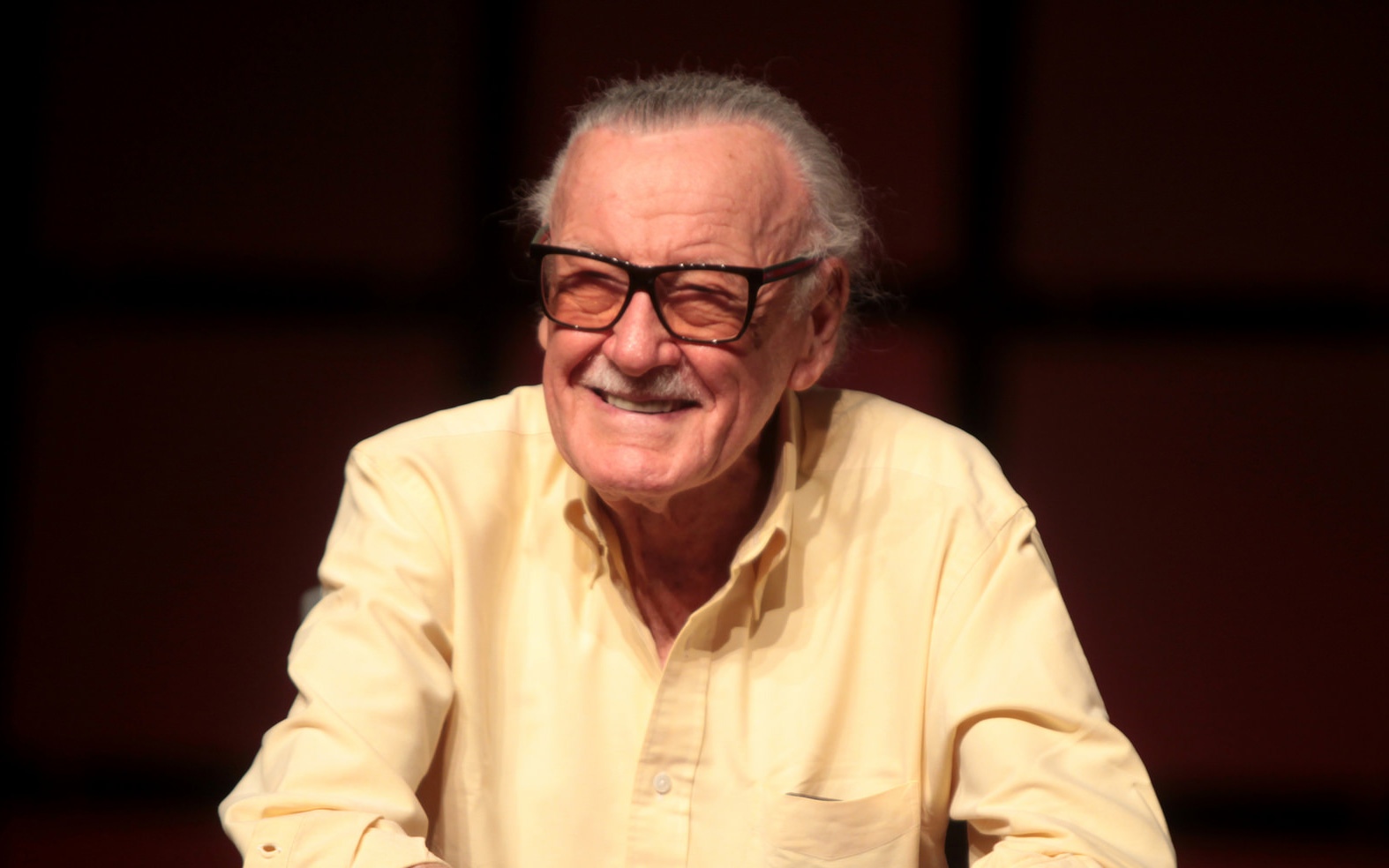

The Comic World as We Know It, Thanks to Stan Lee (1922-2018)

When I learned about Stan Lee’s death and began reading about his life and legacy, I was a little taken aback by how emotional I was becoming. But on second thought, I really shouldn’t have been surprised. Lee’s creations at Marvel Comics brought so much joy, entertainment, and even awe into my life, and the lives of countless others. Furthermore, his messages of humanism and tolerance, and his stories of flawed, relatable heroes, never failed to inspire, delight, and entertain.

While characters like Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four, Hulk, and the X-Men are understandably the first ones that come to mind when talking about Lee, for me, his most indelible creation was the Silver Surfer. The Surfer was one of Lee’s favorite characters, and he used him for some of his most thoughtful stories as the noble alien observed humanity in all of its glory and squalor.

