After the Day Before by Attila Janisch (Review)

Just before After the Day Before began, director Attila Janisch (who was at the screening along with what looked to be some of the film’s cast) asked the audience to please be patient with the movie, assuring us that, even if the film didn’t make sense halfway through, it would all become clear in the end… “like life,” he said. However, I had easily figured out the film’s “twist” by the mid-point.

But looking back, “twist” feels too abrupt and sharp to describe what takes places in this slow, contemplative, and foreboding film. A slow, inexorable arc or spiral might be a more apt description. But whatever the case, it’s not the reveal, the sudden “ah ha!” moment at the end that makes this film enjoyable. Even correctly guessing the film’s twist well ahead of time didn’t deter me one bit from enjoying the film’s overwhelming sense of atmosphere, or from eagerly waiting to see how the twist would play out in the film’s final act.

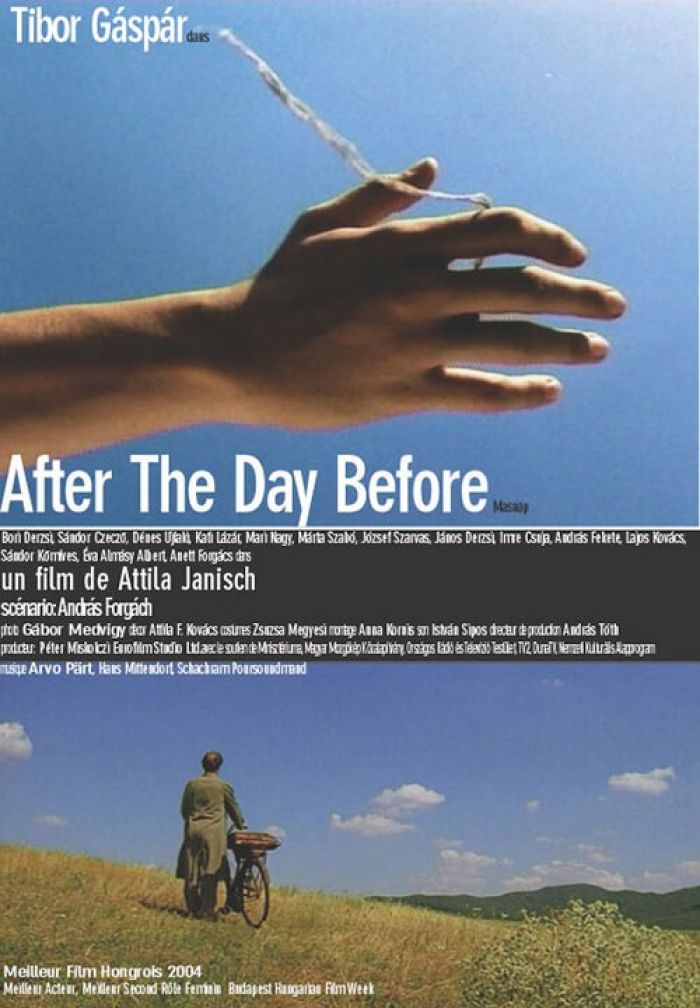

The film begins with a nameless photographer (Tibor Gáspár, who looks like a cross between William Hurt and John Lithgow) getting dropped off on the side of a country road in the middle of nowhere. From there, he makes his way on bicycle towards a rundown village (the driver who drops him off merely refers to it as “the settlement”), hoping to find some information about a house he’s just inherited. When he arrives, he finds that the villagers are less than helpful, if not downright surly. By the end of the first day, he’s already been insulted, mistaken for someone else, and asked by a young girl to kill her mother — all of which he takes in with a mixture of detachment and confusion.

As he travels through the strange-yet-familiar countryside, he meets more strange individuals: a man who curses loudly while chopping wood and his wife who wants protection for her and her girlfriend; a moody young man and the mysterious young woman he’s seeing, whom everyone in the settlement seems to despise; and a surly gentleman who rides around on his smoke-belching motorcycle, seeking to punish the young couple.

What’s even stranger is that the photographer somehow seems to have become unstuck in time (as might be implied by the film’s title). The film’s non-linear structure has him jumping back and forth in his journey. He stares out the window of an empty farmhouse, only to be gazing at some bizarre vignette unfolding outside his train window before he arrives. He arrives at the village, only to find himself still on the road there, and waking up from a nasty wreck to boot. He sees a young girl, only to learn that she has been murdered, an event that suddenly galvanizes the entire film, and which draws him in as he seeks to understand what’s going on and his involvement… all while trying to find his farmhouse.

At times, After the Day Before feels rather pretentious and interminable. But more often than not, it’s fairly enveloping, and not without a considerable amount of tension. Although the lush, sun-bathed Hungarian countryside looks gorgeous, courtesy of cinematographer Gabor Medvigy, I’ve never seen fields and pastures seem so ominous and foreboding. Much of that has to do with Istvan Sipos’ sound design, which is full of ominous drones and crackling static — or nothing more than the haunting wind whistling through the fields.

Arvo Part and Gyorgy Ligeti’s music is also used for part of the score, and adds considerable impact to the film, especially in the closing minutes. As a result, even seemingly tranquil scenes of the photographer riding down some rural path beneath a clear blue sky carry a vast undercurrent of dread. You almost expect some unnamed force to jump out from behind the trees and take him.

In one of the film’s most memorable scenes, the photographer just stands with his back to us, bicycle at his side, the dusty path to the village before him. Low, rolling hills stand off a short ways in the distance. The camera pans up over the man, but not enough so that we can see what’s lying ahead. However, we can hear what’s up ahead, a tangled mass of ominous sounds whose foreboding tone rumbles just beyond the horizon, as if foreshadowing some great dread, and on throughout the entire film.

Janisch matches the film’s sounds with some amazing visuals as well. Themes of spirals and mazes abound throughout the film, constantly creating a sense of inevitability. He renders the Hungarian countryside like a dream — one that isn’t quite a nightmare, but one that definitely has a certain off-ness to it. Plenty of bizarre sights do appear — an abandoned railway car full of decaying dolls with their eyes poked out, a severed sheep’s head here and there — which lend the film a certain David Lynch-esque quality, though with little of the “weirdness for weirdness’ sake.” And in the film’s final act, he employs some of the finest use of DV and slow motion I’ve ever seen, the former highlighting one of the film’s most significant moments, and the latter drawing out the girl’s murder into an agonizing experience of awareness (one made all the more affecting by Janisch’s restraint when it comes to the violence).

It’s this sense of atmosphere, this amazing tone that Janisch creates and sustains throughout the film’s two hours, that makes After the Day Before so enveloping even when the film’s plot borders on pretentious (barely any of the characters’ action or dialog seems believable), or even if you figure out the twist well in advance. And never mind the plot holes that are left behind in the film’s wake. It’s the long, slow reveal that makes After the Day Before what it is — a haunting and ominous treatise on memory, space, death, and sin.

Unfortunately, I was unable to stick around for the Q&A session following the film (I hadn’t realized the film’s runtime, and needed to book it to make the next film screening). I had a few questions of my own, and I would’ve loved hearing Janisch’s insights.