On Celestial Archive, Jay Tholen Finds Joy and Security in God’s Sovereignty (Review)

It’s been four years since Jay Tholen’s last album, 2013’s excellent The Low Drone of Earth. Instead of writing quirky, heartfelt music, he’d begun developing quirky, heartfelt video games such as the acclaimed Dropsy (where you play a twerking, hug-loving clown) and Hypnospace Outlaw (where you defend the internet of the future, which looks an awful lot like GeoCities).

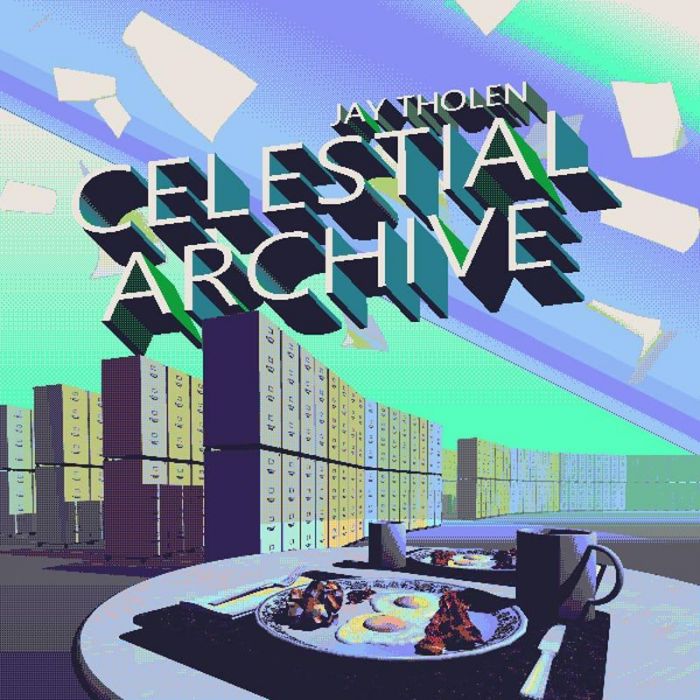

Music seemed to have been moved to Tholen’s backburner for the foreseeable future, so imagine my delight when he unexpectedly announced a new self-released album, Celestial Archive. Spoiler alert: Tholen’s latest is weird and goofy… and also delightful, deeply heartfelt, and idiosyncratic — which is pretty much what you’d expect and want from a Jay Tholen release.

It’s also one of the best worship albums I’ve heard in a long time.

Hearkening back to the spiritualized bizarreness of 2010’s Control Me and 2011’s Mud Pies or Bread and Wine?, Celestial Archive finds Tholen melding a dizzying array of trippy sounds (e.g., 8-bit video game music, ambient washes, vaporwave-y psychedelia, off-kilter electronic prog) with lyrics that contemplate marriage and family life (“Even Though”) and what it means to be an artist (“Onus Productivity Suite”). But one theme undergirds the entire album: Tholen’s amazement at God’s sovereignty.

They have nothing in common, musically, but one of my first thoughts upon listening to Celestial Archive is that it’s an interesting counterpoint to David Eugene Edwards’ Wovenhand, especially an album like Consider the Birds. Whereas Edwards finds God’s sovereignty to be a fearsome thing that leaves him both worshipful and discomfited, Tholen finds God’s sovereignty to be an endless source of joy and security — particularly within the context of his marriage.

The multi-movement “Celestial Archive of Ornately Authored Plans” finds Tholen contendedly musing “It’s hard to think when there’s so much suffering/That He mapped our lives through space and time instead of other things… It’s good to know that all you’ve been through/Was carefully arranged by a God who really loves you.”

“Even Though” finds Tholen making a laundry list of foibles and oddities that describe both himself (“Even though you’re sure to hear me whine/From the slightest pain every single time”) and his wife (“Even though you’re wrong about video games/Your abhorrence of coffee brings our family shame”). Nevertheless, he comes to a single conclusion: “After all He knew we’d be this way/He knew and He let us marry.”

This theme arguably reaches its apex in “He Wrote It All Down.” God’s sovereignty and foreknowledge — some of the most challenging aspects of Christian theology, regardless of the strength of your faith — are revealed, thanks to Tholen’s lyrics and swirling, bubbling electronic music, to ultimately be a source of security and confidence:

And when the world was made, the boundaries surveyed,

His brilliance displayed

He thought of you and ordered it so

You’d love me and I would love Him

And He would love us, too

It’s good to know it’s written somewhere, penned by holy hand

That note allowing me to love you

You’d one day love me and I’d love you

It’s good to know He wrote it all down

In some celestial notebook somewhere

Of course, Tholen being Tholen, he concludes the song with a heartfelt “I think that’s pretty cool!”

Christianity is an incarnated faith, one where heady theological concepts are of little good unless they — like the Savior Himself — actually enter into this world and do something. In 1 Corinthians, Paul the Apostle wrote that even “if I have prophetic powers, and understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have all faith… but have not love, I am nothing.” As Tholen muses about the sublime joys of marriage, he realizes a similar, and humbling truth: “Maybe through us He will ease somebody’s pain/We have no idea how we fit into what He has ordained.”

In other words, there’s a praxis to Tholen’s theological musings. All of the ways that God, in His sovereignty, has blessed Tholen are meant for something more than just personal comfort and pleasure. And so Celestial Archive ends with Tholen coming to a striking realization:

It’s a privilege to make things

Even though it won’t make me money

It’s amazing that you are hearing

What I’m writing, sounds I’m putting down

Could this be for you?

What I make can affect you

I don’t know who this stuff will reach so

What I make should be beneficial, good, and gentle

And never pull you down

Some might dismiss Tholen’s music as goofy or weird for weirdness’ sake, especially given Tholen’s love for surreal and muzak-y synthesizer sounds. But it’s not so easy to dismiss the humility in Tholen’s lyrics or the lack of pretense in his warbling vocals. Nor is it so easy to dismiss the gentle way in which Tholen’s music proves convicting.

In a world where art like music and video games (two of Tholen’s passions) is so easily commodified, rebooted, and focus group-ed to death — or used as a vehicle for narcissistic self-expression — stating that art should be about more than the artist’s ego, or that making something “beneficial, good, and gentle” is more important than money, is an act of true rebellion, not to mention worship.

At one point in the album, Tholen simply asks “Do I deserve to say any of this?” against a chillwave backdrop. Well, maybe “deserve” doesn’t have anything to do with it, at least as far as listeners are concerned (and hopefully more listeners will come). I think it’s just sovereign grace, pure and simple. I’m hard-pressed to think of another term that adequately describes the gift that is Celestial Archive.

To truly experience Celestial Archive in all its glory, be sure to check out the “Celestial Archive Multimedia Experience.”