Bathe in Black Light by Desiderii Marginis (Review)

Several years ago, a massive thunderstorm swept through Lincoln and knocked out power across the city. Having nothing else to do, and being good Midwesterners who’ve never met a storm we didn’t like, my wife and I decided to go for a leisurely drive through the rain-swept countryside.

Even after driving a few miles outside of Lincoln, the weather was still intense; black storm clouds laced with lightning filled the sky. At one point, we turned around and started heading back into town — but as it turned out, I wasn’t ready yet. I had a near-physical compulsion to turn the car around and drive even deeper into the storm. That probably wasn’t the wisest choice, but playing it safe and going home seemed wholly out of the question.

The storm was wild and untamed, the darkness vibrant with mystery. Driving down those Nebraska backroads, surrounded by still-darkening clouds, we felt tiny and insignificant — but ironically, more whole and alive than we had before. I suspect this thrill is akin to something that all enjoyers of the unknown feel, be they divers descending into the ocean depths, mountaineers ascending a treacherous peak, or scientists peering into the cosmic void.

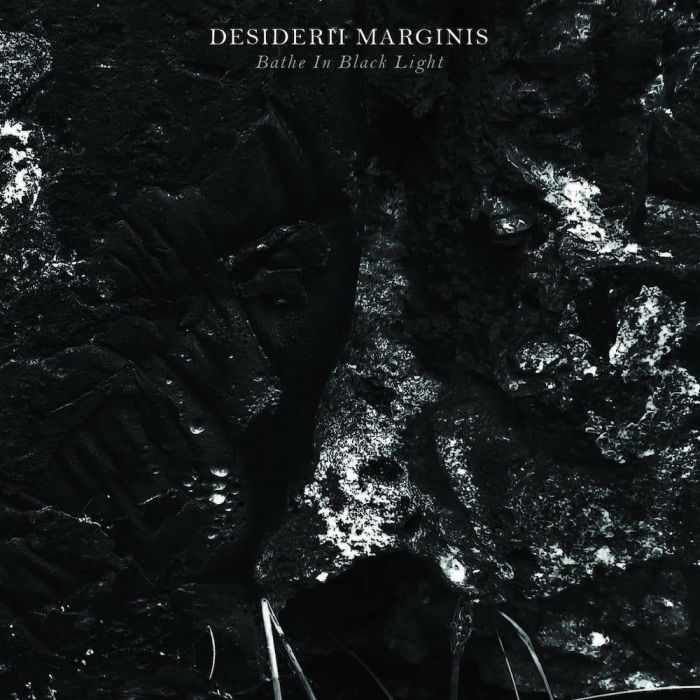

Bathe in Black Light, the twelfth full-length from Johan Levin’s long-running Desiderii Marginis project, feels like a sonic distillation of such encounters with darkness and the tantalizing sense of mystery and adventure that they represent. (Or as Levin puts it, the album is “[a]n ode to the night, the darkness that is not blindness, the intense tranquility and boundless inner wilderness.”)

The usual Desiderii Marginis elements are present — e.g., vast, desolate drones and melancholy synthesizer drift, industrial clangs and clanks, disembodied choirs and monastic chants, a surprising melodicism — and Bathe in Black Light finds them combined in sublime ways that balance adroitly on that too-narrow line between oppressive and otherworldly.

Listening to Bathe in Black Light, and particularly compositions like “Night Grasping at Day” and “Twilight,” is like standing high atop a windswept point and staring out across the stark and barren wilderness far below. A place blasted by time and the elements and dotted with ivy-covered ruins that were ancient even millennia ago — and all the more glorious for their decay. There’s a sense of loss and danger, but also, an urge to explore and experience. The album’s seven songs evoke a sense of desolation so deep and pervasive that it, strangely enough, becomes timeless and majestic — much like the fury of a storm or the precariousness of a mountain pass makes them irresistible.

No doubt some will listen to Bathe in Black Light and find it densely overwhelming — and little else. The songs will seem static and directionless, glacial in their pace. Levin’s ominous arrangements will stir little emotion other than distaste, perhaps even boredom. But for those who have ears to hear, Bathe in Black Light is dark ambience par excellence, and one of the finest albums to date from one of the genre’s most well-established and well-regarded figures.