Star Trek: The Motion Picture: Ambitious, Awe-Inspiring… and Boring

I recently got an urge to rewatch all of the Star Trek movies, most of which I probably haven’t seen in over a decade. We started, of course, with Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), in which James T. Kirk and the Enterprise must intercept a vast, immeasurably powerful alien entity named V’Ger that’s heading towards Earth, determine how to communicate with it, and if necessary, somehow stop it from destroying the planet.

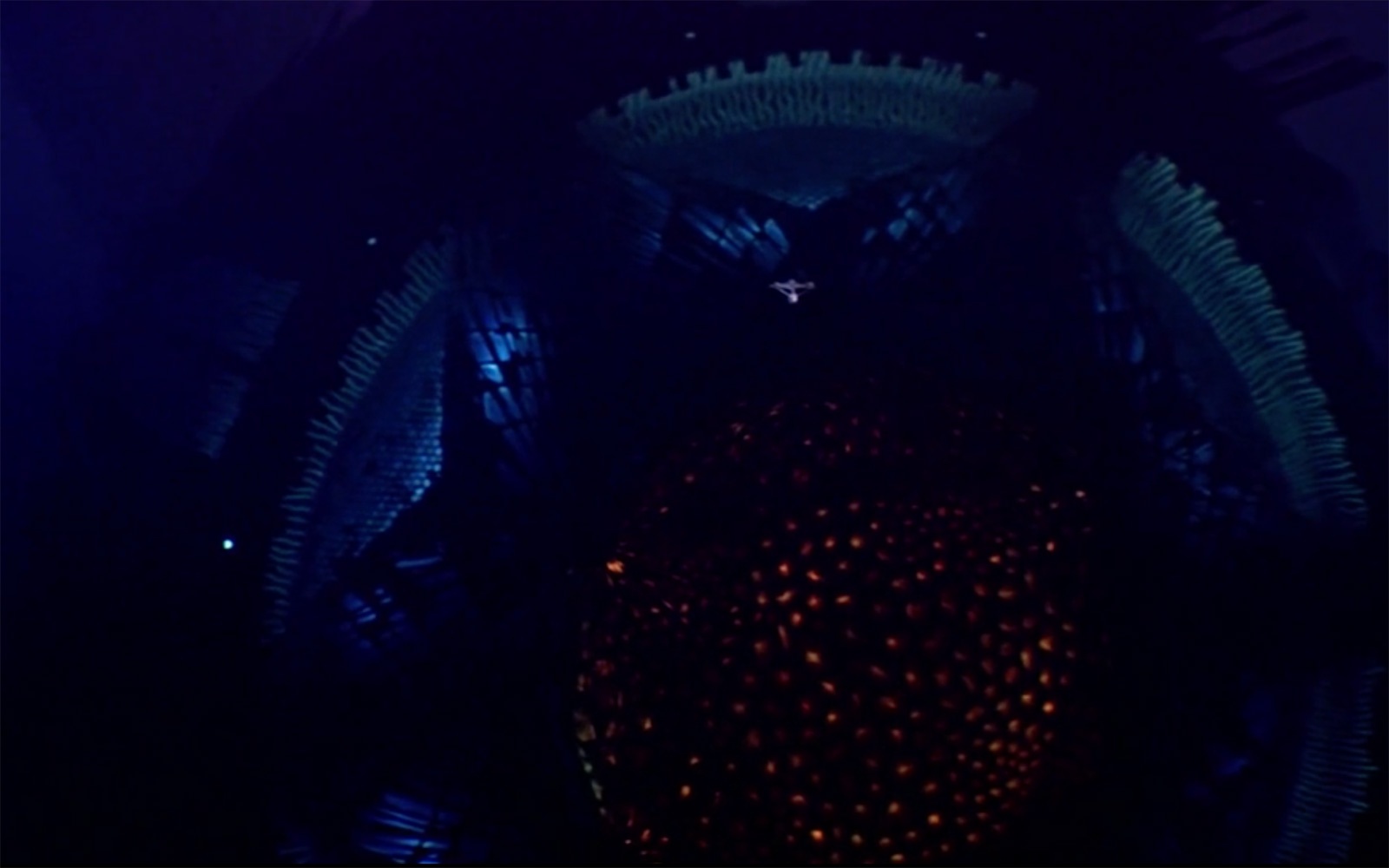

Watching it with my kids, I was struck by a couple of realizations. First, The Motion Picture might be the most ambitious of the Star Trek films, specifically in how it tries to convey V’Ger’s mind-boggling scale and utter alienness. Though it’s been said that The Motion Picture was an attempt to cash in on the burgeoning Star Wars craze, which began two years earlier, I’ve always considered The Motion Picture to be an attempt at 2001: A Space Odyssey’s sense of scale and cosmic awe.

