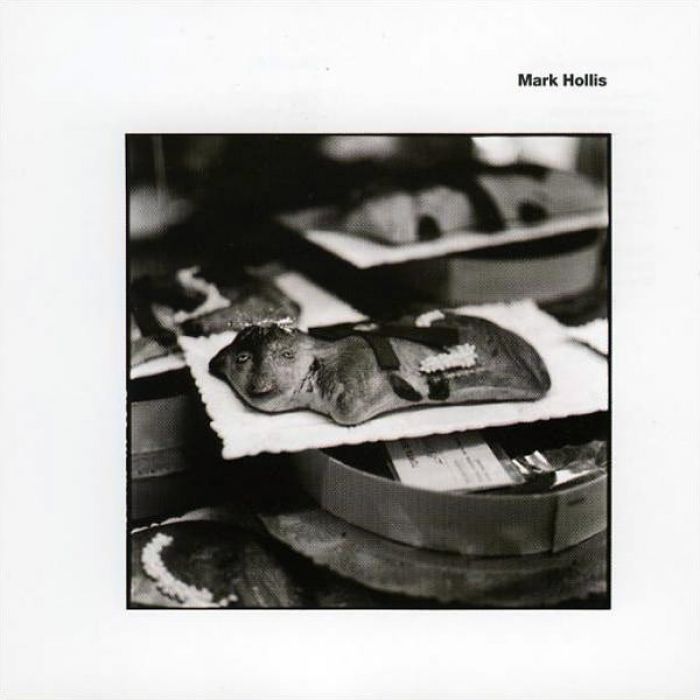

Mark Hollis by Mark Hollis (Review)

I’ve recently discovered a new quote that I love, that I feel sums up quite accurately my opinion on music, and why I’m drawn to so much music that many find slow, minimal, empty, even boring: “Before you play two notes learn how to play one note — and don’t play one note unless you’ve got a reason to play it.” Mark Hollis is the man who said it, and if anyone understands that Zen-like principle, who understands the immense significance that even a single note well-played can have, it’s him.

Formerly the frontman of Talk Talk, he led the band through a long transitional period. Getting their start as yet another synth-pop group in the early 80s, the band gradually moved towards a more rustic, poetic, and minimal sound on later albums such as Spirit of Eden and Laughing Stock. Eschewing synthesizers and danceable singles for sparse, jazz-like arrangements, obtuse lyrics, and a decidedly more subdued sound, Talk Talk’s music might have become less accessible, but it also became more rewarding, contemplative, and influential.

However, those albums were merely a precursors, it seems, to the music one finds on Hollis’ lone solo album, which was released seven years after Talk Talk’s demise.

To call his solo album “sparse” and “muted” would be gross understatements. At times, it seems like there’s nothing holding the album’s frayed threads — dusty acoustic guitar, slight piano and horn accompaniments, occasional bits of drum and other pieces of percussion — together except for Hollis’ plaintive voice. However, it’s the spaces between the sounds that ultimately define this record.

Not only do they cast a hushed, even reverent mood over the entire disc, but they allow each sound — guitar plucks, a piano notes, shivering harmonicas, chirping woodwinds, Hollis’ own voice — to take on meaning and impact. Each note feels deliberate, planned, and unwasted, but the unconventional song structures and instrumentation keep the music from feeling artificial. And the silences serves as pauses, short spaces in which the music breathes, lives, and gathers strength to move on to the next part.

The lyrics are often cryptic, to say the least. Hollis often seems less interested in what the words mean than what they sound like, how he can form and shape them and use their sounds as a vehicle to express pure emotion, not literal meanings and messages. As with the notes, they seem pared down, distilled to their bare essence so that nothing unnecessary gets in the way of the all-important mood.

That being said, Hollis’ lyrics aren’t merely used for the purpose of glossolalia. Take, for instance, the opening song, “The Colour of Spring” in which he intones “I’ve lived a life for wealth to bring/And yet I’ll gaze/The colour of spring/Immerse in that one moment/Left in love with everything.” One gets the sense of letting go, of forgoing the wealth and materialism of the world and opting for a simpler, plainer life rooted in love. Which, not surprisingly, parallels Hollis’ musical journey.

“Inside Looking Out” works as a simple lament, for lost youth, lost chances, and lost memories, etc. With an appropriately reflective piano melody meandering behind him, which is punctuated by graceful guitar filigrees, Hollis sings “Feel my skin Lord/Feel my luck tumbling down… Left no life no more/For me to shine.” And the album’s final track, the ironically-titled “A New Jerusalem,” is a stark ballad about the futility and horror of war.

“[T]he emptiness of war remains/One among five/But I’m dead to love/A pawn the same,” Hollis sings before finally pleading “Heaven burn me/Should I swear to fight once more.” Even though Hollis’ lyrics contain little detail, the psychic impact can be felt entirely through Hollis’ voice, the way he imbues each note with aching and suffering.

Mark Hollis can be, um, enjoyed purely as mood music, perfectly suited for lazy weekend afternoons, preferably rainy ones. (I just so happen to be finishing up this review on a Saturday afternoon, while it rains outside, which might explain why I began listening to this album in the first place, and subsequently wrote this review.) The moods contained within Hollis’ arrangements and vocals don’t reach out and grab the listener by any means, though some of the more unconventional moments might cause one to raise their eyebrow.

However, if one takes this album head on, moves beyond passively allowing it to settle in the background, and actually wrestles with it — how often do we actually wrestle with music for the purposes of discernment and discovery these days? — it becomes a transforming experience. One in which the slightest change, the slightest pause contains within it an ordinary album’s worth of emotion and meaning.