Outrageous Offense: Pillars of Eternity and the Possibility of Grace

Back in 2008, the original Mass Effect video game came under fire from conservative groups for including some sexual content. While not the first game to feature such content, the response to this particular game was quite interesting, if only for its intensity. For example, columnist Kevin McCullough claimed that Mass Effect could be “customized to sodomize whatever, whoever, however, the game player wishes.”

Critics of the critics responded that the sexual content was optional; the player’s choices in the game determined whether they encountered it or not, and it could be avoided altogether. In addition, the scene was far less graphic than critics indicated. (One Mass Effect critic, Cooper Lawrence, reversed her position and stated that she’d seen more graphic Lost episodes.)

The Mass Effect controversy was noteworthy for several reasons. First, when compared to the reality of the content in question, the outcry seemed pretty disproportionate. Second, it threw into sharp relief the amount of scrutiny being applied to video games; now, even the smallest, most insignificant bit of content had the potential to create a commotion.

Of course, there’s nothing inherently wrong with increased scrutiny. As the video game medium matures and the gaming population diversifies, heightened scrutiny is inevitable — which can be a good thing as it shines light on potential blind spots, challenges assumptions, and leads to more varied and unique gaming experiences. It can also, however, stir up new, perplexing controversies. Which brings us to Pillars of Eternity and the recent controversy surrounding… a poem.

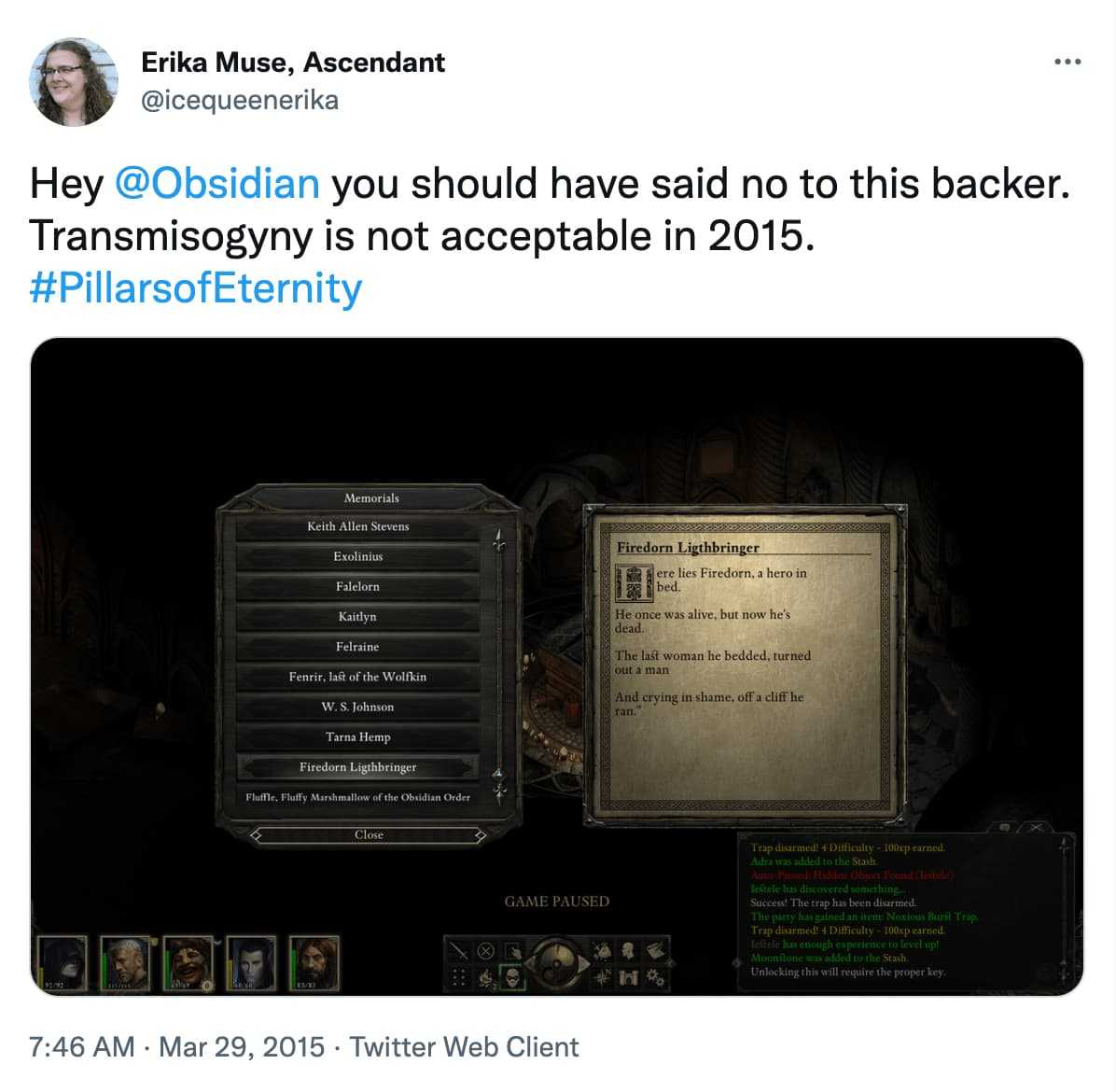

Obsidian’s Pillars of Eternity is a critically acclaimed role-playing game in the vein of such old school classics as Baldur’s Gate. Funded by an incredibly successful Kickstarter campaign (to the tune of nearly $4 million), Pillars of Eternity’s developers offered numerous rewards to their Kickstarter backers, such as being able to contribute content to the game. This led to the inclusion of a poem concerning the “tragic” fate of a character named Firedorn:

Here lies Firedorn, a hero in bed.

