The Safe Mediocrity of Christian Art

Growing up as a Christian kid in the late ’80s and early ’90s, there were several things that I feared on an almost existential level.

The first was nuclear armageddon. These were the Cold War’s final years, and I often found myself contemplating Russian ICBMs striking the U.S. I wouldn’t have suffered much in any such attack; we didn’t live too far from Offutt Air Force Base, which was sure to be a primary target. But my friends and family members in other parts of the country? Their fates were less certain but bound to be more horrific.

The second was the Rapture, which was closely tied to the first, since Russian activity was often seen as fulfilling biblical prophecy. It wasn’t Jesus’ return that scared me. Rather, I was terrified of being “left behind.” If I couldn’t find my parents in the grocery store or woke up in a seemingly empty house, my mind immediately assumed that the rest of my family had been caught up by the Spirit and were now enjoying paradise while I was doomed to face the Great Tribulation and the Antichrist. I’d eventually discover that dispensational premillenialism was not the Church’s only eschatological framework, but to this day, I still have the occasional “Rapture moment.”

Finally, there was spiritual warfare, or the idea that an invisible battle raged between demonic entities and heavenly forces, with the souls of every human being in the balance. Now this, I still believe, though I now understand spiritual warfare to be far more complicated. Back then, however, spiritual warfare was both simpler and more lurid.

Simpler in that it was “obvious” where demonic activity could be found (e.g., Hollywood, liberal politics, the “New Age” movement). And lurid because this was at the height of the “satanic panic,” with its suspicions of widespread-yet-secret cult activity, including virgin and infant sacrifice, and larger-than-life personalities like Bob Larson and the discredited Mike Warnke fanning the flames. (Oh, and rumors that Procter & Gamble was a front for the Church of Satan.)

This stuff fascinated me, not because I found it attractive or had any desire to join a satanic cult, but because it seemed so far removed from the safe reality of my middle-class environment. I felt compelled to determine its veracity for myself. The same could be said for all of those books and movies I saw about the evils of rock n’ roll. They only made me more interested in rock n’ roll, not because I wanted to be rebellious, but because the allegations seemed so over-the-top as to be impossible; there was no way they could all be true. (Of course, plenty of them were true. As a whole, rock musicians aren’t exactly known for asceticism and responsible living.)

