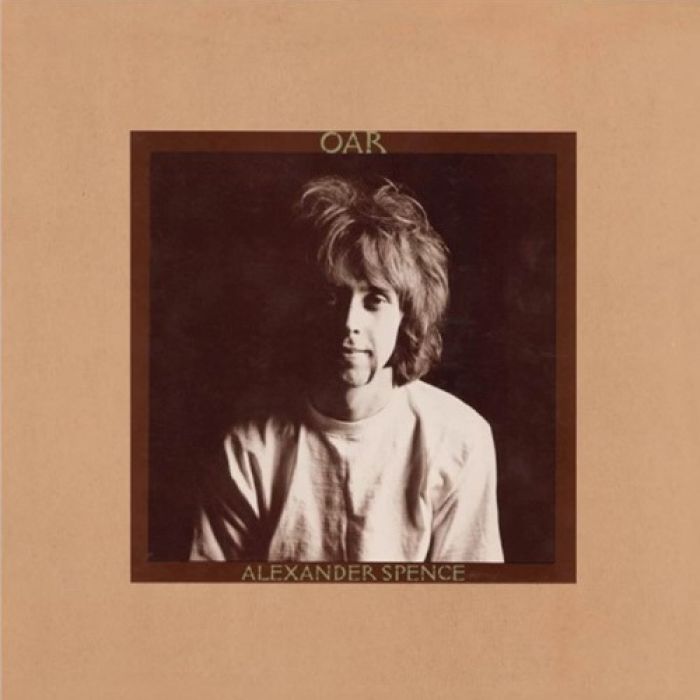

Oar by Skip Spence (Review)

Christmastime, 1968. Alexander Spence records the definitive psyche/folk album Oar at Columbia Studios in Nashville, Tennessee. The album is so woefully received, it reportedly sells a meager 700 copies. Alexander Spence soon disappears into the rugged terrain of the California Mental Health System, a paranoid schizophrenic and acid casualty. Just six months prior, Spence had attacked his New York hotel room with a fire axe. He then went into the studio and threatened his bandmates in Moby Grape. Producer David Rubinson had to physically restrain him, detaining him until Spence was taken away to New York’s famed Bellevue Mental Hospital. Spence was subsequently released into Rubinson’s care and, with a motorcycle and a small budget, Spence rode down to Nashville to record his only solo album — the harrowing Oar.

Oar is a spectacular achievement of truth and beauty, an example of raw emotion reduced to its purest form. There are sounds of past and future ghosts on the album; sounds never heard before or since. Spence delivers his songs in a rasp that sounds as if he has the scorched ground of a desert in his mouth — cutting high and tight in a strange squeal on the apocalyptic “War And Peace” and slowly dying to a low croaking murmur on the crippling “Weighted Down (Prison Song).” He never strays too far from the dusty early American influences of blues and folk, except with the mind-bending space rock of the album’s closer “Grey/Afro.” However, instead of staying strictly within the traditional bounds of these genres, he imbues them with gorgeously cracked, fragile guitar lines, off-time drums, rusty-stringed bass, and the beautiful noise that comes from recording on a primitive tape machine.

Oar was conceived, written, produced, arranged, and performed by Spence alone and upon listening to it you realize just how close you are to the heart of darkness; it was the last time that music got that close. The album was released the same year as Captain Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica, but is much more focused and absolute, never getting lost in a haze of incendiary esoterica. Oar has the mark of a fecund and warped mind, filled with stark images of countryside beauties and the untold horrors of madness. It is the sound of a mind letting go, a man being alienated. Spence’s Oar is the last gasp before a long painful death, the peace before a particularly strange and lonely war.

It’s essential to listen to the album from beginning to end, from the rambling grace of “Little Hands” to the warped rumbling of “Grey/Afro.” Spence’s songs jump from the biblical “Books Of Moses” to the playfully sexual “Lawrence Of Euphoria” with an aplomb that would shock Leonard Cohen. The album is filled with subtle word play which manifests itself in the chorus of “Weighted Down”: “Weighted down by possessions/Weighted down by the gun/Waitin’ down by the river/For you to come.” “Weighted Down” is so full of grief that Spence has trouble getting the song out. His voice is slowed down creating an effect which is essential to the song: a folksy prison anthem about hopes, dreams, women, and freedom not unlike Leadbelly’s own prison anthem, “Goodnight Irene.”

As a guitarist, Spence is mostly intuitive and almost says more with the instrument than he does with his words. The truly frightening and magnificent aspect of “War And Peace” is his solo — untouchable, shambling uncontrollably into the song like the bright light of burning jungle floors, the sound of bullets, steel, gulf heat, and incinerated hopes… the sound of the dead and the dying. The track that ends the album is the impenetrable psyche classic “Grey/Afro,” essentially a low rumbling effected bass rambling alongside Spence’s ghostly vocals and strange out of time ethereal drums. “Grey/Afro” does much to tie the album together — it’s filled with an almost religious purity, a chant within a chant. It is the most disarming track on the album, an antidote to the greed-induced guile of “psychedelic” bands like Pink Floyd.

It is difficult to compare Spence to other musicians, whether from his own generation or from generations that came before and after. Some may draw a comparison to Syd Barrett and in a way it seems appropriate. However, the truth is Barrett didn’t seem to have seen the same kind of hell that Spence had, or if he did he doesn’t show us like Spence does. Spence reveals terrifying things in stark and living detail, where Barrett shows us the playland in his head filled with ice cream, LSD, gnomes, and other jolly things.

One could also say Spence’s music is reminiscent of Charley Patton, Son House, or Woody Guthrie, but the spirit and atmosphere of Oar is very different. Spence was a rock star, a vet of San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury scene, whereas artists like Charley Patton and Son House struggled with the harsh cruelties of our backward society. Woody Guthrie and other early folk artists were dealing with the depression, World War II, and a very different post-war America.

Instead of expressing frustration with society and the oppressiveness of a changing America, Spence was instead dealing with his own personal demons. His mind was deteriorating, being eaten away by acid and other afflictions. The sound on Oar is devastating — its primitiveness is a byproduct of its guileless reality and the aesthetics that make it perfect are derived from his madness. Spence’s music comes not from societal ills but instead from the labyrinths of a man’s crumbling mind.

I believe Oar should be considered an essential American recording. It’s not about genre, technique, or songwriting. It’s about capturing the moment where a person hits bottom, like Alex Chilton’s attempt at a third Big Star album, or Blood on the Tracks, or Tonight’s the Night, albums that are harrowing and painful. Spence documents this moment with an intensity that can only be described as terrifying. It’s an unforgettable and traumatic experience listening to Oar — it must have been that much worse to be the one who recorded it.

Written by Bryan Price.