Staring Into the Sleepy Eyes of Death, An Unsung Samurai Cinema Classic

Broadly speaking, many samurai movies (aka chanbara or jidaigeki movies) can fall into one of two camps. The first is the “arthouse” camp, which includes Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, Masaki Kobayashi’s Harakiri, and more recently, Yôji Yamada’s Twilight Samurai. “Arthouse” samurai films feature elegant and epic filmmaking, stunning action set pieces, and deeply humanistic, elegiac storylines that explore lofty, “serious” topics: bushidō (the samurai code of honor), family and clan loyalty, and the clash between revered tradition and social and cultural change.

The second is the “exploitation” camp. These films feature grittier, more explicit and sensational storylines and are more graphic concerning sex and violence. Two of the most famous examples of “exploitation” samurai cinema are the Lone Wolf and Cub and Lady Snowblood films. The former follows a disgraced executioner and his infant son as they seek revenge on a rival clan for destroying their family. In the latter, a young woman becomes an assassin in order to kill those who raped and killed her family. In both series, the protagonists leave behind a bloody trail, the result of bizarre, over-the-top fights and action sequences.

The lines between the two camps are, of course, blurred. Kurosawa’s films certainly contained plenty of bloody violence (e.g., Sanjuro’s climactic duel) while the Lone Wolf and Cub films have been praised for their highly stylized aesthetic. But one of the best examples of this blurring between “arthouse” and “exploitation” fare are the Sleepy Eyes of Death films that were released between 1963 and 1969 by the Daiei Film studio.

Arguably the most popular adaptation of Renzaburō Shibata’s novels and short stories, the long-running Sleepy Eyes of Death series follows a cynical rōnin (i.e., masterless samurai) named Nemuri Kyoshiro who always seems to find trouble no matter where he goes in Tokugawa-era Japan. In just seven years, Daiei produced twelve Sleepy Eyes of Death films starring celebrated actor Ichikawa Raizō as the samurai antihero.

- The Chinese Jade (1963)

- Sword of Adventure (1964)

- Full Circle Killing (1964)

- Sword of Seduction (1964)

- Sword of Fire (1965)

- Sword of Satan (1965)

- The Mask of the Princess (1966)

- Sword of Villainy (1966)

- A Trail of Traps (1967)

- Hell Is a Woman (1968)

- In the Spider’s Lair (1968)

- Castle Menagerie (1969)

(Daiei Film produced two more Sleepy Eyes of Death films after Raizō’s untimely death in 1969, with Matsukata Hiroki taking over the lead role. I’m choosing, however, to focus only on the Raizō films.)

The main hook of the Sleepy Eyes of Death series, which initially sets it firmly in the “exploitation” camp, is Kyoshiro’s shameful origin. His mother was a Japanese noblewoman who was kidnapped and subsequently raped during a black mass by his father, a Christian missionary who apostatized and became a devil worshiper. (This explains the series’ other title: Son of the Black Mass.)

This “halfbreed” heritage, as evidenced by his pale complexion and reddish hair, makes Kyoshiro a permanent outsider. Not surprisingly, he possesses a deep hatred for Christianity and Japanese society alike. He considers both of them weak, corrupt, and full of hypocrisy — a view that inevitably lands him in trouble during his travels.

Fortunately for Kyoshiro, he’s more than capable of defending himself thanks to his mastery of the “Full Moon Cut” swordfighting style. At the climax of every duel, Kyoshiro stands tall and begins tracing a circle in the air with his katana. His opponent, unable to resist attacking, rushes forward and is struck down before the circle’s completion. In later films, this attack takes on a psychedelic look, with strobe effects giving the “Full Moon Cut” an otherworldly quality as it lures Kyoshiro’s opponents to their inevitable death.

