Some Thoughts on Ridley Scott’s Changes in the “Final Cut” Of Blade Runner

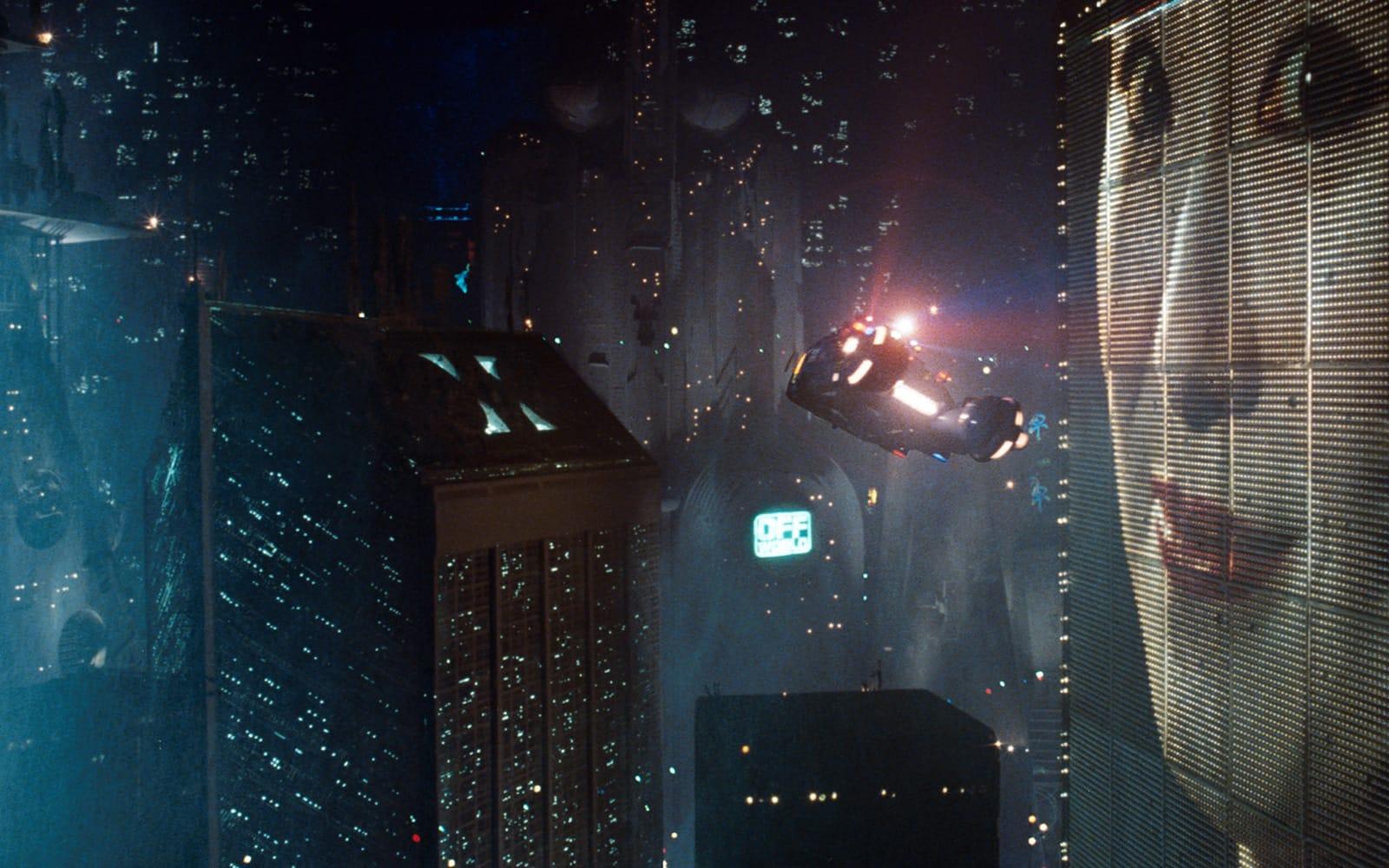

One of my favorite films, Blade Runner, is a film that I constantly go back to and always find something new and fascinating to watch, and whose beauty I never get tired of seeing. That being said, I finally got around to watching the “Final Cut” this weekend, which was released last year as part of the recently released “Ultimate Collector’s Edition” DVD set.

