When C.S. Lewis met G.K. Chesterton

More good stuff from Jake Meador’s class on the Christian imagination. First, regarding the pre-conversion C.S. Lewis:

For the pre-conversion Lewis, the entire cosmos was empty, devoid of intent and hostile to life. Humanity was the most civilized product of that aimlessness and so humanity ought to preserve itself. But the universe is a hostile place, so there’s always going to be a defensive, us-against them, zero sum basis for Lewis’ attitude toward the world, pre conversion. In some ways, his view of the world takes us back to Homer: The world is essentially chaotic, there is no right or wrong, no fixed trajectory, no narrative.

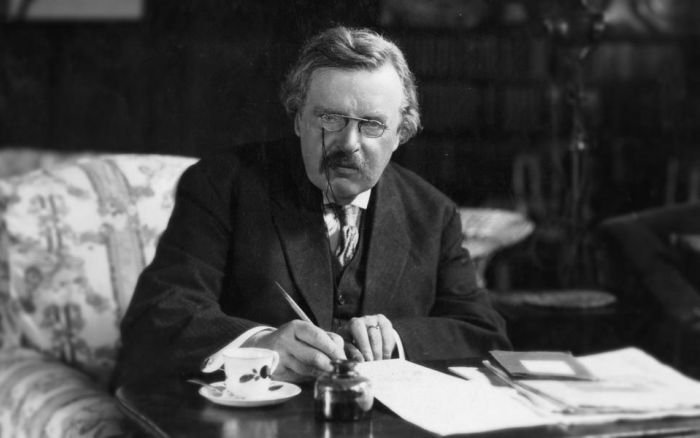

Lewis was also a firm believer in the ability of humanity to continue improving itself by extending its rule over nature through the use of technology, science and reason. Essentially, man exists in a state of perpetual war against the chaotic nature of the cosmos. This materialistic pessimism was not uncommon during Lewis’ day. It was a popular line of thought in the late 19th and early 20th century: You’ll find echoes of it in Nietzsche, George Bernard Shaw, and H.G. Wells (all men that Chesterton debated quite vigorously in print, in live debates, or both). Not only was this line of thought common enough, but Lewis’ personal life made it almost inevitable that he would at least be attracted to it.

He then goes on to discuss Chesterton and his prose, which was instrumental in C.S. Lewis turning to the Christian faith. He quotes from Philip Yancey’s excellent Chesterton intro in Soul Survivor:

Chesterton viewed this world as a sort of cosmic shipwreck. A person in search of meaning resembles a sailor who awakens from a deep sleep and discovers treasure strewn about, relics from a civilization he can barely remember. One by one he picks up the relics — gold coins, a compass, fine clothing — and tries to discern their meaning. Fallen humanity is in such a state. Good things on earth — the natural world, beauty, love, joy — still bear traces of their original purpose, but amnesia mars the image of God in us.

For Chesterton, and also for me, the riddles of God proved more satisfying than the answers proposed without God. I too came to believe in the good things of this world — first revealed to me in music, romantic love, and nature — as relics of a wreck, and as bright clues into the nature of a reality shrouded in darkness. God had answered Job’s questions with more questions, as if to say the truths of existence lie far beyond the range of our comprehension. We are left with remnants of God’s original design and the freedom, always the freedom, to cast our lots with such a God, or against him.

In addition to the problem of pain, G.K. Chesterton seemed equally fascinated by its opposite, the problem of pleasure. He found materialism too thin to account for the sense of wonder and delight that gives an almost magical dimension to such basic human acts as sex, childbirth, play, and artistic creation.