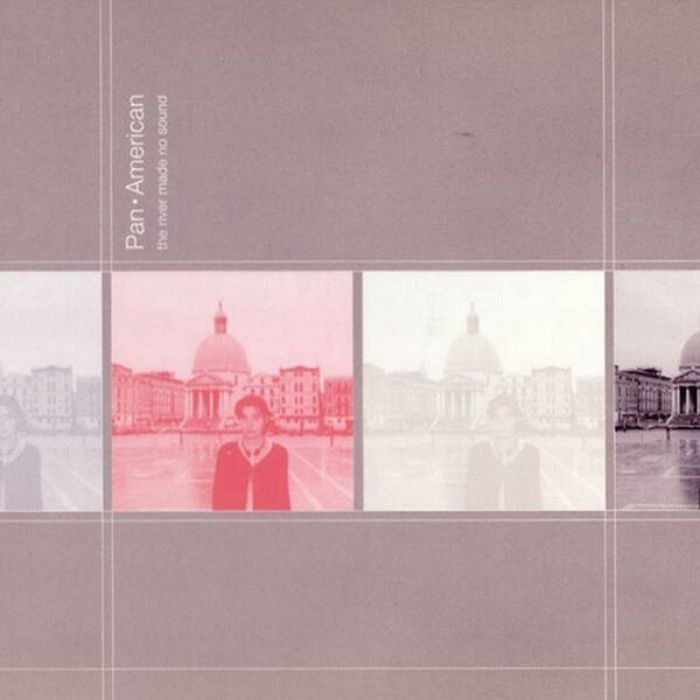

The River Made No Sound by Pan•American (Review)

Through his work with both Labradford and his solo project, Pan-American, Mark Nelson has developed an incredible eye for detail with his soundscapes. However, it’s the sort of detail that only reveals itself after several listens. That’s especially true with his work on Pan-American. You’d be forgiven for not even knowing one of his CDs was playing until it was over, and silence reigned. True silence, that is, because it’s very easy for The River Made No Sound to filter into the background of whatever else it is that you’re doing at the moment.

But that’s the secret behind Pan-American’s mastery. At first listen, it’s easy to dismiss this release (the most minimal and restrained of Pan-American’s albums) as mere background noise. And much of it is seemingly random at first, a mish-mash of static washes, ambient drones, sparse Rhodes piano melodies, and various dub-influenced clicks and clacks. It’s a relatively small sound palette. But Nelson knows how to take his time and ply his wares, especially on the gorgeous opener, “Plains.”

At only three-and-a-half minutes or so, it’s one of the album’s shorter tracks. However, the ghostly melody and glassy rhythms, combined with AM radio transmissions of someone’s dying breath, create a mood of eerie nostalgia. Given the song’s icy, distant mood, there’s a sense of personal tragedy and sadness. Personally, I’d love to see Nelson venture more into this vein of ambience, but the rest of the album moves into more rhythmic country.

But “rhythmic” is used in the most glacial sense of the word. “For a Running Dog“ ‘s foundation is an insistent electronic pulsing, like the dull throb of an arctic rave a couple hundred feet below the icecap. The pulse itself feels muted and nearly insubstantial. Slowly, ever so slowly, Nelson works in his subtle dronework, while the rhythm grows increasingly hypnotic. Elsewhere, Nelson’s use of ambient noise and field recordings, as on “Settled” or the album’s closer, “Right of Return,” creates a mood equally mind-altering.

It’s hard to pinpoint just what, exactly, these recordings are, since they’re often buried low in the mix. I’d guess a combination of traffic passing outside a storefront, random street conversations, and other urban glossolalia. Even if you could plainly identify the sources, that wouldn’t alleviate their odd effect. You’ll feel like you’ve stumbled onto an abandoned street and are hearing snippets of psychic echoes from those who walked there weeks, months, and even years ago.

It is interesting how detailed the individual tracks can be, where even the slightest hint of a Rhodes piano can carry a huge mood. Yet it’s easy to miss where one track ends and the next begins. Though once the room is silent, I find myself wondering how such a minimal release could have put so much color and detail into the past 54 minutes.

There’s no denying that Pan-American isn’t for everyone. With each release, it honestly seems like Nelson is determined to minimize his albums’ accessibility as deliberately as he minimizes his sound. But at the same, there’s very little to disturb you from the serene, if uneasy atmosphere. Compared to the ominous dub mixes of Pan-American’s debut, and even the stellar follow-up, The River Made No Sound feels much more grounded and consistent, though it doesn’t quite plumb the same depths as previous efforts (Low’s appearance on 360 Business/360 Bypass floors me every time). Depending on how you see such things, the uniformity of The River Made No Sound might be its greatest asset, or its biggest liability.