Kyoshiro’s shameful heritage and fearsome reputation don’t scare off everyone, though. Nearly every Sleepy Eyes of Death film contains at least one woman who can’t resist the rakish rōnin’s charms. Instead, they pout over his womanizing, try to get him to change his bloody ways, and/or scheme to bed him. Indeed, one of the series’ primary antagonists is Princess Kiku, a disfigured and disgraced daughter of the Shōgun who becomes obsessed with both bedding and killing Kyoshiro after he repeatedly thwarts her depraved schemes.

In any case, Kyoshiro usually rebuffs the women’s advances or takes advantage of their obsession to have his way with them (usually while mocking their feminine wiles and uncovering whatever scheme they’ve been plotting). And if nothing else works, there’s always his katana. Kyoshiro, as it turns out, is as skilled at disrobing women with his blade as he is killing other samurai.

As the series progressed, Daiei upped the exploitative quotient, and most notably in the last few films: In the Spider’s Lair features a set of (possibly incestuous) twins, one of whom flaunts her body in front of Kyoshiro to his jaded amusement while Castle Menagerie has a nightmarish, dream-like sequence quite unlike anything else in the series.

Still, they’re far less explicit than you might think based on the above descriptions. As Richard Meyers writes in Great Martial Arts Movies:

Would you believe that these movies were done with high style and surprising taste? It’s true. Although beyond the comprehension of many Western eyes, the [Sleepy Eyes of Death] movies were done with demure sophistication. There was no complete nudity… and very little blood onscreen.

Those expecting the Sleepy Eyes of Death films to be similar to the infamous Hanzo the Razor series or the softcore “pink” films that had become increasingly popular in ’60s-era Japan will almost certainly be disappointed. Then again, looking to these films for gratuitous content overlooks their most interesting angle: despite his cynical and boorish ways, Kyoshiro often comes across as something akin to a wounded idealist.

It’s a seemingly small detail, but it gives the Sleepy Eyes of Death films a surprising depth that moves them closer to the “arthouse” end of the spectrum.

The series’ first film, The Chinese Jade, lands Kyoshiro in a conspiracy involving a valuable statue. By the film’s end, he’s seen firsthand how the depravity of greedy, selfish men destroys innocent lives. After the villains have all been dispatched, he disdainfully throws the prized statue into the ocean. As the elements batter his body, Kyoshiro wonders aloud, “Is there still beauty anywhere in this world?,” anguish etched on his face.

It’s a question that haunts the rest of the series.

Lurking beneath Kyoshiro’s misanthropy and misogyny is a tension — a desire to find, and even latch onto, something honorable in life. Which explains why he frequently expresses contempt for Japanese nobility and defends those they oppress, and occasionally, even expresses regret for his lifestyle.

- In Sword of Seduction, Kyoshiro allies himself with persecuted Christians despite his hatred for their religion.

- Sword of Fire ends with Kyoshiro allowing his reputation as a swordsman to be sullied in order to prevent a naïve young girl from discovering her own shameful parentage.

- Finally, Sword of Satan might have the series’ most salacious title, but it features Kyoshiro at his noblest and most pensive. After his contempt and dismissiveness leads to a woman’s death, he seeks to atone for his “bad karma” by protecting her young son from a clan’s evil machinations.

Unfortunately, Kyoshiro’s desire is almost always thwarted by corrupt nobles and government officials, commoners with their petty squabbles, and hypocritical religious leaders.

A shocking example of this occurs in Sword of Seduction. After getting involved in the plight of some persecuted Christians, Kyoshiro witnesses an imprisoned Christian missionary succumb to temptation and sleep with a woman as part of a scheme to make him apostatize. Kyoshiro beheads the disgraced Christian in anger for failing to remain faithful to his vows — vows that, ironically, Kyoshiro actively scorns. (As for the woman, she offered herself to the missionary to save her brother, who’s still crucified for practicing Christianity. Needless to say, her persecutors eventually get their comeuppance from Kyoshiro’s blade.)

Sword of Satan — arguably the series’ best film thanks to the complexity we see in Kyoshiro’s character — features an even bleaker example. While exposing a clan’s vile activities, Kyoshiro interrupts a black mass that’s being used as a cover for performing abortions. Kyoshiro condemns the false priest before killing him:

Fallen Christian! With one hand, you were performing abortions and with the other, you presided over satanic torture and murder! You’re but a damned dog on the loose. A dog that spits on your God’s mercy!

