Mount Eerie’s A Crow Looked at Me Confronts the Horror of Death (Review)

We hate death, which is only right and proper. Death separates us from loved ones; it steals them from us, never to give them back. Death is preceded by fear and suffering, and more fear and suffering lie in its wake. Death respects no one; even the most noble, beloved, and innocent end up in the grave alongside the wicked and disgraced.

Even when death can be considered a release from suffering, the process of dying is terrible to behold. We watch helplessly as a loved one’s mind and/or body wastes away. We see them shamelessly stripped of those things that made them them, and the best we can do is make them comfortable while awaiting the inevitable.

I’ve lost friends and family to death, but I’d never seen the horror of death quite like when I walked into the room where my grandpa was dying. Over the course of six months, strokes and dementia had ruined his mind, and when I saw him that final time, he was in a coma that he never woke up from. I’ve never felt quite so helpless and sad, and when I sat down beside his bed, I broke down and wept.

So yes, death deserves our enmity. But in our right hatred of death, I fear we’ve become fearful of confronting death. Instead, we manage death’s awful reality with euphemisms. People don’t die; instead, they “pass away” and “go to a better place.” They become the “dearly departed” who are “at peace” and “in God’s hands.” In order to find some meaning in the meaninglessness of death, we even tell each other theologically dubious stories about how so and so died because “God needed an angel.”

To be fair, we often say such things out of kindness and a desire to spare those who are grieving additional distress. Or, if we’re the ones grieving, perhaps we say (and accept) them because we’re not ready to face the entirety of loss head on. For all their triteness, such phrases can give us space to process grief in our own time.

Even so, death is our last, great enemy. It is not simply another stage of life, as some might believe. It is a perversion of God’s good creation, and one that will assuredly be destroyed (1 Corinthians 15:26, Revelation 20:14). We should hate it and be troubled and disturbed by it. At the same time, we should not be afraid to name it for what it is and what it does.

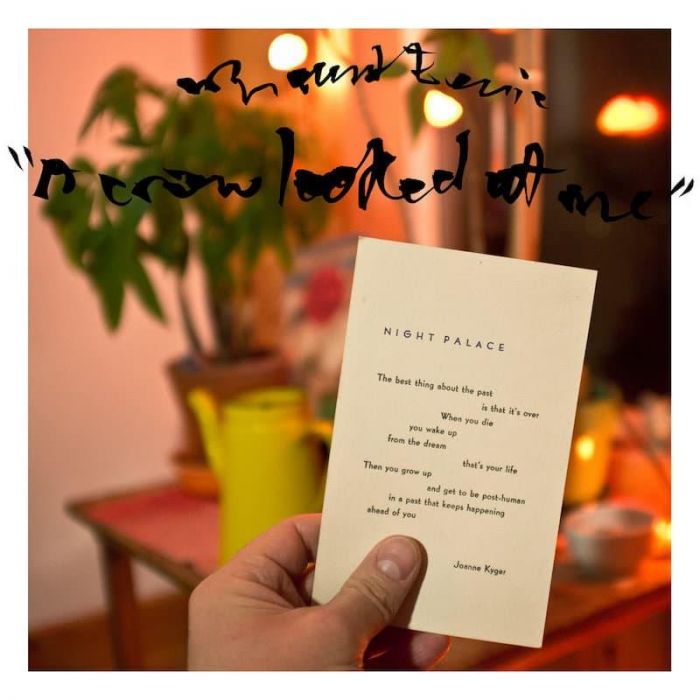

Recent years have brought several albums that are honest confrontations of death, including Sufjan Stevens’ Carrie and Lowell and Nick Cave’s The Skeleton Tree. This year brings another: Mount Eerie’s A Crow Looked at Me. Mount Eerie’s Phil Elverum has always sung about the fragility of human existence. But on A Crow Looked at Me, he explores that fragility like never before.

Four months after the birth of their first child, Phil and his wife, Geneviève, received devastating news: Geneviève had inoperable stage four pancreatic cancer. She died the following year, leaving behind a young daughter and a husband reeling with grief.

Recorded in the months following Geneviève’s death in the same room where she died, and with many of her instruments, A Crow Looked at Me is not an easy album to listen to — and not just because of the sad story of its genesis. It is, however, frequently beautiful and heart-wrenching, and suffused with deeply human pain and longing as Elverum struggles to exist in a world that no longer contains his wife.

The album begins with three simple words: “Death is real,” a phrase that pops up throughout the album. From the outset, Elverum leaves no room for euphemisms, but instead, faces the reality of death and its effects (“When I walk into the room where you were / And look into the emptiness instead / All fails / My knees fail / My brain fails / Words fail”). He weeps after receiving a backpack in the mail that Geneviève had ordered for their daughter even as she was, as Elverum puts it, “being swallowed into a silence that is bottomless and real.”

And so it goes for 11 songs. On paper, Elverum’s lyrics are frequently jumbled and random, little sketches of memories of Geneviève, many of them scribbled at her bedside as he kept watch during her final days. One might accuse Elverum of cramming too many words into his songs, stream of consciousness-like. But that awkwardness only makes A Crow Looked at Me more direct, piercing, and human. After all, grief isn’t rational or given to nice, neat organization.

