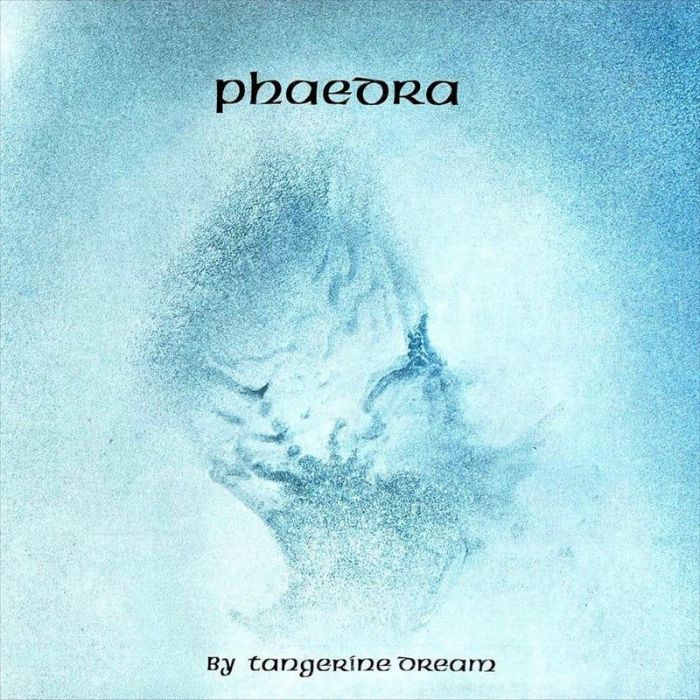

Phaedra by Tangerine Dream (Review)

One thing that bugs me is when people assume I’m some sort of music “know-it-all.” Oh sure, when it comes to krautrock, japanoise, and “kiwi rock,” I probably know more than your average joe. But the more you know, the more you realize you still have much yet to learn. Take, for example, electronic music. As with any genre, there are certain luminaries; Brian Eno, Roedelius, Cluster, Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream, Bill Laswell, Moebius, Terry Riley, etc. But you won’t find a copy of Music For Airports or Psychonavigation in my collection. You see, I can talk the talk, but that’s about it. Of all those artists, I only own albums by a few. And unfortunately, as great as The Man-Machine might be, it does little to really give you a sense of the genre’s growth.

Now, Phaedra is probably as a good a place as any to start if you want to start delving into the history of electronic music. And, I’m certain that when this was released in 1974, it was quite revolutionary. But I think that’s part of the problem of going back to older, influential releases; you listen to them through the lens of what you already know, and oftentimes, what you hear can sound clichéd and stereotypical. When I listen to “Phaedra” or “Mysterious Semblance at the Strand of Nightmares,” those synth washes, alien soundscapes, and atmospheric rhythms remind me of Robert Rich, Vidna Obmana, and Steve Roach. Shouldn’t it be vice-versa?

There are parts of Phaedra that are stunningly beautiful. If the opening moments of “Mysterious Semblance at the Strand of Nightmares” isn’t the dictionary definition of “ambient” music, I don’t know what is. But oftentimes, it feels like Tangerine Dream indulges their experimental side a bit much. “Mysterious Semblance at the Strand of Nightmares” starts off peacefully enough, but as it progresses from new age symphony to something more baroque, it loses its cohesion. Eventually, it dissolves into a mass of squiggly noises, modulations, and analog gurglings. That, or the tape it was recorded on began to unravel during the sessions. At first, it’s interesting, but soon, it becomes trying, especially since it obscures the song’s more beautiful elements.

Despite the title track’s supposed position as one of electronic music’s vanguard compositions, I find the album’s last two tracks the most captivating. “Movements of a Visionary” comes pretty darn close to living up to its title, but you have to be patient. At first, it sounds like Tangerine Dream still has too much knob-twiddling left in their system from the previous track. But this soon gives way to something resembling Steve Reich’s Drumming, if composed for PVC tubing, combined with cathedral-esque organs and haunting noises. But it’s really not possible to appreciate the piece’s depth unless you’re listening to it through headphones. Only then do you get a sense of the composition’s immense dimensions.

And with “Sequent C,’ ” the album closes on a calm, reflective note. Airy, vaguely Oriental melodies evoke scenes of ancient ceremonies carried out in mist-enshrouded pagodas, à la Robert Rich’s Propagation. Again, there’s a sense of immensity, or at least the promise of it, what with the track’s seemingly abrupt ending.

It should be noted that, despite the album’s analog origins, it has aged rather well. At times, the sounds are a little rough, and I’m sure that audiophiles might wince at some of the imperfections here and there. But on my $20 pair of headphones, those little imperfections enhance the humanity of what would otherwise be a stale, faceless electronic album.