Revisiting Some Classic Choose Your Own Adventure Books

Like many parents, Edward Packard told his kids bedtime stories. One night, though, he ran out of ideas for the story he was telling and asked his two daughters what should happen next. Packard then came up with original endings based on their ideas. Inspired by his kids’ enthusiastic response to this interactive approach to storytelling, Packard decided to write a book in which the reader was the “star” of the story, and could experience multiple plots and endings based on their choices.

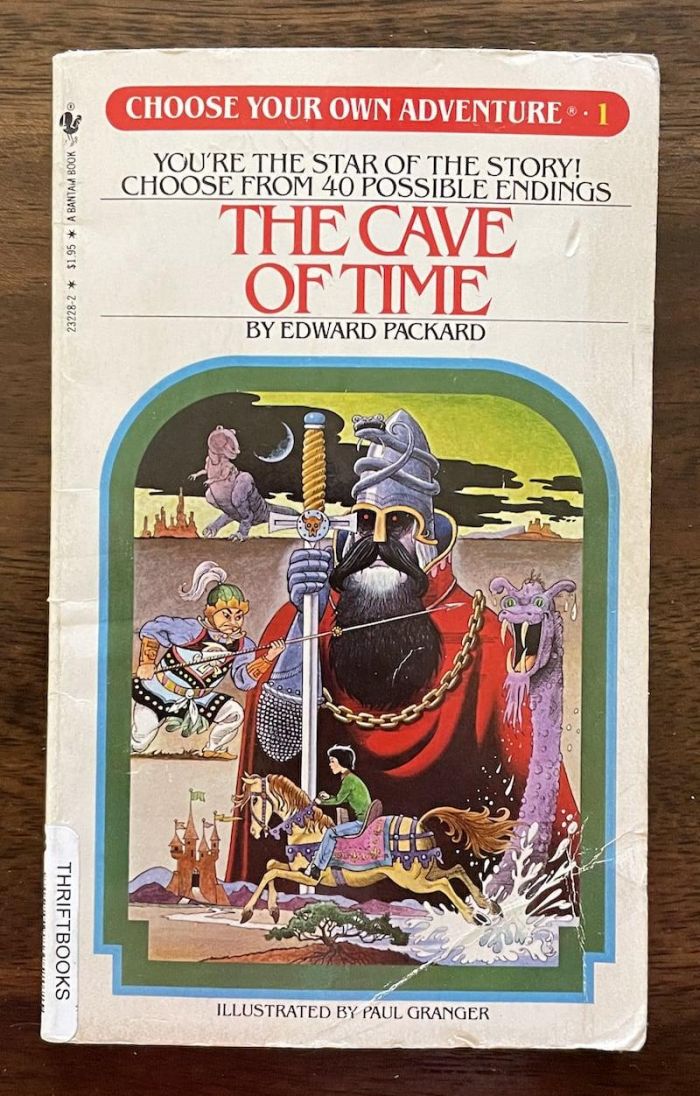

In 1969, Packard wrote The Adventures of You on Sugarcane Island. Though initially passed over by several publishers, Sugarcane Island was eventually published in 1976 by Vermont Crossroads Press, which sold 8,000 copies of the book. Packard wrote several more books in the same vein, and in 1979, Bantam Books published the first official Choose Your Own Adventure title: Packard’s The Cave of Time. Packard would eventually write over seventy CYOA books, with the rest written by a variety of authors including R. A. Montgomery, Julius Goodman, Louise Munro Foley, and Packard’s own daughter, Andrea.

The original CYOA line ran from 1979 – 1998, and contains almost 200 books that span genres including fantasy, sci-fi, horror, sports, martial arts, and espionage. It was a massive success, selling over 250 million copies and inspiring additional lines. Some of these new lines were geared towards specific audiences (like younger readers) or were serialized (like Packard’s Space Hawks titles) while others were branded with Disney and Star Wars.

The CYOA license is currently owned by R. A. Montgomery’s Chooseco, which continues to publish new titles (like the upcoming The Flight of the Unicorn) as well as republish classic CYOA titles. As for Packard, he’s published additional titles under his own U-Ventures imprint and in 2020, released an interactive audio version of Journey to the Year 3000.

