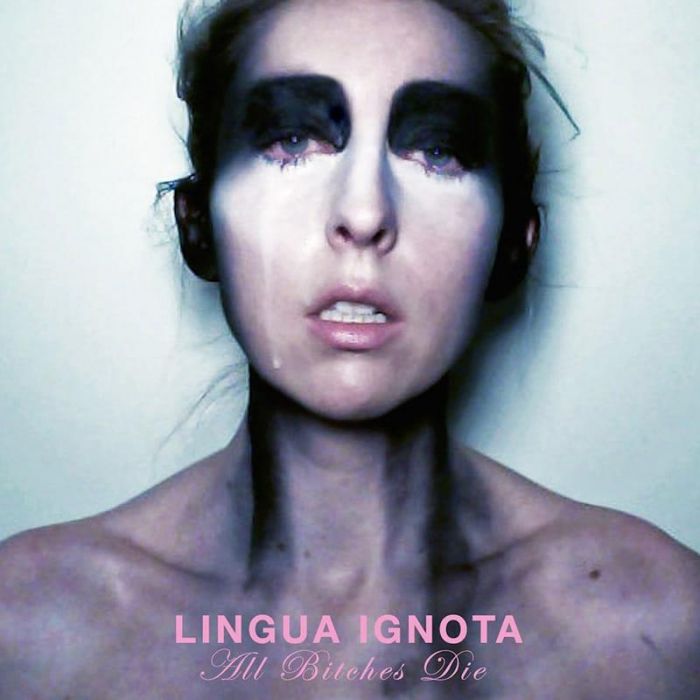

Lingua Ignota’s All Bitches Die Tackles Misogyny and Abuse with Brutal Electronic Music (Review)

Much of the music I listen to and review — be it ambient soundscapes, shoegazer pop, spaced out vaporwave, retro synthwave, etc. — can fade easily into the background (which is by no means a comment on its quality). But a couple of recent albums, though very different from each other musically, have placed similar exacting demands on my attention, and for good reason.

Earlier this year, Mount Eerie released A Crow Looked at Me, a heart-breaking album in which Phil Elverum mourns his wife’s death and contemplates life without her. And then a few weeks ago, I discovered the music of Kristin Hayter, a classically trained vocalist whose punishing electronic music tackles themes of domestic abuse and misogyny.

Hayter’s music — which is influenced by liturgical and sacred music and recorded under the Lingua Ignota moniker — draws heavily from her MFA thesis titled “Burn Everything Trust No One Kill Yourself.” Among other things, it features a 10,000-page document “composed exclusively of… lyrics, message board posts, and liner notes from subgenres of extreme music that mythologize misogyny, such as: black metal, hardcore, harsh noise, power electronics, grindcore, and with particular attention to pornogrind, a subset of grindcore with lyrical content that graphically details sexual violence.”

Not surprisingly, there’s very little that’s comfortable or comforting about Lingua Ignota’s latest album, the self-released All Bitches Die. Subsequently, it’s one of the most difficult albums I’ve heard so far this year, as well as one of the most compelling.

Hayter purposefully writes music that’s difficult for her to perform — as she describes it, “I intentionally situate the music in keys that are awkward for my voice so that I have to jump between my head and chest registers, climb up and down octaves, [and] move between… screaming and singing” — and the listener is spared none of that discomfort and distress.

“Woe to All (On the Day of My Wrath)” begins the album with maddening industrial clatter, power electronics, and Hayter’s distorted howls and wails. (Think Ben Frost remixing Mental Destruction, with some Diamanda Galás thrown in for good measure.) A reprieve seems to occur after several minutes; the noise is replaced by solemn piano and Hayter’s voice changes from unearthly howls to sweeping, operatic tones. However, her lyrics continue the onslaught as she weaves a story of domination, abuse, and guilt while employing apocalyptic imagery that could’ve come straight from Revelation:

My master pulled me from my bed

Ripped every curl from out my head

Held me down to strip me bare

Said “Hell is real, I’ll take you there“

Oh master, master, please be kind

Don’t leave me somewhere God won’t find

Don’t drag me to a sea of flame

From which I’ll never rise again

[…]

Where’er I walk, 10,000 flies precede me

Where’er I walk, 10,000 serpents follow at my feet

My tongue is an axe and a sword and a five-pointed dagger

With a single word every mountain shall crumble

Every tree shall fall

Every field shall be razed

Every crop shall rot

Every home shall be painted with blood

Every lung shall be flooded with bile

Hayter is a survivor of abuse herself, and has explained how her music is an attempt to work through, and even exorcise, her experiences. One would certainly expect such an attempt to be tinged with anger. However, there’s something almost biblical about the wrath channelled through these four songs.

“For I Am the Light (and Mine Is the Only Way Now)” finds Hayter at her most furious as she imagines a back-and-forth between a vengeful God and a violated supplicant seeking justice. The song seems almost blasphemous at times, but Hayter’s juxtaposition of thunderous organ and stark divine dictims (e.g., “Each breath you draw is Mine/Each fingertip is Mine… All things begin and end with Me”) with samples of a children’s choir and televangelists strikes me as a critique of our culture’s sanitized visions of God more so than of the Lord Himself.

As a culture, we’ve become very uncomfortable with the idea of an angry God. (This is true inside the Church as well as outside; just look at the ongoing debate surrounding penal substitutionary atonement.) We much prefer the idea of a kind, loving, and gracious God. By contrast, Hayter seems to find comfort in God’s wrath; only an angry, vengeful God can address the wrongs done to her and give her the justice she needs. (In this regard, she shares common ground with many of the Psalms.)

Subsequently, the aforementioned juxtaposition takes an additional twist in the song’s final moments. Even as the music crumbles around her in torrents of fiery noise and distortion, Hayter can be heard singing, calmly and serenely, the same children’s hymn (“All Things Bright and Beautiful”) that opened the song. God’s in His heaven, she has her justice, and all’s right with the world.

But for all of her music’s impenetrable sturm und drang, there’s a paradoxical desperation and vulnerability that can be glimpsed amidst the defiant screams and intimidating noise. When Hayter cries out “Lord God, frigid Father/I beg of you… intercede for me, console me with blood/That my woes be avenged one thousand-fold,” it’s chilling. And there are moments of conflicted beauty, such as the elegant piano strains that close out the dirge-like “All Bitches Die (Bitches All Die Here).” (That those strains are paired with Hayter mournfully intoning the title phrase only adds to the conflictedness.)

It may be tempting to write off All Bitches Die as “experimental” music or some sort of pretentious art project. Surface-wise, it certainly has all of the trappings. But the conviction that Hayter brings to bear in her music, as well as the visceral sense of pain and outrage that fills her songs, makes it difficult to dismiss the album out of hand. It’s certainly not going to be everyone’s cup of tea, nor is it trying to be — so if you can’t make it past the album’s first minute, I don’t blame you. But as far as I’m concerned, I’ve yet to hear anything so uncompromising this year — which gives All Bitches Die a stark beauty all its own.