He then proceeds to slaughter all of the evil samurai who were complicit in the priest’s “satanic torture and murder.” (And there were a lot of them.)

Suffice to say, most Sleepy Eyes of Death films end with Kyoshiro wandering off into the countryside while leaving more than just a few corpses in his violent wake — his cynical worldview affirmed once again.

At the risk of damning the series with faint praise, another aspect that lands the Sleepy Eyes of Death series squarely between the “arthouse” and “exploitation” ends of the spectrum is the workman-like quality with which they were made. Though well done, no one would ever confuse them for, say, a Kurosawa film; don’t come to these movies expecting any sort of bravura or auteur-like filmmaking.

Also, given that they were directed by a revolving door of jidaigeki directors like Kenji Misumi (who would later create the Lone Wolf and Cub series) and Kimiyoshi Yasuda (who directed several Zatoichi films), there’s no real consistent cinematic aesthetic throughout the series’ films. This explains why there are tonal shifts throughout the series, for better or worse, and why the films feel self-contained and wholly disconnected from the ones that come before and after.

This episodic nature, combined with Daiei’s obvious decision to spend as little money as possible on these movies while releasing as many of them as possible, results in the films looking a bit cheap from time to time, like glorified television period dramas.

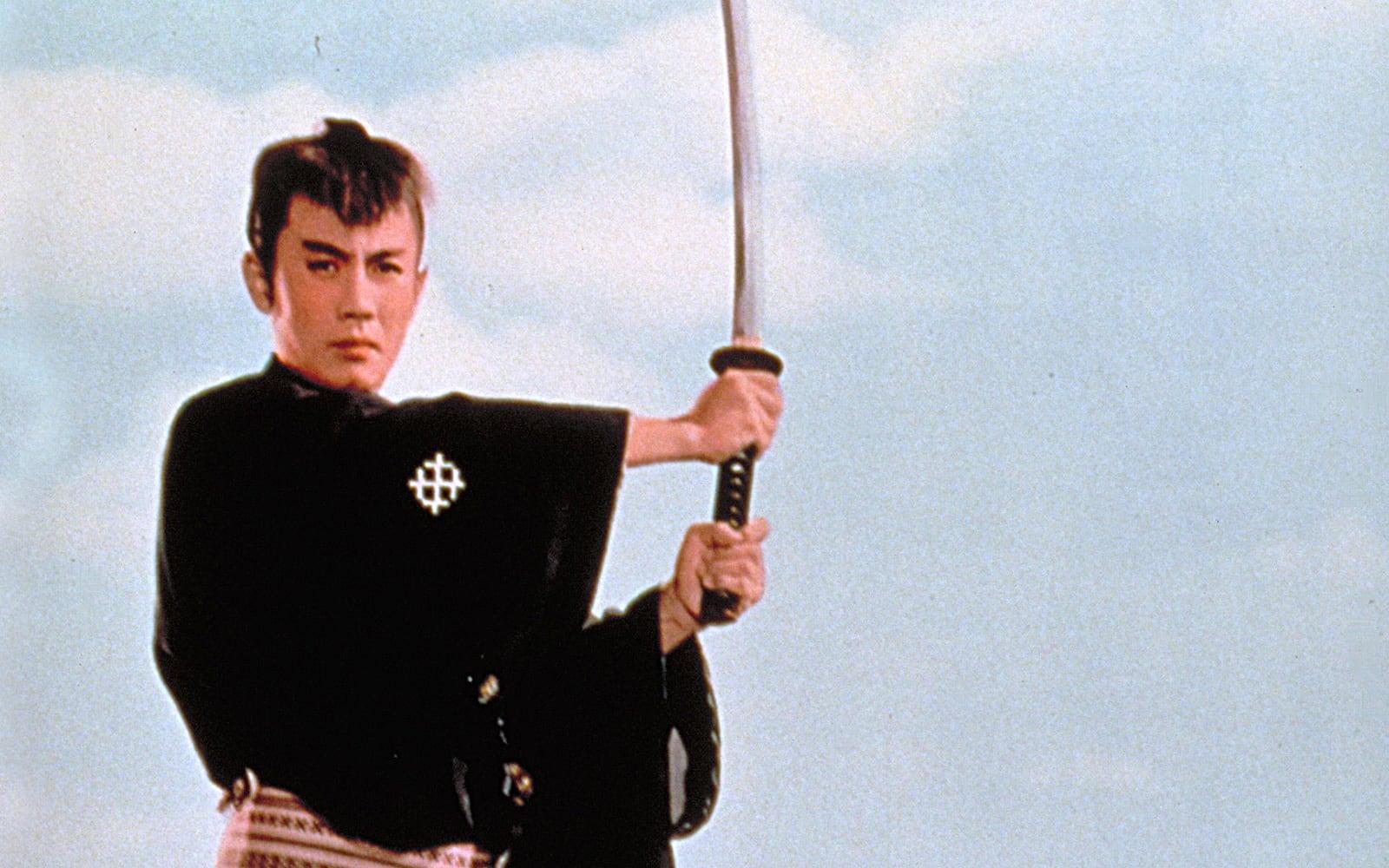

The films’ main draw really is Ichikawa Raizō’s performance as the cynical rōnin. Sometimes compared to James Dean because of his handsome looks, Raizō — born Akio Kamezaki in 1931 — got his acting start in kabuki as a teenager. Frustrated by his kabuki career, he went to work for Daiei Film at the age of 23 in their jidaigeki films. In all, Raizō starred in over 150 films over a 15-year career — a career that was tragically cut short by cancer at the age of 37. But without a doubt, the Sleepy Eyes of Death films are his most famous and celebrated performances.