Around 4th or 5th grade, I became obsessed with the CYOA books. Aside from my family’s encyclopedias, they might’ve been the only books that I read on a regular basis at that age. My classmates and I would discuss our favorite titles, exchange tips on how to get to the “best” endings, and share our favorite endings.

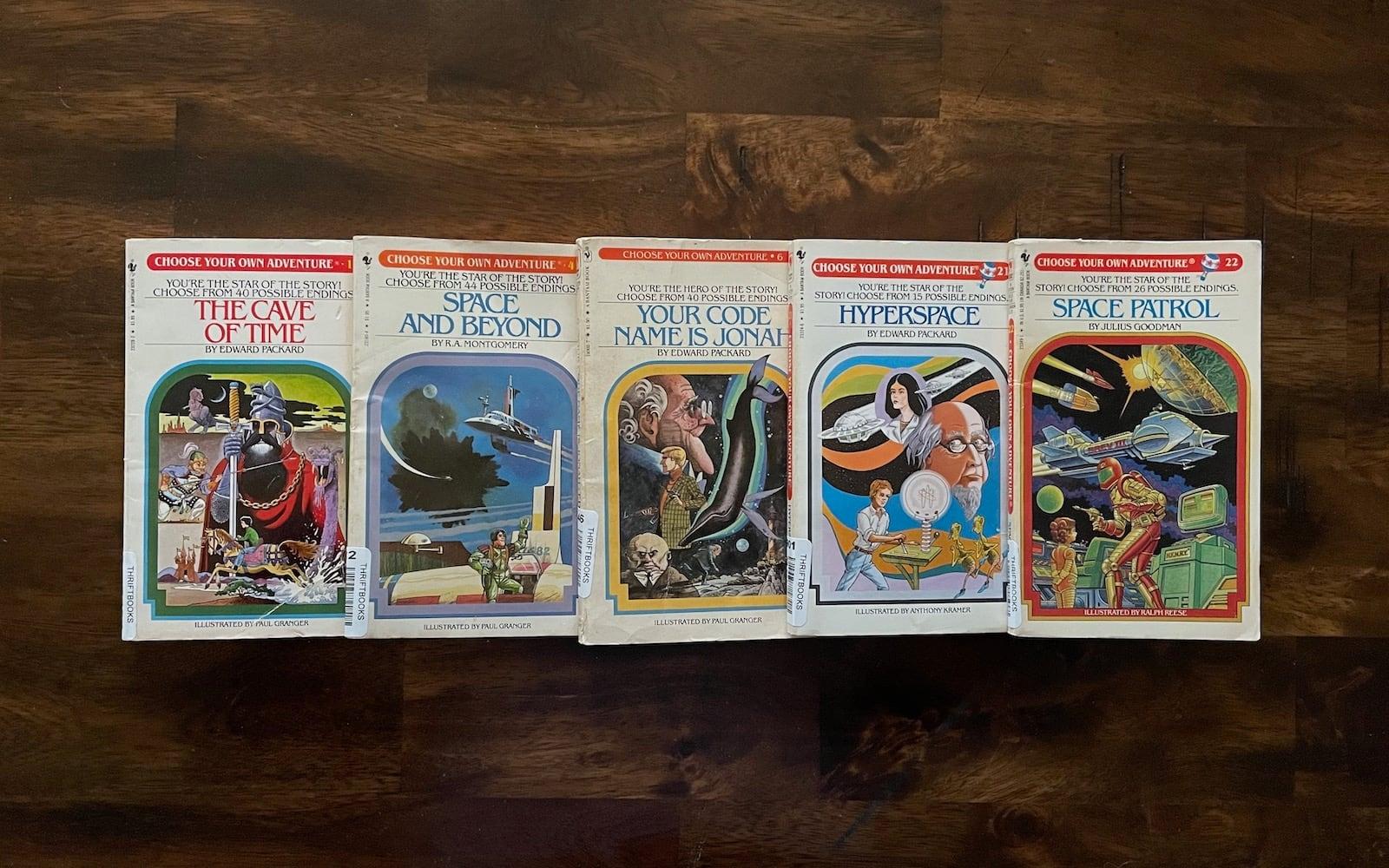

I haven’t thought about CYOA books in years, if not decades, but earlier this month, I found a bunch for sale on Thriftbooks (our family’s favorite online bookseller, and yes, that is a referral link). I ended up buying a handful of them:

