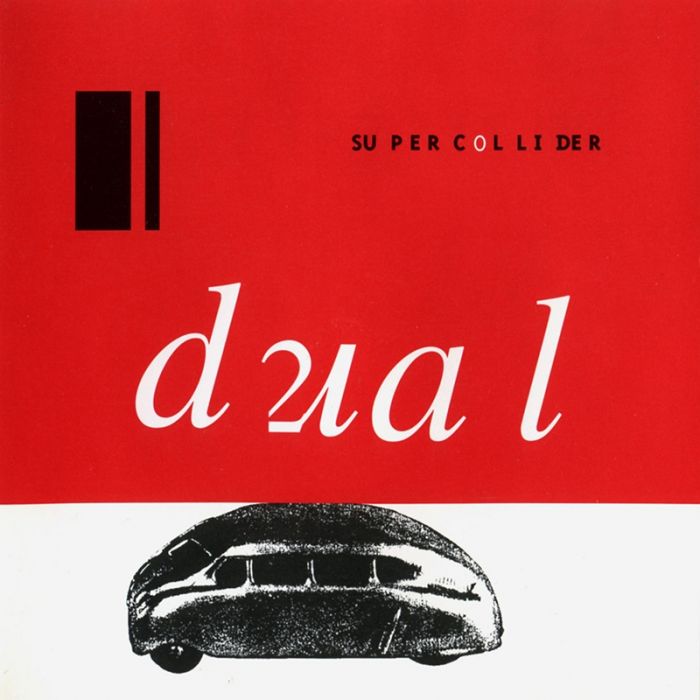

Dual by Supercollider (Review)

Supercollider’s modus operandi would probably get them lumped in the post-rock scene. But compared to many post-rock groups who try to create lush, spacious worlds and vistas with any amount of studio trickery, there’s something surprisingly raw and brutal about Supercollider’s music. Although many post-rock artists draw inspiration from the likes of minimalists such as Steve Reich, Supercollider’s music sounds like minimalism injected with a dose of punk, then reduced to its barest bones of rhythm and texture and left to bleach in the desert sun.

It’s very easy to break every song on Dual down to its barest essentials. A short melodic fragment, usually a metallic guitar scrape or chiming of some sort rings out and begins to loop back on itself. Then Phillip Haut fires out a rapid burst of drumming, consisting of nothing but a brittle high hat, a harsh snare, and a ride that sounds like a funeral bell. It’s not flashy at all; there are no pyrotechnics here. There’s simply a rhythm that serves either to drive the song into your psyche or pummel it to the ground. Occasionally, Michael Horton will let a strangled burst of feedback wail from his guitar, or will let it rumble around somewhere in the background. At its gentlest, it’s reminiscent of Seefeel, but more often than not, it sounds like a Mogwai-esque epic that just couldn’t build up enough steam to reach its climax.

And then there’s Horton’s voice. Like the music, it’s raw and stripped of any pretension. There’s no smooth polish to it, no dreamy quality to transcend the music. Someone described it as similar to Paul Buchanan (The Blue Nile), but Buchanan always sounds like he’s about to break down in tears at any moment. On the other hand, Horton’s voice smacks of desperation, and frequently cracks and fails to hold a note. But It’s this rawness in Horton’s voice that makes the music transcend above its mere rhythm and texture.

When Horton’s voice breaks while singing “I have no hope or teeth to bite” (“Hopeless”), it sounds like an alcoholic’s last cry for help. The imagery Horton uses is as raw as the music; sharp, brittle images of cracked walls and long asphalt roads. There’s no elaborate, poetic imagery to be found. And even when the lyrics get bizarre (“Who owns the jackhammer/Who fools the future/Who owns the copper eye” — “Superior”), the music doesn’t let them get away with it.

The album’s weaker moments are maddening. Some of the songs feel like they’re never going to evolve past the rhythm they’re mired in. And let’s face it; 10 songs based upon the same basic, ultra-sparse formula runs a little old if you’re not ready for it. But when you listen to something like “Hopeless,” the formula works so very well. The short sonic fragments sound like they could break at any moment; the simple structures the songs are built on always feel in danger of falling in on themselves. Meanwhile, Horton’s voice cracks and wails away in the distance, as if seeking solace from the barrenness of the music that surrounds it.