For years now, folks have been wondering what’s going on with Studio Ghibli — concerns that are no doubt more poignant following the death of Isao Takahata earlier this year. The acclaimed and beloved anime studio had even announced a “brief pause” back in 2014 following Hayao Miyazaki’s retirement (though Miyazaki eventually came out of retirement to work on a new film titled How Do You Live?).

Whatever Studio Ghibli’s ultimate fate — and Lord willing, they’ll be around for many years to come — it looks like the newly formed Studio Ponoc is more than willing to carry the torch, if their debut feature Mary and the Witch’s Flower is any indication, that is.

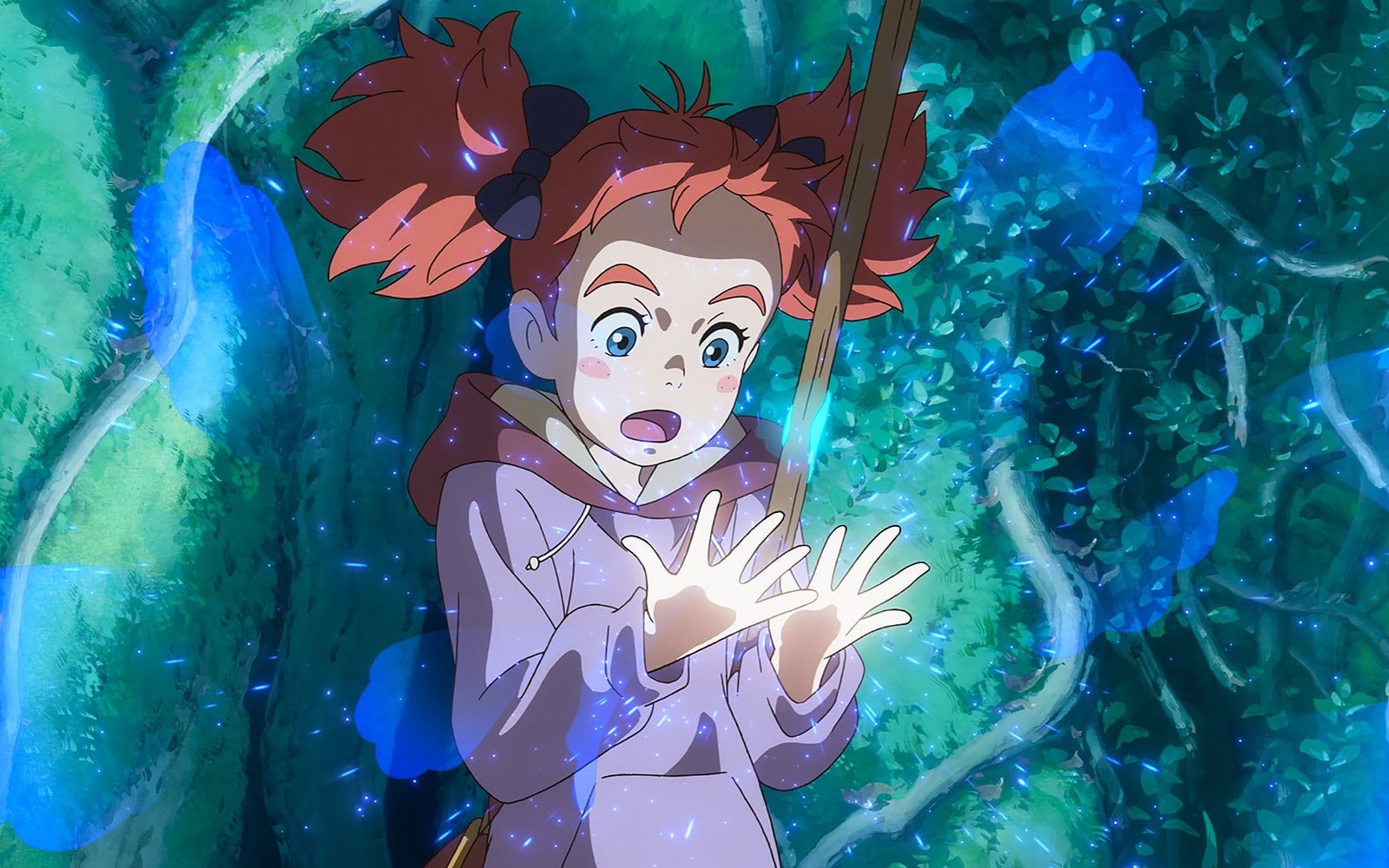

Directed by Hiromasa Yonebayashi (who previously directed The Secret World of Arrietty and When Marnie Was There for Studio Ghibli) and adapted from Mary Stewart’s The Little Broomstick, Mary and the Witch’s Flower could easily be mistaken for a classic Studio Ghibli film. It certainly ticks all of the boxes on paper:

- A feisty, strong-willed-yet-empathetic young girl for a protagonist? Check.

- Otherworldly whimsy with undercurrents of darkness? Check.

- Gorgeous European countryside as the backdrop? Check.

- A lovely musical score? Check.

- Gorgeously animated scenes, including several flying sequences? Check.

- A gentle, unassuming storyline that also contains a clear moral message about the abuse of power and the dangers of ignoring the natural order? Check.

Even the character designs look like they came from Hayao Miyazaki’s pen. On the one hand, it’s tempting to ask, given how well Studio Ponoc replicates the Studio Ghibli formula, what’s the point of watching Mary and the Witch’s Flower instead of a classic Ghibli title like Kiki’s Delivery Service or Spirited Away?

On the other hand, when you have a formula that’s as time-tested and delightful as Studio Ghibli’s, then any well-done iteration of it feels like a gift — and make no mistake, Mary and the Witch’s Flower is well-done. As the young Mary Smith, who is bored being stuck at her aunt’s rural home, finds herself suddenly falling into a world of magic — complete with elite schools for witches and warlocks and filled with strange magical creatures and experiments — the film offers viewers many visual wonders.

But two things ultimately stuck with me after watching the film.

First, its middle section, in which Mary is given magical powers by the titular flower and finds herself on the doorstep of the prestigious Endor College, is intended to be the most eye-popping portion. However, I actually found myself most drawn to the opening scenes. That’s when we’re introduced to Mary’s pastoral world, and it’s to Studio Ponoc’s credit that they make the bucolic, fog-shrouded British countryside seem as magical and mysterious as any magical school.

And second — and this might count as a spoiler, so consider yourself warned — I found it fascinating that a film about magic and witches actually turns out to be as much about the denial of magic as anything. While Mary and the Witch’s Flower might draw comparisons to the Harry Potter movies, Yonebayashi’s film is no simplistic celebration of spell-casting and its myriad wonders.

Rather, his entire movie revolves around two ideas: that magic is part of a natural order that should be respected and not abused, and that magic isn’t the higher good, but rather, something that can and should be denied without leaving one the poorer for their abnegation.

In hindsight, both of these points might do more to sustain Studio Ghibli’s legacy than simply copying its artistic and animation aesthetics. Mary and the Witch’s Flower reminds us that wonder and beauty can be found in the mundane, and that qualities like loyalty, sacrifice, and self-denial are as powerful as any magic spell — both qualities that have made Studio Ghibli films so endearing and important, and which make Mary and the Witch’s Flower a delightful movie in its own right.

For their own sake, I hope that Studio Ponoc will eventually emerge from the Ghibli shadow and carve their own path. But with Mary and the Witch’s Flower, they’ve definitely started off on the right foot.