- The Cave of Time (#1, Edward Packard, 1979)

- Space and Beyond (#4, R. A. Montgomery, 1980)

- Your Code Name Is Jonah (#6, Edward Packard, 1980)

- Hyperspace (#21, Edward Packard, 1983)

- Space Patrol (#22, Julius Goodman, 1983)

I specifically remember Your Code Name Is Jonah and Space Patrol being two of my favorites. As for the others, I bought them because of their historical significance (as in the case of The Cave of Time) or because they just sounded kind of neat. In any case, I won’t deny that nostalgia played a huge factor in my purchasing decision. Even just looking at their vivid cover artwork is enough to take me back to the hours I spent perusing the shelves at Omaha’s Millard Branch library.

But nostalgia aside, I was pleasantly surprised to find them, on the whole, pretty engaging even after all this time. The CYOA format might seem like it could be rather gimmicky or confusing, but it really does make for a fun and clever experience that’s more akin to a game than a “normal” book. Or as Sam Kabo Ashwell describes it in his analysis of The Cave of Time:

There’s something appealing about the haphazard naivite of the design. The book’s organisation is not random — often nodes around the same twig will have adjacent or close numbers, so that it’s easy to sneak a peek at alternative options. It’s not obvious whether this is accidental (it’s the sort of thing that would happen if you were picking numbers in the order of writing) or a small kindness, giving the player room to pick a better path. But it captures — in a way that can’t really be done in static fiction — the exhilarating open structure of games of make-believe, one of the most powerful underliers of fiction and games.

Also, I’m pretty sure you could write an entire college thesis on how the CYOA books’ interactive, non-linear nature — which strongly encourages you to keep multiple pages bookmarked as you jump back and forth between storylines or even read multiple storylines in parallel — primed an entire generation for the interactive, non-linear nature of the World Wide Web. (There are also obvious parallels to the decision-making processes that appear in so many video games these days, and are starting to emerge in other media, e.g., Netflix’s Black Mirror: Bandersnatch.)

Of the five books I bought, I enjoyed the three Packard books most. (Which shouldn’t be too surprising, given that he started the whole thing.) The Cave of Time finds you tumbling back and forth through time as you explore the titular cave. One minute, you’re encountering knights and trying to avoid the castle prison, the next, you’re running from woolly mammoths, hanging out with Abraham Lincoln as he writes the Gettysburg Address, or flung into the distant future where the sun’s dying.

