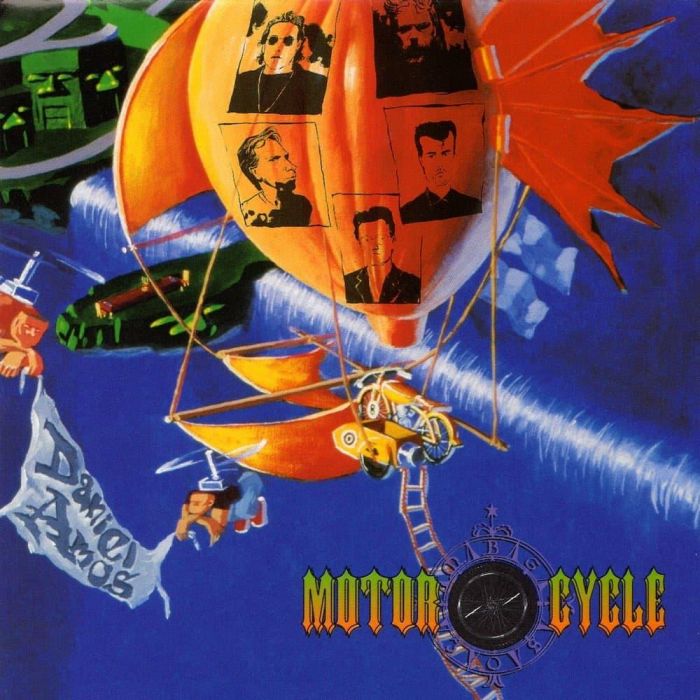

MotorCycle by Daniel Amos (Review)

As I was discovering indie/alternative Christian music in the early-to-mid ’90s, one name kept appearing in the production credits of albums from many of my new favorite bands (e.g., Mortal, Saviour Machine, Scaterd Few): Terry Taylor. This one man had left his fingerprints on music across a wide range of genres, from industrial and gothic metal to whatever Sin Disease is, which left me curious why such varied artists were working with the guy.

Working backward from there eventually led me to Terry Taylor’s most famous and long-running project, Daniel Amos. Emerging out of the Jesus Music movement in mid ’70s Southern California, Daniel Amos has been a rather hard outfit to pin down throughout the decades. They’ve delved into countrified rock (1976’s self-titled debut), new wave (1983’s Doppelgänger, 1984’s Fearful Symmetry), and in the case of 1993’s MotorCycle, psychedelic pop that hearkened to both latter day Beatles and the exquisite arrangements of Brian Wilson.

MotorCycle is an album that rewards intentional, repeated listens. The album’s fourteen songs are dense and excessive — in the best possible sense of those words. They practically burst at the seams with ideas and flourishes. Exotic psychedelia graces “Banquet at the World’s End” while “Traps, Ensnares” pairs sitar drones with, of all things, saloon piano riffs. The band’s triple guitar attack (Taylor, Jerry Chamberlain, Greg Flesch) adopts a dreamy, surf-like tone on “Hole in the World” while “Wise Acres” packs about a half-dozen guitar solos into its denouement.

Unpacking these layers and hearing the myriad of surprising choices that Daniel Amos made — and how well Taylor et al. made all of those choices work — is all part of the joy of listening to MotorCycle.

Much of the album’s mercurial nature can be chalked up to Taylor’s songwriting, which is best described as skewed. (Again, in the best possible sense of the word.) There are moments on MotorCycle when Taylor’s playfully twisted lyrics make him seem like a Weird Al-esque court jester. How else to make sense of lyrics like these from “Traps, Ensnares”?

Mr. Spoke speaks, deadly nightshade in his brainpan

Mock aliens breed silent blond zeros of fresh young flesh

Ignore the ghosts of books, they’re getting plastered in Paris

Della wears Tupperware, and Major-Domo’s body politicking in Limo Land

Harry Fiasco is gulping down his moral fiber

And casts his hard shadow while wearing

Those slippery soft supple slippers

And then there’s “Wise Acres,” with its gentle skewering of evangelical Christian sub-cultures:

They’re gonna put a fence ’round Wise Acres

And in the end, they’ll tear down Wise Acres

The truth would set them free but no one there can see

The greatest enemy is the exclusivity

But you’ll eventually find — though it might take a few listens — that something else is always going on beneath the cheeky lyrics and clever wordplay.

“Buffalo Hills” and “Noelle” both seem ridiculous at first, even cloying. The former employs extended baseball metaphors while the latter includes lyrics like “She gets her just desserts ’cause the sky is in the pie/She wants her cake, she eats that, too, as the meringue clouds roll by.” But a closer listen to both songs, which were written for Taylor’s kids, reveal them as heartfelt odes to childhood innocence. When Taylor sings “I’ve prayed her into a dream where hate can’t break the spell” on “Noelle,” he taps into a desire that every parent feels at the deepest, most primal level.

Taylor’s lyrics are also ridiculously literate, packed with references to Charles Bukowski, the Bible, C.S. Lewis, and most especially, theologian and author Frederick Buechner.

MotorCycle begins with “Banguet at the World’s End,” and its exotic sonic trappings are used by Taylor et al. to retell Jesus’ parable of the wedding banquet. When the beautiful people of the world can’t be bothered to leave behind their worldly pursuits, the door’s left open for the dregs and outcasts of society, who party the night away “in their sleazy clothes and orthopedic shoes.” (Taylor’s decision to include “mongoloid” — a slur for people with Down syndrome — on the list of outcasts might raise some eyebrows, though. On the one hand, his intent seems clear, given how people with the disorder are often treated by society. On the other hand, it’s still a slur, so yikes.)

But for me, the album’s highlight has always been “Hole in the World,” a gorgeous and haunting ballad about Christ’s Second Coming and the saints’ entry into Heaven. Taylor’s evocative lyrics draw heavily from Frederick Buechner’s The Alphabet of Grace and Whistling in the Dark as he sings:

Hole in the world

Here every tongue cries “Christ is risen“

Hole in the world

I see old enemies embracing

Moonlight falling on the blistered glass

Someone whispers, “Here at last“

That’s when I saw Your shadow pass

And:

My heart is aching, and my legs are broken

Waiting for the hand in the dark

The table is set, and the door is open

Inside, outside

Though I’ve been a Christian since childhood, I’ve often struggled with how to think of Heaven. But artists like Taylor, and songs like “Hole in the World,” help me imagine the unimaginable. It’s a song that I still find both inspiring and comforting, even after all these years.

As I’ve written before, one of my goals with Opus is to shine a light on Christian music that has long-flown under the radar. I don’t necessarily expect non-Christians to know of this music (though they should because it’s great), but I do think it’s a real shame that Christians don’t know more about the wealth of music created by their brothers and sisters, simply because it lies outside the bounds of, say, CCM. With its bizarre arrangements and oblique lyrics, Daniel Amos’ MotorCycle certainly doesn’t fit easily within the lines of “normal” Christian music, but that does nothing to diminish its status as an artistic and spiritual gem.