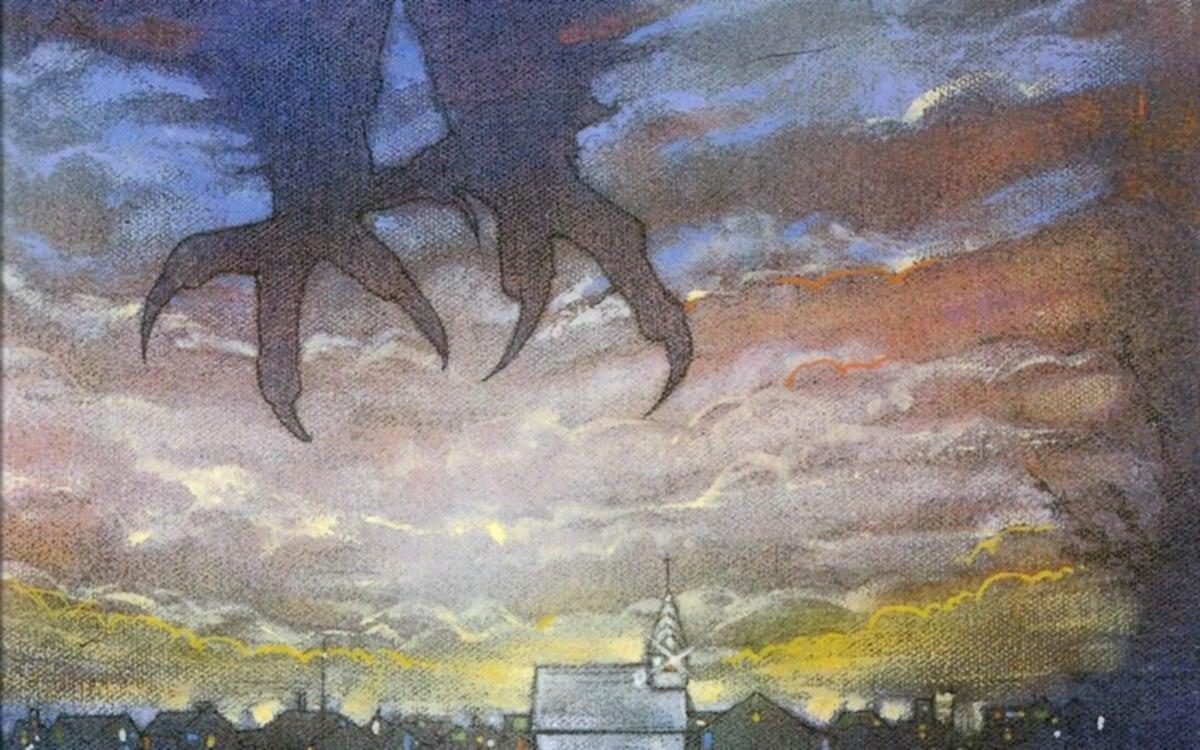

It was during this tumultuous, fearful time that I read Frank Peretti’s debut novel, This Present Darkness, after hearing another kid in my youth group rave about it. Its tale of angels, demons, beleaguered Christians, and sinister New Age organizations tapped directly into the zeitgeist — and I loved it.

Peretti’s novel lifted the concept of spiritual warfare out of the Bible’s pages and made it seem so much more real and vital to my middle school imagination. What’s more, it made spiritual warfare seem totally awesome, as angels with names like Tal and Guilo kicked demon butt one page after another. This Present Darkness felt like a Hollywood action movie or superhero comic but only better, because it was, y’know, Christian. (I’m not the only one who felt this way: the novel remained on Christian bestseller lists for almost three years and has sold 2.5 million copies to date.)

Suffice to say, I was already predisposed to Justin Lee’s analysis of This Present Darkness before even reading it, and it did not disappoint. Admittedly, this was due in part to nostalgia. Lee’s description of his childhood “garden-variety Evangelical” church — and his fears as a young Christian — paralleled my own childhood memories and anxieties.

But to its credit, Lee’s article moves beyond mere nostalgia to an insightful examination of how Christians often use storytelling, not as art but rather as something more akin to propaganda. In the process, they deliver material that entertains the base but ultimately rings false (emphasis mine):

It should surprise no one that American Evangelicals treated the Darkness books as spiritual manuals. The Evangelical struggle against reading fiction as fiction is as old as, well, Evangelicalism. “Evangelicals retain an old, mid-19th-century understanding of fiction as a utilitarian instrument,” James Van Wyck, a literary historian specializing in nineteenth-century Evangelicalism, observes. “A work of fiction does something to you. They want fiction to make you think right, feel right, and act right — to guide you on your pilgrimage to heaven.” For today’s Evangelicals — no less than those of the mid-nineteenth century — fiction is written and read for the emotional inculcation of propositional truths. The clearer the message, the more valuable the novel.

This ethic of reading affects the kind of writing Evangelicals do. “We Christian novelists have a strange advantage in the Christian market,” says Peretti. “We don’t have to be good writers necessarily as long as our message is firm and clear.” In This Present Darkness the effort to accommodate “Christian” sensibilities yields absurdities like a hardboiled, not-yet-Christian reporter who doesn’t cuss, and incarcerated hookers who talk like Victorian schoolmarms. Much worse, it prevents the depiction of serious, true-to-life battles with sin. When the pastor-hero is tempted to adultery by a woman in his congregation, we’re given no interiority and no physical details that depict him as actually tempted. The admirable desire to avoid tempting the reader comes at a literary cost.

[…]

Peretti’s art fails, and it does so for the simple reason that his representations of angels and demons are not strange enough. His novels just aren’t scary because they fail to be true to the irreducible particularity of human life, which means we don’t see the dangers as real. In the end, readers are left only with what propositional meanings can be gleaned from the surface. They’re left with “Strategic Level Spiritual Warfare” and a somewhat muted sense of their own culpability in sin. Horror and temptation are made manageable with certain techniques.

Denis Haack gave a presentation several years ago that pointed out how art can fail to portray life truthfully. (Though Haack’s presentation focused on film, his observations apply just as well to literature.) For Christian artists, this can resemble presenting a “safe” (i.e., neutered) version of reality so as not to place stumbling blocks before fellow believers. As laudable as this impulse may be, it can result in depicting people in ways that don’t resemble actual human beings.