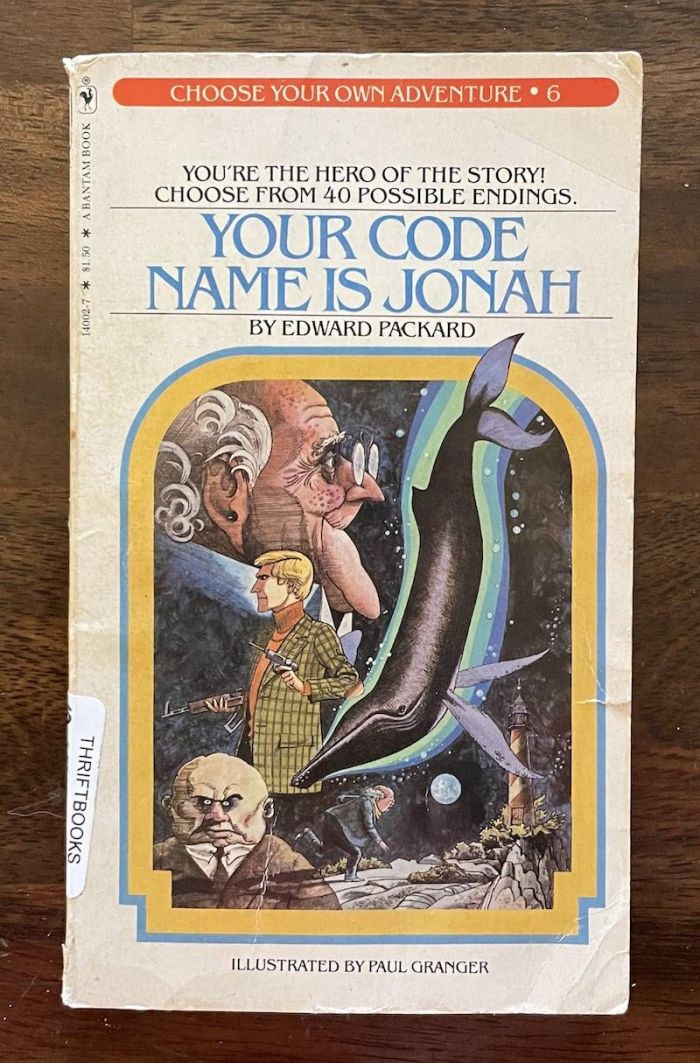

Your Code Name Is Jonah is a Cold War spy tale mixed with some nascent environmental themes. As a secret agent with the Special Intelligence Group, you must track down a missing scientist and determine the meaning of a newly recorded humpback whale song before the Russians do. As befitting a 007-esque spy tale, you’ve got an arsenal of cool gadgets and weapons, there are dangerous car chases, and you’ll probably be double-crossed at least once.

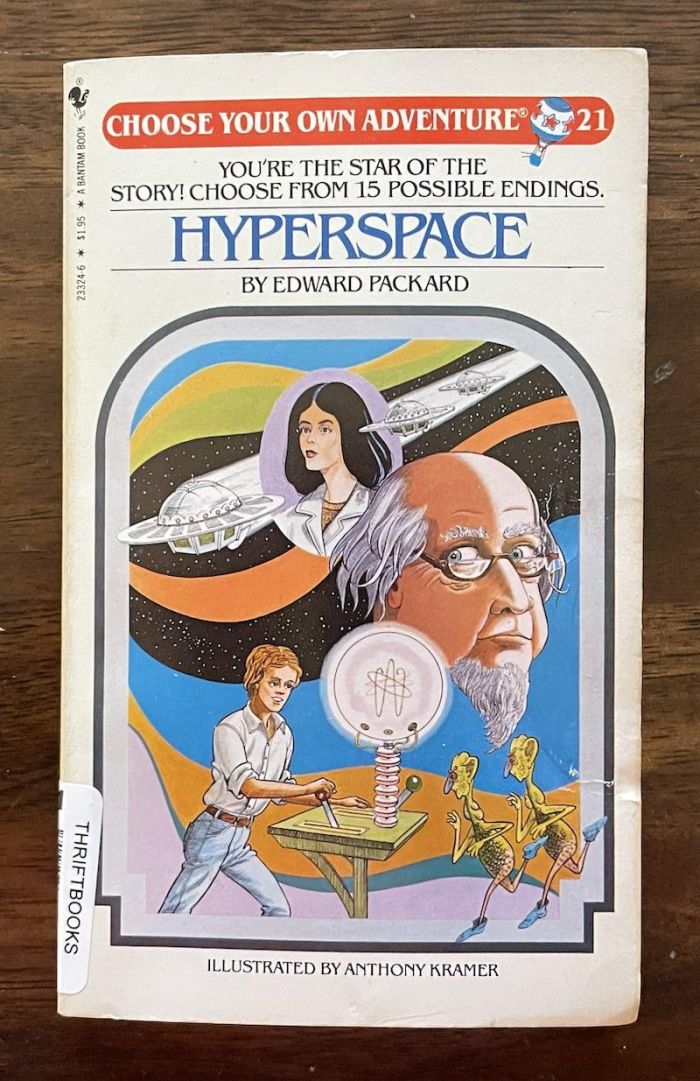

Finally, there’s Hyperspace. All of the CYOA books begin with a warning against reading them straight through that also highlights the consequences of the reader’s actions: “Think carefully before you make a move! One mistake can be your last… or it may lead you to fame and fortune!” Hyperspace, however, comes with an additional warning that what you’re about to read isn’t just another CYOA book. Indeed, Hyperspace feels like Packard’s attempt to push the CYOA format to its limits.

The book begins with you meeting your next door neighbor, a brilliant scientist who’s invented a device capable of accessing hyperspace, a multi-dimensional space that connects your universe to countless others where anything’s possible. Which means that as you skip around Hyperspace’s pages, things get increasingly meta. You might meet your doppelgänger from another universe or become the figment of someone else’s imagination. You might read a CYOA book-within-a-book that’s also titled Hyperspace, encounter familiar faces from other CYOA books, or even meet Edward Packard himself.

