yui — and he’s perfectly willing to use his own son as a tool to achieve that goal.

Shinji’s arc of trauma and isolation comes to a head when he finally meets somebody who treats him like a true friend — only for any possibility of friendship and acceptance to be cruelly snatched away by his father’s machinations. Shinji’s tired of being alone and feeling purposeless; he’s desperate for attention and desperate to atone for his past deeds. And because he’s Shinji Ikari, this causes him to act foolishly and recklessly. (Indeed, the Rebuild movies do little redeem to Shinji’s status as one of the most pathetic heroes of all time.)

For a normal fourteen-year-old, that wouldn’t be a big deal. But in Evangelion, it means that, yes, Shinji ends up initiating the end of the world… again. And this time, it costs him the one true friend he’s ever had, an experience that leaves him catatonic in a way that the apocalypse never could.

As the fourth and final Rebuild movie, Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 had some considerable work to do in order to achieve anything resembling a satisfying conclusion (which explains its two-and-a-half-hour runtime). And to be perfectly honest, I’m still unsure as to the degree of its success. And yet, Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 has moments that are fascinating, gutsy, and deeply affecting.

Evangelion 3.0+1.0 contains as much apocalyptic weirdness and spectacle as the other three films put together (if not more), with imagery and action sequences that border on absolute lunacy. But its most unconventional sequence is also its most mundane, bucolic, and peaceful. After wandering through the ravaged Japanese countryside, which has been turned blood red by fallout from the apocalypse, Asuka, Rei, and the still-catatonic Shinji arrive at a settlement of survivors trying to eke out a simple, peaceful existence amidst the devastation.

If it weren’t for the shattered, crimson landscape littered with giant, headless Eva corpses, you might almost forget that you’re still watching an Evangelion movie. During this sequence, Rei finally begins to develop a personality of her own while Shinji slowly, painfully begins to heal from all of his trauma and guilt. The presence of several minor characters from the first movie, now adults striving to build a peaceful and productive community, helps tie the series’ storylines together while offering a respite from (most of) the post-apocalyptic mumbo-jumbo.

Of course, this being Evangelion, we must eventually return to all of that mumbo-jumbo, and when that happens, it’s an absolute blitzkrieg of bizarre mech combat, esoteric technobabble, post-modern deconstruction, and psycho-analysis. Not only is such a mélange precisely what you’d expect from Evangelion, but it works better here than in Evangelion: 3.0. That’s largely thanks to the aforementioned pastoral sequence, which helps ground the movie and introduces some welcome character growth — most notably in Shinji, who has always felt pretty static in his mopey-ness. That’s not to say it’s anything approaching coherent, though.

But whereas Evangelion: 3.0’s incoherence felt like the result of waywardness and a burned out director, Evangelion: 3.0+1.0’s incoherence feels more purposeful. The onslaught of terms and ambiguous concepts are almost certainly Anno tweaking geek/otaku culture and its need to catalog every. Single. Reference. But on a more serious note, I think Anno et al.‘s efforts are not all that dissimilar from expressionism’s usage of stark and disconcerting imagery to overwhelm and produce emotional responses.

In any case, it’s definitely not subtle, particularly when Shinji and Gendo finally — finally! — take a moment to sit down, open up, and be honest with each other. (After a ludicrous Eva battle, of course.) Some viewers will undoubtedly feel annoyed by how “too little, too late” this moment feels, and that any reconciliation between the Ikaris is unearned. But there’s something affecting about the scene’s unabashed bluntness and urgency, as if Anno’s trying to condense four movies’ worth of emotional honesty and healing into a few minutes.

The more I’ve reflected on his new ending, the more I realize that Anno was walking the line between the original series’ ending and that of 1997’s The End of Evangelion. The former dove deep into philosophy and psycho-analysis, as Shinji sought desperately after any justification for his existence, and ends up in a place of belonging. The latter, on the other hand, fully embraced the apocalypse, delivering a blood-soaked and nightmarish finale that represents Evangelion at its most nihilistic, and ends in a place of utter despair. With Evangelion 3.0+1.0, you get a little bit of both. There’s darkness, violence, and sacrifice aplenty in Evangelion 3.0+1.0’s final moments, but also hope, healing, and growth.

Again, I’m not sure how well it all holds together; even with its extended running time, Evangelion 3.0+1.0 still feels over-stuffed and crammed together. But I won’t deny getting a bit choked up whenever I think of the movie’s very last scene, in which Anno sends some familiar faces out into a bright new world to the strains of Hikaru Utada’s “One Last Kiss.”

When Utada sings “I love you more than you’ll ever know,” there’s a part of me — the part that’s spent untold hours scouring message boards and discussion forums in order to clear up yet another one of Evangelion’s ambiguities — that likes to imagine those words are Anno’s ultimate statement.

Yes, it’s easy to be cynical about Evangelion, be it the storyline, the fan service, the cluttered mythology, or even the way in which Gainax has merchandised the franchise to within an inch of its life. Lord knows I’ve rolled my eyes at it plenty of times, even while watching the Rebuild movies. But when you get to the heart of the story, it ultimately comes from a place of love: love for the characters, love for its madcap, elaborate, and utterly unique world, and even love for the audience. Love, and a desire for healing and growth. As James Whitbrook writes:

Our heroes are allowed to heal, to move on from the hurt that defined them as we once knew them, and say goodbye to Evangelion forever. There can be no more Evangelion, for the ultimate power of this world, of our own, is not a legion of building-sized deified cyberorganic metaphysical weapons of Man and God, but our ability to be open with others, to care for them, to forge sincere, loving bonds with one another. This boundlessly hopeful ending is not in contrast with the ends that Evangelion has faced before, it’s in conversation with them. It’s a continuation and maturation of a hope that has woven the entire franchise together for decades, often in spite of Eva’s burdensome reputation as a subversive, gritty, and cumbersomely edgy metacommentary on mecha anime as a genre.

There’s never been anything like Evangelion in any medium, and there never will be. And now it’s finally over. The fates of Shinji, Asuka, et al. have been sealed but their futures are wide open. As is Evangelion’s wont, there are still mysteries left unsolved and questions left unanswered, but we can now move on with our lives — just like Hideaki Anno wants us to.