During “My Chasm,” Elverum considers the gulf now separating himself from everyone else. He bluntly asks, “Do the people around me want to keep hearing about my dead wife? / Or does the room go silent when I mention you?” and ruefully observes that he now has “the power to transform a grocery store aisle into a canyon of pity and confusion and mutual aching to leave.”

“When I Take out the Garbage at Night” contains one of the album’s most poignant images, as Elverum uses mundane chores to momentarily escape the house where Geneviève died (“When I take out the garbage at night / I’m not with you then exactly / I’m with the universe / And with the lightning and thunder coming in over the mountains”). But grief, like life, continues, so the song ends on a resigned note; he still has to “go back in and live on.”

Previous Mount Eerie albums, such as 2009’s Wind’s Poem, are full of striking, if disquieting, ruminations on man’s insignificance in the face of nature’s implacable forces. A Crow Looked at Me finds Elverum tempering that a bit. (On “Emptiness, Pt. 2,” he even digs at his earlier artistry, singing, “Conceptual emptiness was cool to talk about / Back before I knew my way around these hospitals.”)

Elverum does occasionally find comfort in nature’s vastness. “Ravens” is arguably the album’s centerpiece, a sprawling piece of hushed acoustic guitar, ominous piano notes, and stark reminders of Geneviève’s absence (“Now I can only see you on the fridge in lifeless pictures”). But as Elverum releases his wife’s ashes on the beach in the song’s denouement, he observes a landscape full of “nurse logs with layers of moss and life… The ground absorbs and remakes whatever falls. / Nothing dies here.” Life goes on, he seems to realize with relief.

But elsewhere on A Crow Looked at Me, nature’s grand rhythms fail to comfort Elverum. Against a backdrop of summer forest fires, Elverum sings, “The devastation is not natural or good / You do belong here / I reject nature / I disagree” (“Forest Fire”). Later, he even feels mocked by those rhythms: “The grind of time I’m not keeping up with / The leaf on the ground pokes at my slumbering.”

The most affecting moments in Mount Eerie’s discography are when Elverum peers past the darkness and human frailty and, instead, glimpses something more sublime, mysterious, and even eternal. In the notes for A Crow Looked at Me, he writes:

These cold mechanics of sickness and loss are real and inescapable, and can bring an alienating, detached sharpness. But it is not the thing I want to remember. A crow did look at me. There is an echo of Geneviève that still rings, a reminder of the love and infinity beneath all of this obliteration. That’s why.

And so, the album’s final moments describe a haunting experience he has while hiking with his daughter:

In my backpack you were sleeping with her hat pulled low

All the usual birds were gone or freezing

It was all silent except the sound of one crow

Following us as we wove through the cedar grove

I walked and you bobbed and dozed…

We were watched and followed and I thought of Geneviève“Crow” you said. “Crow.”

And I asked, “Are you dreaming about a crow?”

And there she was.

The album abruptly ends after those final words, leaving the listener in a state of ambiguity. Something seems to happen in those lyrics. A moment of closure and resolution, perhaps? A small ledge of stability and hope in the midst of grief? In any case, the preceding lyrics and music make it clear there’s still much grieving to do.

At one point on A Crow Looked at Me, Elverum sings what could easily be a warning for us listeners: “We are all always so close to not existing at all.” This is not something we moderns like to hear, though, for its implication is clear: we possess far less control over our lives (and deaths) than we’d like to think. We want to believe that we’ll live long, fruitful, prosperous lives full of comfort. That’s our hope, anyway.

In and of itself, that’s not a bad thing — but it can be misleading. Go too far down this path, and death becomes a mere afterthought. I suspect this is doubly true for Christians, as we find comfort in Christ’s victory over sin and death. In our disregard of mortality, we can treat Christ’s suffering and death too carelessly (if we consider them at all). But Christ’s victory doesn’t make much sense — it’s not much of a victory — unless we see death as Elverum does, as a cold reality that otherwise leaves us shaken and torn.

A Crow Looked at Me is nothing if not a constant reminder that death is a horror not to be dismissed or treated lightly. In that regard, it’s a deeply courageous album, one created literally within the presence of death. As such, it’s unafraid to confront death head-on and reveal it for the terrible thing that it is.

But while it’s a deeply sad album, and the lyrics sometimes contain snatches of dry, black humor, A Crow Looked at Me is not morbid. Even as he mourns his wife, Elverum’s love for Geneviève shines through in every single second. (He writes, “I make these songs and put them out into the world just to multiply my voice saying that I love her.”)

It’s a privilege to listen to an album like this, to be welcomed so openly into someone else’s grief, difficult and awkward as it is. And as Elverum pours out his heart and longs deeply after his absent wife, struggles with raising their daughter on his own, and readjusts to a new, sorrowful normal, we are given a clear and intimate portrait of the effects of the Fall.

As we see those effects in their awful entirety — as I did with my dying grandpa — there is fear, confusion, anger, and grief to be sure. But more than that, such a sight is also a harrowing reminder that we are powerless to save ourselves from death’s cold emptiness. We need something — or Someone — else. Death is most certainly, and terrifyingly, real. But is it not the end. It does not have the final word.

This entry was originally published on Christ and Pop Culture on .