Much like the CYOA format in general, this sort of extra-meta, winking-and-nodding at the audience could be cheesy. But I really enjoyed it, in part because it feels rather subversive of Packard to take such an approach in a book aimed squarely at grade schoolers. In other words, Hyperspace might’ve been some 5th grader’s first exposure to postmodern metafiction. I don’t recall reading Hyperspace as a kid, but if I had, I probably would’ve dismissed it as being too weird. Or, it might very well have blown my young mind.

Speaking of subversive, one of the things I love most about these CYOA books is just how twisted the “bad” endings can get. While you inherently want to reach a “good” ending — e.g., arriving safely back in your own time or universe, deciphering the humpback whales’ message — the “bad” endings are just as entertaining to read. And doubly so when you consider they were intended for pre-teens.

(Related: You Chose Wrong collects the “bad” endings from numerous CYOA and similar books. Some of them are practically works of art. Others are much more disturbing. I love them all.)

The “bad” endings in Your Code Name Is Jonah are the most straightforwardly violent, e.g., getting shot by KGB agents. But you might also get run over by a Russian sub, drown in the ocean, or even get fired for failing to carry out your duties. The Cave of Time’s “bad” endings are a bit more creative, including being eaten by the Loch Ness Monster. My favorite involves you trying, and failing, to ride a woolly mammoth, and your remains being discovered thousands of years later by the famous paleontologist Dr. Carleton Frisbee — who is subsequently “amazed at how closely you resemble a twentieth-century human being.”

Julius Goodman’s Space Patrol also has some pretty crazy endings. Being that you’re a space cop, some of them just involve being shot by space pirates or getting vaporized in space. But in one storyline, you encounter some advanced alien technology that expands your consciousness. If you choose to share your newfound wisdom with humanity, you end up brain-wiped and farming beans on the moon. (Goodman apparently thought this ending was too bleak, though, because he offers a way out — if you want it. You can unlock your previous memories through meditation, at which point your mind transcends your body and joins with the aliens.)

Not surprisingly, Hyperspace has the trippiest endings, be they “good” or “bad.” Sometimes, the endings are abrupt, e.g., you realize that, as a character in a book, the best way to avoid a terrible fate is to simply stop reading. In one “bad” ending, a hostile universe begins leaking into your own thanks to the scientist’s device, dissolving everything into dust. My favorite ending occurs after you meet Packard, and the world begins to fall apart around you. Packard seems to die but you find yourself traveling into the sixth dimension. Just as you arrive, however, you’re told that “[u]nfortunately, the author of this book, Edward Packard, never made it to the sixth dimension. For that reason he is unable to describe it. Maybe you can, or maybe it can never be described at all.”

Had my parents and teachers known that the CYOA books contained such… bizarre fates, I suspect they might have been less inclined to let me read so many. (Although the books have been widely praised, they have also received some criticism for their violent content, as seen in this 1986 newspaper article.) Of course, one could argue that CYOA books were just following in the footsteps of classic myths and fairy tales, many of which also contain some pretty grim material.

The danger with revisiting treasured childhood icons is that your nostalgic memories may be way better than the reality. (I’m looking in your general direction, Airwolf.) But to my delight, the Choose Your Own Adventure books hold up pretty well. If nothing else, they make for a welcome diversion on a lazy afternoon, which is all I could ask for. Needless to say, I’ll probably be adding to my collection via Thriftbooks while encouraging my own kids to read them.

I do wonder how these books shaped me as a child, though. What role did they play in me becoming who I am today? There are obvious parallels between their non-linear storytelling and the nature of the Web, so perhaps they helped prepare me to become a web developer.

And what of the endings, specifically the “bad” ones? Reading them now, they seem so contra to what’s usually deemed “acceptable” for kids. How did reading subversive, or even just dark, endings like those in Your Code Name Is Jonah color my adult perspective? Do they help explain why I’m drawn to dark humor or appreciate art that isn’t afraid to verge on the transgressive?

One could obviously spend hours discussing and contemplating such things — if one were prone to navel-gazing, that is. But for now, I’m just choosing to be thankful that these books remain a delight, even decades after their original release. That’s as good an ending as I could’ve hoped for.