As a result, such art lacks a sense of evil because the villains aren’t really villainous, since to show truly villainous behavior might hurt a fellow Christian’s faith or challenge their convictions. Subsequently, the heroes don’t really seem heroic since their faith is never seen being tested by sin and depravity, again so as not to cause a Christian brother or sister to stumble. (The point here isn’t to say that Christian artists should feel license to make gratuitous or exploitative art. Rather, they should focus on making honest art.)

Furthermore, because the artists are fellow Christians, their art is often given a handicap. It doesn’t matter if said art is any good — if it’s well-written, well-produced, imaginative, etc. All that matters is that the artist’s heart is in the right place, their art is for the Lord, they’re trying to win souls for Christ, and so on. Therefore, normal criticism shouldn’t apply. (Or as Peretti put it, Christian artists “don’t have to be good… as long as our message is firm and clear.”) Under this rubric, to be critical of such art is to be uncharitable, since you’re essentially denigrating someone else’s ministry and soul-saving efforts.

Of course, such handicaps don’t apply to other fields and professions. Consider a chef who has devoted their cooking to the Lord. At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter how fervent or authentic their witness may be; their food still needs to be delicious and filling (subjective tastes and preferences notwithstanding). It doesn’t matter how strong and faithful a Christian they are, they can still be a terrible chef who makes disgusting food.

One would think that Christian artists would want to strive to be the best at their art, and not simply coast by on religious nepotism or because they don’t rock the boat, theologically speaking. They would want to be more than simply theologically correct; they would want to be the most imaginative writers, the most thoughtful poets, the most daring painters, the most visually arresting filmmakers, the most evocative songwriters and composers. Because after all, they realize that their talents originate from, and are ultimately worship offered to, the greatest and most sublime Artist of all.

The Church’s lax approach to art, and specifically, its willingness to promote substandard work for no other reason than because it was made by Christians — while simultaneously dismissing skillful, beautiful, and thoughtful art for no other reason than because it was made by non-Christians — has harmed its witness. Of this I am convinced. It’s scared and denigrated countless talented individuals, refused to engage with truth and beauty found outside narrow theological understandings, and perhaps worst of all, watered down the Gospel itself.

I experienced this primarily with music as a high schooler going through all of the usual angst and tumult of that age. My youth group peers were listening to bright, shiny, polished Christian pop music that checked all of the right theological boxes. CCM artists sang about Jesus in nearly every song and thanked Him effusively in the liner notes, but the clean, upbeat reality contained within their music felt alien to me.

I was that kid in church who preferred to read Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, and Psalm 88, and so I gravitated to the music of Robert Smith, Ian Curtis, Trent Reznor, and David Gahan. I knew they weren’t Christian, and in some cases, were explicitly anti-Christian, but at the same time, their music was unafraid to acknowledge darkness, sorrow, and brokenness. Listening to those artists wasn’t some childish act of rebellion against my church upbringing so much as a search for comfort, compassion, and understanding. Their music was most definitely not theologically correct, but at least it felt more honest than much of the “truth-filled” music I heard in my church.

I would eventually discover Christian artists who were similarly unafraid to write songs that explored darkness and doubt. Artists like The Violet Burning, Michael Knott, The Prayer Chain, Mortal, and Circle of Dust not only wrote great songs, but they were proof to me that one could praise God with your art and still not shy away from the more difficult aspects of life — that indeed, you could bring honor to God by being honest about life, warts and all.

This may not sound like much to you. But growing up in a relatively insular church environment where, in hindsight, much of my life was driven by fear (though to be clear, I’m thankful for much of my church upbringing and realize I had it better than so many others), it was a revelatory understanding.

These days, I look back on many of the artifacts of my Christian youth — premillennialism and This Present Darkness’ vision of spiritual warfare included — with a mix of bemusement, criticism, and yes, even gratitude. I’m thankful that I’ve moved past them (the occasional “Rapture moment” notwithstanding) even as I acknowledge the good things about my church upbringing. Still, I do wonder about those who haven’t been able to do so. How many lost their faith, found it deadened, or simply concluded that faith was irrelevant because of the Church’s timid and short-sighted approach to art, creativity, and honesty concerning the complexities of life this side of eternity?