The “Final Cut” is director Ridley Scott’s approved version, and the only version over which he had complete artistic control. Previous versions, including the theatrical release and the so-called “Director’s Cut,” contained a fair amount of studio meddling. (Wikipedia has more info on the various versions.)

While Blade Runner has always been a beautiful film to watch, the “Final Cut” is even moreso. No doubt the digital remastering and retouching helped quite a bit, giving the film an extra layer of polish that was missing in the past. But there are two differences with the “Final Cut” that I personally found significant. They certainly don’t lessen my enjoyment or appreciation of the film, but they do change the way I interpret and contemplate the film’s themes and ideas.

I’m about to venture into spoiler territory, so if you haven’t seen the film, you might want to stop reading now.

I want more life…

The first difference occurs when Roy Batty, the leader of the renegade replicants (played wonderfully by Rutger Hauer), finally confronts his creator, Dr. Eldon Tyrell, on the subject of Batty’s impending demise. Tyrell asks him what he wants, and in the previous versions that I’ve seen, Batty responds with the classic line, “I want more life, fucker.”

Hauer had intentionally tried to pronounce “fucker” so that it sounded like a blend of “fucker” and “father” — perhaps to communicate the conflict that Batty experiences upon seeing his creator — but it’s more the former than the latter.

In the “Final Cut” version, however, the line has been changed to “I want more life, father.” And while the new line is perhaps a bit more correct with regards to Batty’s relationship to Tyrell, part me does like the attempt at ambiguity in the former line, as well as its darker, more sinister overtones. After all, this is the scene where Batty — confused and enraged by his fate and his helplessness to change it — lashes out at his creator, and ultimately kills the source of both his creation and damnation.

(On a sidenote, this scene is especially beautiful from a visual standpoint. It takes place in Tyrell’s office/bedchamber, which looks positively cathedral-like. Tyrell is dressed in a luxurious white robe that has monastic/papal look to it whereas Batty is wearing black leather. Tyrell is small and thin, with perfectly styled black hair; Batty is large and imposing, with a shock of bleached white hair. Tyrell wears thick glasses that distort his eyes; Batty’s eyes are crystal clear blue, and always looking around. Small details, perhaps, but nevertheless fascinating to watch and think about.)

Time to die…

The second difference occurs at the end of the movie, when Batty gives his moving “tears in rain” speech and finally dies before a bewildered Deckard (Harrison Ford).

At an earlier point in the film, Batty comes into possession of a dove, which he carries with him in the final chase. When Batty dies, the dove — a rather obvious visual metaphor for Batty’s soul, as well as a symbol of purity and of the Holy Spirit (an intriguing idea given the Christian imagery surrounding Batty in scenes immediately preceding this one) — is released. In the earlier versions of the film, it flies up into a clear blue sky, which is the only time we see anything other than an oppressive, smoke, rain, and pollution-clogged sky.

In the “Final Cut,” though, the dove flies up into a dark sky, which is visually consistent with the rest of the film. But I always appreciated the blue sky imagery. It might’ve been coincidental originally — perhaps Scott was rushed for time and couldn’t do the rainy sky like he had envisioned — but the combination of the dove/soul imagery with the only moment of natural blue sky in the film always struck me as especially beautiful and poignant.

There are other differences between the “Final Cut” and the earlier versions of Blade Runner, but these two are the most significant for me. Like so much else in Blade Runner, I want to ponder these changes, to think about how they might change how I interpret and understand the film. I suppose that’s part of the challenge of watching the director’s definitive vision of a film when previous versions have already become definitive for you.