Though often bearing a haughty or disdainful expression, especially when confronted with yet another example of government corruption or religious hypocrisy, Raizō could reveal the more complex emotions swirling within Kyoshiro with the subtlest change in expression or hint of body language. It would be easy for Kyoshiro’s cynicism to become a schtick by the third or fourth film, but to Raizō’s credit, he kept it interesting. The same holds for the “Full Moon Cut,” which happens several times in each film — but every time Kyoshiro begins tracing that deadly pattern in the air, it’s spellbinding.

I learned of the Sleepy Eyes of Death series years ago, long before streaming services were even a glimmer in some tech entrepreneur’s eye. The only option was to purchase them via mail order from AnimEigo, a distributor of Japanese film and anime famous for their in-depth translations and liner notes. Nowadays, though, watching the Sleepy Eyes of Death films is as easy as a Google search.

However, I was pleased to find the AnimEigo versions streaming on Hoopla (which, by the way, is free with a library card). The AnimeEigo versions are excellently subtitled, even translating onscreen text and providing the odd historical note to provide context for certain scenes. More such info can be found in AnimEigo’s liner notes. (On a sidenote, Hoopla streams several other AnimEigo titles, including the first four films in the Shinobi no Mono series, which also star Ichikawa Raizō as celebrated outlaw/ninja Goemon Ishikawa, and the Bubblegum Crash and A.D. Police anime series.)

While I wouldn’t consider these films totally accurate representations of Tokugawa-era Japan, their historical elements — the Shōgun’s supremacy and the dominance of the samurai, the rigid stratification and deep unrest of Japanese society at the time, the brutal persecution of Christianity — do help ground them amidst Kyoshiro’s outlandish and violent adventures. And AnimeEigo’s notes help to make that context more apparent. As such, I highly recommend watching these versions rather than some random YouTube upload.

They’re an interesting slice (npi) of samurai cinema that is often overshadowed by more famous examples on either end of the arthouse/exploitation spectrum. But thanks to an intriguing premise and a riveting lead actor, they’re definitely worth a look for any chanbara devotee.

Images courtesy of AnimEigo.