Some Random Reflections Upon Returning to Middle-earth

I recently checked off a pretty important box on my “Geek Dad” to-do list: introducing our kids to the Lord of the Rings films. Renae and I were initially concerned that A) the films might be too long and involved for our kids and B) some of the scenes, like Aragorn’s duel with Lurtz or the various battle sequences, would be too intense/gory/violent. But after their reactions to Jurassic Park (e.g., laughing when the T-Rex ate the slimy corporate lawyer) assuaged our fears related to “B,” we went all in.

I’m proud (and relieved) to say that, for the most part, our kids enjoyed all three films, though their attention did wander at various points during the 3+ hour runtimes (we watched the Extended editions, natch).

Our oldest especially loved them (they’re officially his favorite films now) and was fascinated by the various themes in Howard Shore’s masterful score. Our middle child was most impressed by Legolas’ action prowess, particularly his elven “shieldboarding” skills. And our youngest cared not for spoilers but always wanted to know who would live and who would die whenever a battle broke out.

More Than Just Movies

It’d been at least a decade since I’d watched any of the Lord of the Rings films in their entirety, and to be honest, I was nervous. I loved these films when they first came out. Watching each new one when it arrived in theaters, followed by watching the Extended editions, became something of a ritual for my friends and I. But would the trilogy still hold up, 10+ years after the fact?

Put simply, it does, absolutely and without a doubt.

Sure, there are some quibbles. Certain effects haven’t aged very well, especially compared to today’s effects-filled spectacles; some of the acting and dialog gets portentous in a way that undermines certain scenes’ emotional heft; and there are moments when director Peter Jackson can’t quite avoid indulging in excess. (Of the three films, The Fellowship of the Ring is my favorite, if only because it’s not filled with quite as much excess as the other two.)

All that being said… I’m not sure when it was — it might’ve been as early as the first time I heard the plaintive “Shire” theme with its melody borrowed from one of my favorite hymns, “This Is My Father’s World” — but at some point, I was clearly reminded that I wasn’t just watching a series of big budget Hollywood spectacles. Oh, these films are certainly that, but they’re also so much more.

The amount of care, detail, energy, passion, and time (almost a decade) that went into the making of these three films was monumental and impossible to not notice in every single frame. And it elevates these films in a way that is unparalleled. Indeed, I doubt we’ll see another cinematic phenomenon quite like it anytime soon.

I Want to Go to There

On several occasions, my wife caught herself thinking “I’d really like to visit there someday” — and I don’t blame her. When production of the films began, Jackson stressed that he wanted to treat J. R. R. Tolkien’s story as an actual historical account. This desire for realism and historicity reveals itself in the intricately detailed costumes, armor, and weapons, the rationales behind the many creature designs, the beautifully realized locations (e.g., the Shire, the Rohan capital of Edoras), and much more. Taken together, they enhance the experience of the films to an incredible degree.

As Stephanie Zacharek wrote in her 2001 review of The Fellowship of the Ring:

This is moviemaking on a grand scale, which is not to say that it’s merely a big, impressive movie. (Any old goat can make one of those.) The crucial distinction is that Jackson’s sense of scale is impeccable. The vistas are huge and wondrous, the special effects sparkling: But Jackson also trains the eye on details that, more than anything else, define the movie’s rich, dreamy look.

The cloaks worn by Frodo and his gang are clasped with delicate green enamel pins in the shape of an art nouveau leaf. As readers of the Tolkien books know, the clasps will ultimately have a special role. Even so, considering that most of us understand the visual shorthand of movie props and costumes, there’s no reason they’d have to be so exquisitely made. As it is, with their tendrils and fragile veins, they look like family heirlooms, and they’re valuable grace notes to the look of the movie.

Several months ago, I wrote about the German term fernweh, which roughly translates as a homesickness for a place you’ve never been or could never travel to. I think that’s as good a description as any for the feeling I get watching Jackson’s films. Yes, they’re exciting, moving, and beautiful to watch, but more than all of that, the effect of seeing all of those “grace notes” fills me with a sense of longing. Again, Zacharek (emphasis mine):

“The Fellowship of the Ring” throws down a daunting challenge to filmmakers everywhere, and even more so to the studios that back them. Audiences deserve the greatest you have in you. If you’ve made money off giving them anything less, it was just dumb luck. From now on, they’ll know they have a right to magic.

