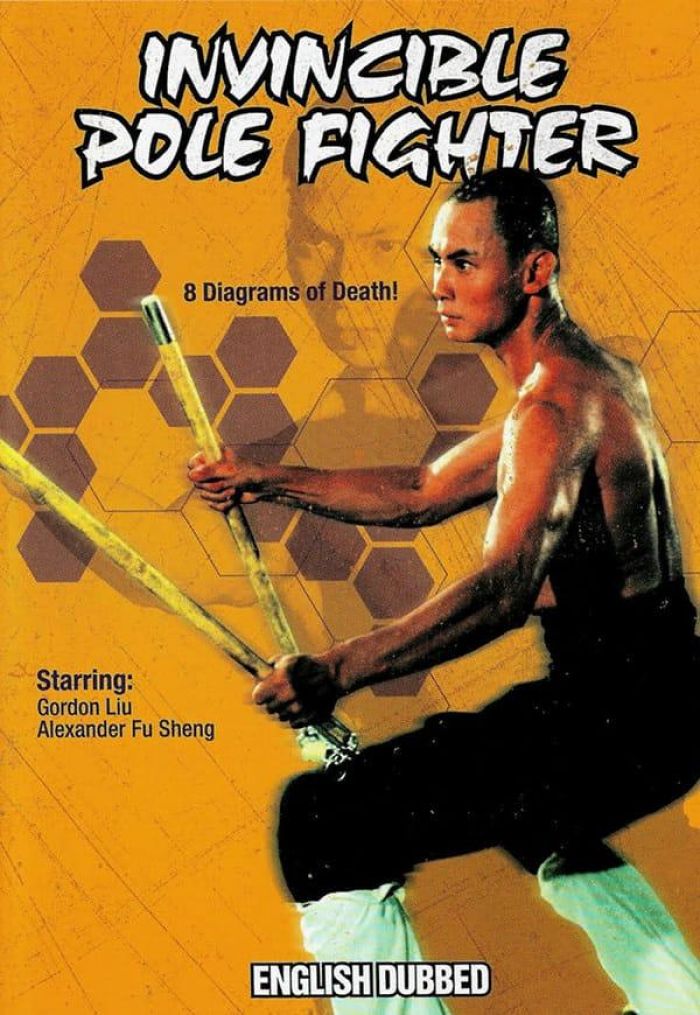

Invincible Pole Fighter by Lau Kar-Leung (Review)

I’m not surprised that most people don’t take kung fu movies seriously. After all, most people’s experience comes from “Kung Fu Theatre” or the countless parodies that you see from time to time. And so they associate kung fu movies with stilted dialog, melodramatic overacting, and physical feats that border on comical. I’d love to say that Invincible Pole Fighter is the movie that will change those people’s minds, but it’s not; in its dubbed, fullscreen version, it fits into all of above stereotypes. But there’s something tragic and disturbingly violent that keeps this from being just another chopsocky flick.

The Yang family is widely known for their loyalty to the Emperor. However, their name is disgraced when they are double-crossed by the rival Pan Mei, their family destroyed and branded as traitors by the real traitor. Only two brothers survive, Yang #5 (Liu) and Yang #6 (Sheng). #6 is driven mad by the brutality he’s witnessed. #5 escapes the battlefield, but is chased by the Mongols with whom Pan Mei has joined forces.

Eventually, he comes to a Buddhist temple and decides to become a monk. However, the monks see that he is a still a violent man bent on avenging his family’s honor, and refuse him entry. The brother stubbornly insists, and eventually resorts to violence to gain entry. This sets up the movie’s most interesting facet, as #5 struggles to reconcile his life as a monk with his life as a soldier.

#5 proves to be the temple’s best fighter, but is not allowed to practice with any of the other monks because of his skills. However, this isolation just drives his talents and increases his anger. No matter how much he tries to control his rage, it’s never enough. The monks constantly ask him to leave, but he violently refuses, believing this is the only way to improve his life. However, even the monks display a bit of hypocrisy. They claim that it’s unimportant who or what a man was before he comes to a temple, but they refuse to accept him and help him.

The only monk who reaches out to #5 journeys to the Yangs to bring them news of their lost son. However he is captured before he can return, and kills himself before revealing anything to the Mongols. But before his death, he reveals to the Yangs where #5 is located, and the eldest Yang daughter sets out to find her brother. However, Mei’s forces soon capture her. News reaches the temple, and #5 sets out to rescue his sister and finally avenge his family’s honor.

By now, it’s evident that #5 cannot be saved from his true nature. Although he had started to learn control and discipline in the monastery, the news of his sister’s capture drives him back to the life of a soldier he had tried to hard to forsake. This leads to the movie’s huge finale, as #5 and his sister take on the Mongol hordes with nothing but a couple of bamboo staffs. Although the film is fairly violent and dark, that mood is doubled in the final fight, as people are impaled, stabbed, get their teeth pulled out, and are thrown headfirst through coffins.

The movie does have its flaws; compared to the slick productions that many HK films are these days, it does look pretty amateurish, and it certainly can get tedious if you’re looking for some instant kung fu action. The set designs are pretty basic, the fight choreography — which is butchered at times by the movie’s fullscreen aspect — is nothing really flashy, with the exception of a handful of scenes (like the aforementioned finale), and the dialog is certainly lacking in poetic flair.

It’s easy to see how this movie might slip under most kung fu fans’ radar. It’s a fairly bleak film, with no humor to lighten the mood at any time (if you want that, get something by Jackie Chan); I doubt even the dubbing, that punchline of all kung fu cinema jokes, can’t be played for yucks. It’s all drama and conflict, and it does lend itself to fairly melodramatic scenes (especially those involving #6 and his insanity, which are played to the hilt by Fu Sheng). Still, the central conflict, that of a man struggling between the two sides of his nature, unable to reconcile his violence and rage with the desire to be free of such things, shouldn’t be ignored.