For all its flaws (more on those in a bit), there are moments in The Motion Picture — as the Enterprise ventures deeper into V’Ger and encounters alien technology so massive and advanced it beggars belief — that are awe-inspiring and unlike anything else in the franchise. (This is almost certainly due to special effects maestro Douglas Trumbull, who had also worked on 2001. He began working on The Motion Picture after completing Close Encounters of the Third Kind, yet another film full of awe-inspiring visuals.)

At the same time, The Motion Picture might very well be the most boring Star Trek movie; it certainly doesn’t have the same joie de vivre that one experiences in The Wrath of Khan or The Voyage Home. *

The film’s pacing positively crawls at times, even beloved and familiar characters feel stiff and wooden (with the exception of the perpetually irascible Dr. McCoy), and I’m pretty sure that at least a third of it consists of nothing more than people’s reaction shots as they try to look overwhelmed by V’Ger’s majesty. Kudos to director Robert Wise — who also directed The Day the Earth Stood Still, West Side Story, and The Sound of Music — for adhering to the maxim of “show, don’t tell,” but once you’ve seen one reaction shot in The Motion Picture, you’ve basically seen them all.

When we watched The Motion Picture, I didn’t put two and two together and realize that this year marks the film’s 40th anniversary (meaning that a theatrical re-release is on the way). But James Whitbrook has posted a lengthy review of the film in light of its anniversary, and specifically, the “beautifully dull paradox” that it represents.

[I]t’s so much easier to remember those things than what The Motion Picture is actually about: a slow-moving deadly cloud dragging its way towards Earth. The entity at the heart of said space cloud, V’Ger, turns out to be one of Earth’s original Voyager probes, damaged on its deep space mission and fixed up by mysterious cosmic entities, given unfathomable sentience and power but not the power of loooooove. The film also features a weirdly curmudgeonly Captain (now Admiral/desk jockey) Kirk, with little of the charm he’s beloved for, bullying his way back into command of the Enterprise to meet the threat. Seemingly endless chit-chat and a cursory sacrifice of both of the film’s intriguing new characters, Ilia and Decker, to teach V’Ger about the human connection later and our bridge crew is back and ready to boldly go where no one has gone before all over again.

[…]

Despite these fatal flaws, and beneath its languid pacing, The Motion Picture also speaks to the heart of what Star Trek is about; it shows us the grand, haunting, wild and sheer weirdness of space exploration, of encountering the unknown. Perhaps not quite the boldly going of that iconic opening bit from Kirk that accompanied every episode of Star Trek, perhaps not quite even the where no one has gone before, given that this movie is essentially a remake of the season two episode “The Changeling” stretched to a breaking point. But it still invites us to indulgently revel in the beautiful spectacle of the final frontier, to evoke those feelings of Capital-R-Romantic, exploratory wanderlust. It hopes that we, like its heroes, will spend so many of its lavish special effects sequences — some more enduring than others, these days — simply staring in awe as Jerry Goldsmith’s equally awe-inspiring soundtrack blares into your ears.

I certainly agree with Whitbrook’s point in that last paragraph. So many Star Trek movies decidedly lack the franchise’s definitive themes, specifically of exploring strange new worlds and seeking out new life and new civilizations. Many Star Trek movies are more akin to thrillers, capers, and action movies set in space, and while there’s nothing wrong with that, it does leave one wanting for a bit of actual exploration — which The Motion Picture, for all its faults, has in spades.

One more thing: though Whitbrook’s right about Jerry Goldsmith’s score, The Motion Picture also works quite nicely with the music of Daft Punk, specifically their soundtrack for Tron: Legacy.

* — I should note that we watched the theatrical version of The Motion Picture. I’m curious what my reactions would’ve been had we watched the “director’s cut” that was released in 2001. Featuring numerous re-edits, updated and improved special effects, and a remixed soundtrack, it’s widely considered to be superior to the theatrical version. Alas, it’s not available on Hulu.