For all of their flaws, Jackson’s films should be lauded for this one simple fact: they make you believe in Middle-earth, and all of the magic and wonder that it contains. And to paraphrase Tina Fey, they make you want to go to there with every fiber of your being. And that’s a very fine gift for a film to give you.

For the Cast & Crew

Related to all of that, I wondered about the actors and crew, especially Jackson, and what it must’ve been like to return to “normal” life upon completing the films. They did such an amazing job of creating this whole other world for viewers to enjoy. What was it like, then, for those who made that world, and in a very real sense, inhabited it for months and years on end?

Was it relatively easy to move on to the next gig, or was some period of decompression or even grieving necessary? I know I felt sad when The Return of the King’s credits began to roll; what sort of emotional rollercoaster did the actors experience upon hearing “cut” for the final time?

The various “behind the scenes” features include scenes of people talking about how life-changing and monumental the films were at the time. Do they still feel that way to this day? What goes through the mind of, say, Elijah Wood, Sir Ian McKellen, Sean Astin, Viggo Mortensen, or Liv Tyler when they think about their involvement in the trilogy, nearly two decades after the fact?

The Theology of the Ring

Obviously, one doesn’t need to be a Christian to enjoy these films. But I would argue that being a Christian, or at least having some knowledge of the Christian faith, enhances one’s appreciation of the films’ (and by extension, Tolkien’s) underlying themes.

Tolkien never intended his stories to be mere allegory. In fact, he was opposed to allegory (“I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations,” he once wrote) and found it a poor way to tell stories. And yet, being a devout Catholic, his imagination was almost certainly shaped by Christian theology, and so it’s impossible not to detect certain religious parallels.

As Joseph Pearce wrote in his foreword to Bradley J. Birzer’s J. R. R. Tolkien’s Sanctifying Myth (which is an excellent exploration, by the way, of the series’ religious themes):

Ultimately, The Lord of the Rings is a sublimely mystical Passion Play. The carrying of the Ring — the emblem of Sin — is the Carrying of the Cross. The mythological quest is a veritable Via Dolorosa. Catholic theology, explicitly present in The Silmarillion and implicitly present in The Lord of the Rings, is omnipresent in both, breathing life into the tales as invisibly but as surely as oxygen.

Consider these specific examples:

