He Was a Woman by David Hurn (Review)

I’ll get to David Hurn’s record in a minute. First I want to talk about The Smiths, which only makes sense to me at this point. The Smiths wore their country influences like any of the other fan badges on their collective black jean jacket. And true enough, twang is many things to many people. For Johnny and the boys, it was all about rockabilly, Elvis, and pompadours. Musically, this tendency surfaced perhaps best on the underrated Meat Is Murder.

Tracks like “Rusholme Ruffians” and “Nowhere Fast” rode the mechanical bull with such grace and charisma that fey boys with daffodils were none the wiser that they were actually moping-out to country music. That’s Morrissey’s doing. He could have given a shit, really. I can’t hear him saying, “Oh, we’re doing a country song? I guess I’ll have to kick something up about hard livin’ and hard lovin’.” Morrissey was Morrissey was Morrissey.

English moper David Hurn’s He Was a Woman can best be described as The Smiths doing a different kind of country — more the kind of mellow country-folk we’re accustomed to hearing nowadays (especially with the whole Alt-country phenomenon). I guess The Lilac Time’s Looking for a Day in the Night would be a good reference point. Hurn also incorporates some functional jazz-like elements into his music, giving himself kind of a Tindersticks (or God forbid Cousteau), or maybe even John Martyn angle at times.

Although the occasional string arrangement enters the fray (Warning! Obligatory Yet Inaccurate Nick Drake Comparison Alert!), his primary weapon is the almighty acoustic guitar, accompanied with light touches of piano, distinctly sweet pedal steel guitar, and of course, bass and drums. Does it ever really sound like The Smiths? No. It’s good, but more like the Sundays, who were just a watered-down version of The Smiths. But Hurn himself is an interesting lyricist, albeit simpler than Morrissey, but compelling and with sensitive gifts nonetheless (and a pretty decent singer of the monotone variety too!)

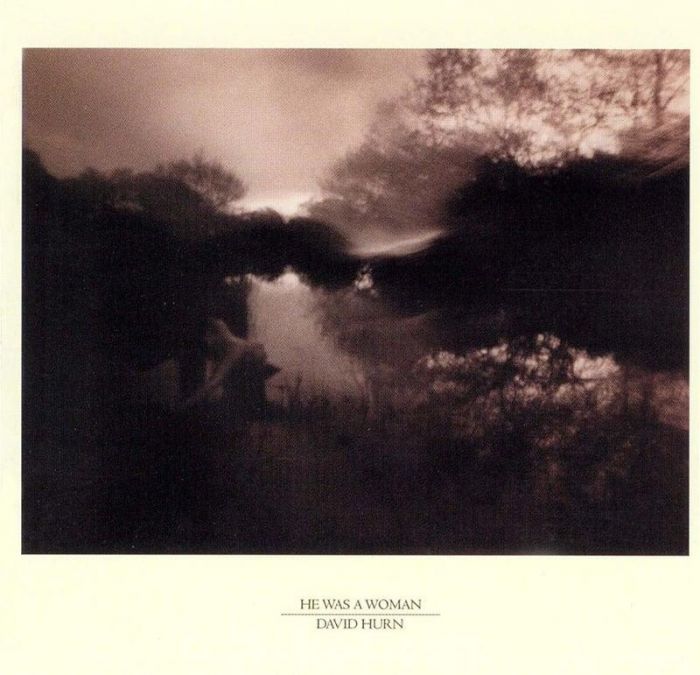

A glance at the cover of this disc confirms all of these suspicions: a sepia tone photo of obscured trees being reflected on water on a plain antique white sleeve with small type beneath the photo reading “He Was a Woman — David Hurn.” If I am not painting an accurate enough picture, I’ll just come out and say it; this looks a lot like Joy Division’s Closer. Tracks listed on the back fall in small print, with a division indicating album sides. Clearly, Hurn is trying to conjure the age of the album, or more specifically 1982 – 3.

And as for that title, He Was a Woman, Hurn perhaps is borrowing what was one of the most signifying traits of Morrissey’s style: the asexual humanization (albeit sometimes misanthropic in Morrissey’s case) of his characters. Think, for example, of “Sheila Take a Bow,” where Morrissey forgets that he’s the boy and she’s the girl. Morrissey’s ability to desexualize and humanize adult relationships was possibly borne out of his own identity issues. For the case of David Hurn, this may be only half as true or half as severe, and that may make him appealing to some people who just can’t take Morrissey’s personality for this reason.

The lowest common denominator of the album is a sterile brand of pastoral country folk that weaves through every song at some point, like a turn-of-the-century wagon wheel creeping down a grassy lane. Case in point, the opening title track, whose spectral cello and samples of wind blowing create a cold cold feeling I’m glad to shake by track two. The excellent “Don’t Have to Live” is a melancholy yet uplifting Smiths-ian piece of quasi-Dixieland piano balladry, perhaps musically inspired by rollicking numbers like John Lennon’s “Oh Yoko” or Billy Bragg’s “Waiting For The Great Leap Forward.”

My breath gets a little lost listening to the sentimental cowboy junk of the pretentiously titled “Books, etc.” Hurn thinks, hands in pocket, “I don’t need to know if anything’s above me watching me cry my tears/Don’t a light showing me my fears.” He remembers to himself “I don’t need a ticket for a game/For a game that I don’t want to play anyway/I don’t need a light showing me my fears.”

Side One is then highlighted by the smoldering Tindersticks-ish “Nancy Put Yourself First For A Change.” “Nancy…” employs the immediate drama of horn and string arrangements, effectively putting some punch behind Hurn’s impassioned crooning. “We’ve both been here for far too long, serving the same kind of people,” he intones. “Anyone who tells you they know what the truth is/It usually means they just want your money.” If that doesn’t sound enough like Morrissey for you, just wait! You’ll hear recorded TV sets on not one, but two tracks on this album.

Side Two opens with “You Don’t Want To Know,” which lacks the spark of its obvious model (mid-period Billy Bragg), but is nonetheless enjoyable. Next up, “She Died Alone” is lighter and brighter than one would expect from a title so bleak. Hurn strums elegiacally, “And now you’ll die alone/Remembering the times you’d known/And the love you thought you could own/Written on her tombstone/She died alone.” The hits just keep on coming!

Anyone longing for the joyful butterscotch of The Sunday’s Harriet Wheeler needs to hear “No Love.” You could swear that Hurn learned how to write songs that make you feel like you have a crush on music straight from Johnny Marr. “Black Car” — the “Meat is Murder” of the album if we buy into that comparison — bogs with the same kind of faux-operatic drama and distortion that has given us trouble via everyone from Led Zeppelin to The Bitter Springs. The album closes with “Why Is a Good Thing Always Leaving,” a near return to form with the same kind of rain-smeared passion of “Nancy,” confirming for me the tone of the album and cementing the kind of tender moments I will always associate with David Hurn’s name.

Written by Jonathan Donaldson.