The King of Masks by Wu Tianming (Review)

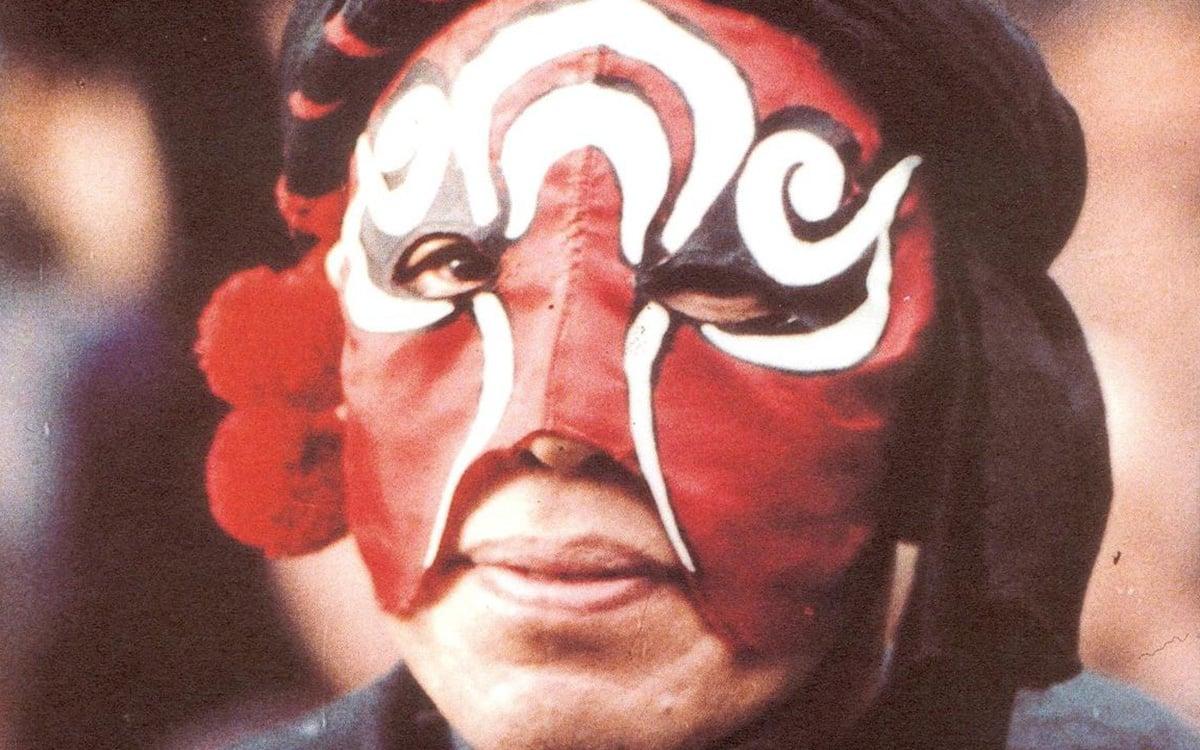

Bianlian Wang is an elderly street performer who tells stories with the masks he wears. His skill with masks is legendary, even gaining the admiration of the most famous opera performer in the land. Unfortunately, the King has no heir to pass on his craft to; when he dies, his art dies as well. To ensure his craft lives on, he purchases a child named Gou Wa on the black market. The only problem? Gou Wa turns out to be a girl.

The King of Masks does touch on many powerful, provocative issues. But in the process of exploring these issues, the movie left me strangely cold. It seems odd, because everything about the movie prepares one for a deeply moving, emotional story. Indeed, based upon the response I had to the trailer, I was sure I wouldn’t be able to make it through the movie without reaching for a tissue. But by the movie’s end, I wandered where that response had gone.

Perhaps it’s because the ending is never really in doubt; even in the movie’s darker moments, there’s no doubt that things are going to end on a positive note. I’m not saying that I wanted a tragedy, but even when Wang is wasting away in a prison after being charged with kidnapping, I couldn’t bring myself to feel any empathy.

When the movie tries to ramp up the melodrama, as in Wa’s last sacrifice for Wang’s freedom, it feels heavy-handed and desperate. And that immediately sets off some alarms. I don’t mind movies that are emotional and moving, but when they pile on the melodrama, well… suffice to say, I ended up watching The King of Masks with my forcefields up.

I know all of this makes me sound like a heartless bastard. I’d be lying if I said there weren’t any beautiful moments in the movie. Xu Zhu and Renying Zhou do a stellar job as Wang and Gou Wa, respectively. Zhu portrays Wang as a man who has had more than his fair share of suffering, but is still looking for a chance to share his skills and life with his family. When Wang finds the child that he thinks will be his true heir, his sense of joy is overwhelming.

A movie with a child as one of its protagonists sinks or swims with that role, and Zhou movingly shows Wa’s love and dedication. One scene that sticks out in my mind is when Wa is first rejected when Wang finds out her gender. Wa throws herself at Wang, desperate not to be left behind. As Wang leaves on his boat, Wa trails behind, pitifully crying out “Grandpa.” It’s a scene that could make the hardest heart melt.

But that kind of response overlooks the movie’s other side, which looks at the social traditions and structure of 1930s-era China. It’s this area that I found most interesting, because it provided a fascinating background for the emotional elements of story. Unfortunately, Wu only delves into this as much as is necessary, giving the viewer only a barebones look at the movie’s world. There are few scenes where this sense of tension are really palpable — such as when Wang is confronted by a group of soldiers — but they’re few and far between.

As such, you don’t really get the feeling that Wa is trying to go against age-old traditions when she tries to be Wang’s student. Rather, the movie comes dangerously close to portraying Wang as nothing more than a crotchety old man dealing with a stubborn little girl. And sooner or later, you know his heart is going to melt. Perhaps if that feeling of what Wa was doing had been more fully realized, the emotional impact of what Wang and Wa finally accomplish together would’ve been greater. It’s a solid movie, and not without any merit; in fact, it probably stacks up quite well to most dramas you’ll be able to find. But I was expecting so much more.