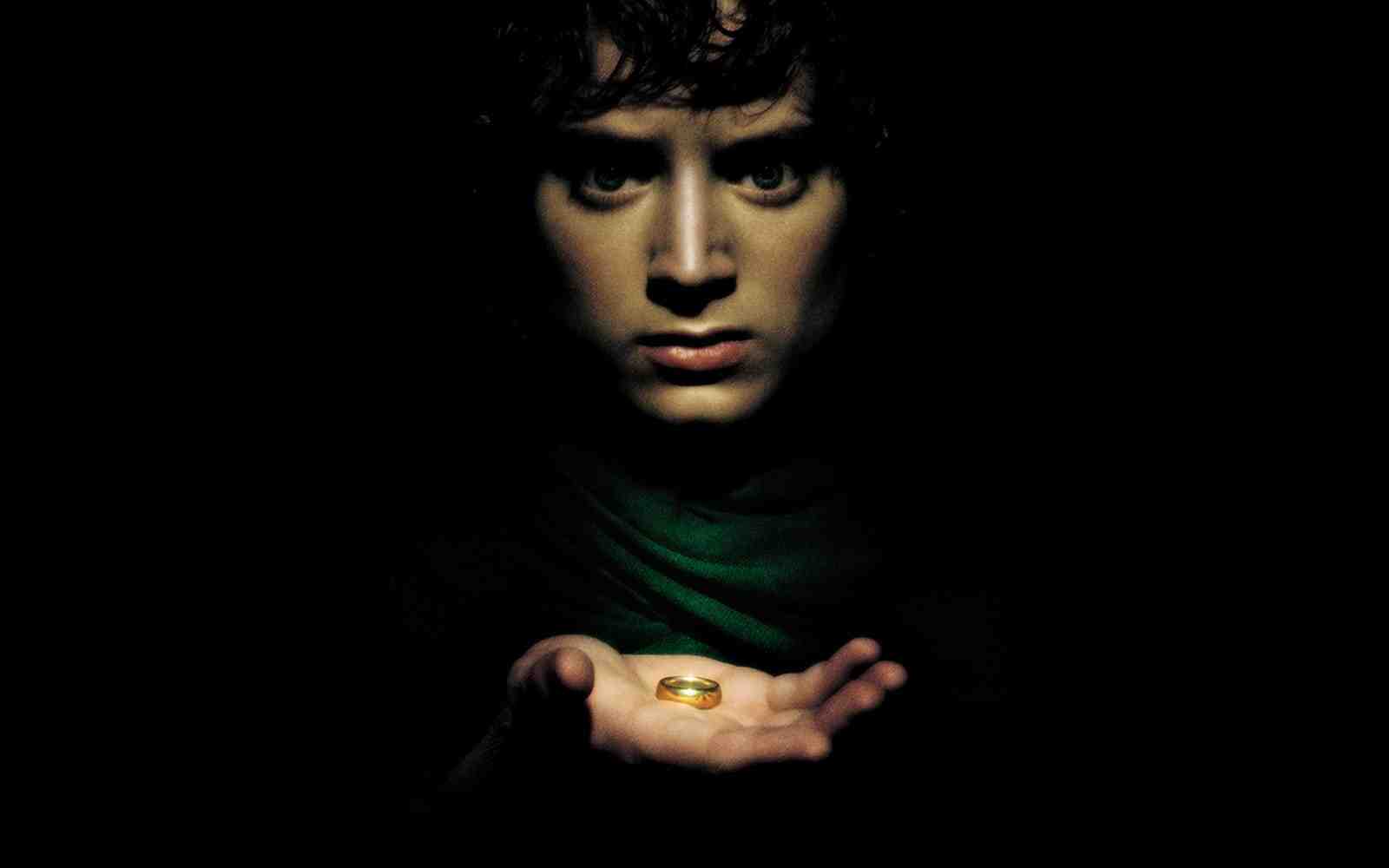

- Frodo, Gandalf, and Aragorn all have Christ-like qualities as (respectively) the suffering servant, the one who sacrifices himself and is resurrected to complete his divinely appointed task, and the rightful king who rules with justice and mercy. Gandalf also has a prophetic, John the Baptist quality as the one who helps pave the way for the rightful king to return.

- The Elvish lembas bread has sustaining qualities à la the host in Catholic theology.

- The One Ring, with its power to tempt, seduce, and twist even the noblest of intentions is one of the best illustrations of the power of sin a pastor could hope for. I still remember the first time I watched Frodo finally give in to the Ring’s power in the heart of Mount Doom. It was so chilling to watch precisely because it was such a strong reminder of how easily I surrender myself to sin even when I know the right that I’m supposed to do.

Even the structure of the Fellowship’s journey has Christian parallels. The Fellowship depart from Rivendell on December 25 and the Ring and Sauron are destroyed on March 25. December 25 is obviously Christmas while March 25 is the Feast of the Annunciation, which celebrates when Christ was conceived, thus ushering in a new age and the redemption of the world.

Again, you don’t need to be a Christian to enjoy the films, as evidenced by their widespread success. But if you are a Christian, then certain characters, scenes, and even lines of dialog take on an added resonance. Gandalf’s speech to Frodo about judgment, mercy, and “other forces at work” in the word, his words of comfort to Merry in Return of the King — these are ultimately nice-sounding platitudes until understood within the context of Tolkien’s Christian imagination, which gives them additional poignancy. (And yes, I know those exact scenes aren’t in the books, but rather, are cobbled together from disparate parts of Tolkien’s writings. Still, I think they offer a nice summation of Tolkien’s beliefs and intent. At the very least, they serve as welcome moments of grace in the movies.)

A Eucatastrophe

More than being awed by the films’ epic scenes and battles — which, I grant you, are pretty awesome — I want my kids (and myself, for that matter), to remember that, yes, The Lord of the Rings is about the need to stand up to evil, to choose loyalty, honor, courage, and conviction over fecklessness and cowardice, no matter the cost.

But above all else, it’s a story about the great power of sin and the equally great need for grace. It is, after all, a eucatastrophe, to use Tolkien’s term: a story in which something spectacularly good happens to the characters even though they have failed and all hope seems lost. (Which, from the Christian perspective, is precisely what Christ’s death and resurrection represents for us all.)

And it is, of course, a reminder to always be as good and loyal a friend as Samwise Gamgee.