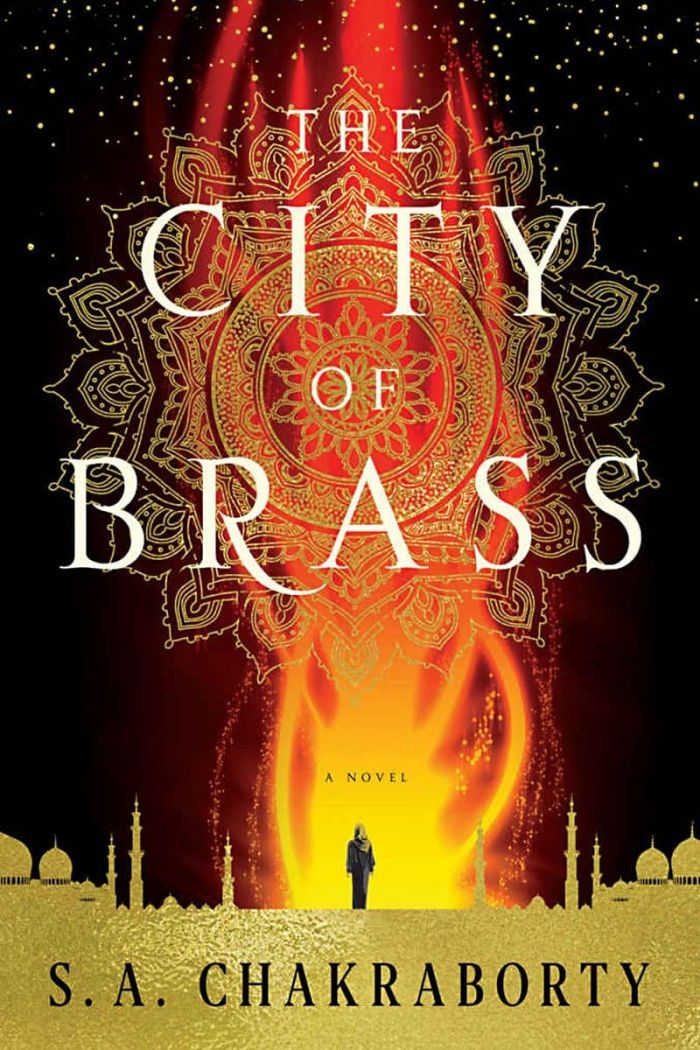

S. A. Chakraborty’s Captivating City of Brass Is a Refreshing Fantasy Debut (Review)

I have a confession to make: most of the fantasy authors and stories that I read and enjoy — e.g., Gaiman, Martin, Bujold, Rothfuss, and of course, Lewis and Tolkien — are distinctly Western in origin, having been influenced by everything from Arthurian and Celtic legend to European geography, history, and politics. And I suspect that’s true for many fantasy fans. For better or worse, the genre is dominated by Western influences.

Which partially explains why S. A. Chakraborty’s The City of Brass was such a refreshing read. Set in 18th century Cairo, Chakraborty’s debut draws entirely from Islamic and Middle-Eastern religion and lore as the sources for its world-building. Hers is a world filled with djinn and ifrits, shedu and rukhs, sheikhs and flying carpets — and one I found quite captivating from page one.

Nairi is a young woman who survives in war torn Cairo as a hustler, grifter, and con woman. And though she dismisses magic and the supernatural, she also possesses strange abilities — she can detect and heal sickness as well as rapidly understand languages — that prove useful to her cons, but leave her anxious and confused about her identity and heritage. When her abilities accidentally summon a fearsome djinn warrior named Dara during her latest con, questions of her identity and heritage suddenly become deadly as she finds herself caught in a struggle between otherworldly forces.

Her only hope for safety now lies in reaching the hidden city of Daevabad, the titular city of brass and magical home of the djinn (or “daeva,” as they prefer to be called). There, she might discover some answers about her past. But Daevabad is rife with its own dangers, as tensions grow between the various daeva clans as well as between daeva and shafits (i.e., the mixed-blood offspring of daeva and humans) — and Nairi’s arrival threatens to set everything off even as she struggles to understand who she really is.

The City of Brass bears some of the flaws of a debut novel. Its pacing can be stilted; Chakraborty’s mythology is always fascinating but occasionally grows too convoluted for its own good; and some important plot threads seem to disappear entirely from the novel (though, presumably, they’ll be picked back up in the upcoming sequels). Does The City of Brass sometimes fail to live up to its ambition? Yes, but honestly, I’d rather have that than a novel that doesn’t try to be ambitious at all.

I ultimately found it easy to overlook such issues for several reasons. First are the novel’s aforementioned non-Western inspirations, which are a breath of fresh air and fill the pages with truly fantastical ideas and exotic images that are more than just simple window-dressing. (Mere Orientalism, this most certainly is not.) Second is that Chakraborty writes some truly lovely prose that’s a joy to read. For example:

Though the adhan, the call to dawn prayer, rang out across the wet air, there was no sign of the sun in the misty sky. Fog shrouded the great city of brass, obscuring its towering minarets of sand-blasted glass and hammered metal and veiling its golden domes. Rain seeped off the jade roofs of marble palaces and flooded its stone streets, condensing on the placid faces of its ancient Nahid founders memorialized on the murals covering its mighty walls.

And finally, while the novel is primarily about Nairi’s magical quest to understand her true nature, The City of Brass also tackles issues of colonialism, ethnic identity, racial tensions, and the ethical compromises endemic in wielding power. While Nairi and Dara face dangers and hardships in their journey to Daevabad, a devout-yet-naïve young prince named Ali finds himself torn between the privilege he enjoys and the ethical demands of his faith — demands that find him potentially betraying his father, the king of Daevabad, to offer aid to the shafits in their struggle for equality.

The inclusion of such social issues could easily become heavy-handed and even preachy, but they feel organic to the story because they’re presented from within character’s perspectives so well. Ali’s horror at the shafits’ plight, Nairi’s struggle to live up to a legacy she never knew about, and even Dara’s struggles with his troubling and violent past… all of these things lend further depth and intrigue to the magical world that Chakraborty weaves from page to page.

Finally, I have to admit to initially being a little disappointed upon learning that The City of Brass was the first novel in a trilogy. When I finished it, I assumed the novel was standalone, and while some important plot threads had been left unresolved, I actually found it interesting to have been left in a state of open-endedness regarding the characters’ fates. That being said, I absolutely plan on reading The Kingdom of Copper when it comes out in 2019, reuniting with Nairi et al., and returning to the city of Daevabad with all of its magic, wonders, and terrors.