Lee’s focus on his heroes’ humanity was what set his stories apart. His heroes weren’t demigods. Rather, they were flawed, broken, and behind their masks, ordinary folks who faced the same problems that people might face in real life: youthful awkwardness (Peter Parker), interpersonal issues (the Fantastic Four), struggles for acceptance and belonging (the X-Men). What made Lee’s heroes super wasn’t their powers, but rather, their willingness to do the right thing, no matter the cost.

Lee’s life was not without controversy. Professionally, he was criticized for how he treated his collaborators, including Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, and taking more than his fair share of credit. His post-Marvel endeavors, like POW! Entertainment, made some questionable deals and creations (e.g., Stripperella). Personally, he was plagued by family feuds, allegations of sexual assault, trusted associates bilking him for millions, and even having his blood reportedly stolen to create fake autographs.

But in spite of any and all controversies, it’s nigh-impossible to overstate Stan Lee’s influence and impact on pop culture. For better or worse, the world of comics will probably forever be in his shadow. But perhaps his greatest legacy will be that he never treated comics and superheroes as mere disposable entertainment. Rather, he recognized their power and importance in people’s lives. As he put it:

I used to be embarrassed because I was just a comic book writer while other people were building bridges or going on to medical careers. And then I began to realize: entertainment is one of the most important things in people’s lives. Without it, they might go off the deep end. I feel that if you’re able to entertain, you’re doing a good thing.

As would be expected, a host of tributes to Stan the Man have come pouring in. I particularly enjoyed this remembrance by Jim McLauchlin, who regularly had lunch with Lee for two decades:

After 95 years, Stan remained remarkably consistent. Walking down the street, he’d move faster than you, even in his tenth decade. He’d happily wave at people who recognized him. He’d sprint a couple steps ahead to open a door for a lady. And over the years, I saw him happily autograph dozens of slightly soggy Cheesecake Factory napkins.

The voice you heard in movies and cartoons was the voice he had every day. It commanded, if it didn’t boom, and always had a friendly quality. Witticisms and puns would flow, along with Shakespeare quotes — Stan loved the classics. And the tone and timbre was always enthusiastic.

“I get excited easily,” he’d say. “I live a nice life, and I’m usually very happy. Why not share a little of that?”

Author Michael Chabon wrote about the warm humanism that Lee brought to his comics:

[Stan Lee]’s creative and artistic contribution to the Marvel pantheon has been debated endlessly, but one has only to look at [Jack Kirby]’s solo work to see what Stan brought to the partnership: an unshakable humanism, a faith in our human capacity for altruism and self-sacrifice and in the eventual triumph of the rational over the irrational, of love over hate, that was a perfect counterbalance to Kirby’s dark, hard-earned quasi-nihilism. In the heyday of their partnership, it was Stan’s vision that predominated and that continues to shape my way of seeing the world, and of telling stories about that world, to this day.

David Sims discussed Lee’s approach to making comics (aka, “The Marvel Method”):

Lee relied on a writing approach he dubbed “the Marvel method,” where he would create a short story synopsis, the artists would draw the story themselves and create the plot-by-plot details, and then Lee would fill in the dialogue (he was fond of hyperbolic narration, goofy one-liners, and topical references).

That method led to many disputes over the years with Lee’s top collaborators. Certainly visionaries like Kirby and Ditko deserved just as much credit for the characters they created, though Lee was often reticent to grant it. The extent of Lee’s contributions to any particular Marvel Comics issue can be argued over endlessly, but the writer played a huge role in making comic-book storytelling what it is today. He emphasized character as much as action; was fond of serialized, soapy twists; and tried to keep his heroes relevant to the age they lived in, rooting stories in the countercultural movements of the day.

Meanwhile, Brian Michael Bendis reflected on Lee’s influence in his own life — and did so in the most appropriate way, a web comic drawn by Bill Walko. And Jason Johnson has written a beautiful piece about Lee’s activism against bigotry and racism, and how it impacted him as a child:

It is hard to overstate how important Lee is to black kids growing up in the 1980s and ’90s back when comic books were considered a “white” thing. I have literally teared up a few times while writing and thinking about how much joy he brought to youngsters like me, and how much his passion and excitement for comic books helped validate this hobby and the culture that goes with the genre. More than any other golden age comic creator Lee’s characters put blackness and the black experience at the forefront.

When Lee created the X-Men in 1963, the battle between Magneto and Professor X was meant to be a rough allegory for the integrationist vs. nationalist philosophies of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. Yes, the idea of black oppression and philosophy being played out by mostly protestant white guys like Cyclops and Ice-Man is problematic in hindsight (Magneto is Jewish), but it was a radical idea at the time. It also laid the groundwork for a comic that always spoke to racial injustice, even to kids like me who loved comics but seldom saw themselves in the stories and shows of the genre.

Needless to say, watching Avengers 4, and presumably the final Stan Lee cameo, will be a very bittersweet experience. Rest in peace, Stan Lee, and of course, excelsior!

This entry was originally published on Christ and Pop Culture on .