He once was alive, but now he’s dead.

The last woman he bedded, turned out a man

And crying in shame, off a cliff he ran.

This content is not critical to the game, but rather, a random piece of text on a gravestone. (For what it’s worth, I recently started playing the game and have yet to find it.) However, some were offended by the poem, calling it transmisogynistic and claiming it perpetuated fears about transgendered people. The criticism was spearheaded by self-described transfeminist Erika Victorious, who tweeted:

Others soon chimed in, with some agreeing with Victorious and others crying foul and claiming that — like Mass Effect’s sex scene — the poem was inconsequential, avoidable, not representative of the game as a whole, just a joke, and so on. Eventually, Obsidian weighed in, stating that the poem had made it into the game without proper vetting and that the backer had supplied some replacement content.

In the case of this specific content, we checked with the backer who wrote it and asked them about changing it. We respect our backers greatly, and felt it was our duty to include them in the process. They gave us new content which we have used to replace what is in the game. To be clear, we followed the process we would have followed had this content been vetted prior to the release of the product.

So now, if you find Firedorn’s grave, you’ll see a new epitaph:

Here lies Firedorn, a bard, a poet

He was also a card, but most didn’t know it

A poem he wrote in jest was misread

They asked for blood, so now he’s just dead

While Erika Victorious appreciated Obsidian’s efforts, there were many who saw Obsidian’s decision as caving to “social justice warriors” and political correctness run amok. Consider this sampling of comments on Kotaku’s article covering the situation:

- “Thank god this absolute travesty was righted. I can go back to finding the next thing to be insulted and triggered by.” (nolansleftnut)

- “Oh no! what are we going to do, someone made a trans joke, the world is going to end with every special snowflake getting triggered.” (Fobhopper)

- “Congratulations to the eternally offended. A joke that languished in obscurity is now in front of millions of extra eyeballs. Mission accomplished?” (Tuhalu)

The most interesting response to the Firedorn controversy, however, came from Firedorn himself, who claimed that the original poem was actually a caricature of individuals who might be offended by transgender people, and was not intended to be transmisogynistic at all.

Firedorn is a character. A fictional character. He’s a creation based on a combination of different people I’ve seen in my life. He’s overly macho, making up for his other shortcomings. Talks a whole lot but doesn’t say much. He’s a womanizer, an alcoholic and he’s not too bright. He’s also has self-esteem issues, which is why he over compensates by being overly sexual. Incidentally, he believes that being with a man will somehow make him a lesser man. You know the type of person I’m referring to. You’ve seen him. You probably even know him, or someone like him. I’ve crossed paths with people like him, numerous times in my life.

[…]

To anyone how was offended by this, I sincerely apologize. My intent was to ridicule the perpetrators of such behavior and not offend its victims. Any form of artistic expression leaves a lot to interpretation and is entirely subjective. But extrapolating any intent from a short limerick and crying in outrage is not the way to go about any of the struggles these victims face. Laugh at Firedorn’s misfortune, his idiocy, his stupidity and narrow mindedness instead.

I’ve emphasized a particularly interesting part in Firedorn’s statement. We live in a hyper-critical age where it often feels like even the slightest statement or action is being weighed and measured to see if it is, in any way, offensive or triggering for anyone, anywhere.

Don’t believe me? Consider the outcry over Trevor Noah’s tweets. Or the pizza place that stated they wouldn’t cater a gay wedding. Or the cake place that said they wouldn’t make an anti-gay cake. Or clapping. Or smiling.

This is not to say that all such claims have no merit whatsoever, or that offended folks need to grow a thicker skin and get over whatever’s offending them. At the same time, I must confess that it often feels like guilt is now automatically presumed before innocence. Not only do we assume that something we find offensive, triggering, bigoted, misogynistic (trans or otherwise), or in anyway hurtful was intended as such (and authorial intent be damned); we are also willing to go out of our way to find any offensive thing we can.

The easy Christian response to all of this is to decry the very real absence of grace that permeates our culture — an absence that cuts all ways, regardless of whatever “side” you happen to take on a particular issue. (Note that the Mass Effect controversy began with conservative groups, while more progressive types called out Pillars of Eternity.) It no longer seems to enter our minds to seek the good of those around us — which includes extending grace and giving them the benefit of the doubt. That approach, in fact, now seems inimical to the spirit of the age.

The Internet undoubtedly has something to do with this. While the net opens up avenues of communication, it also shuts many others down and allows communities to grow increasingly insular, leading to an echo chamber effect and decreased exposure to diverse and challenging views. Combine that with the (false) sense of anonymity that permeates Internet activity and the “online disinhibition effect,” and it’s easy to see how the fires get stoked, and nuance and consideration are tossed aside.

Sadly, fixing this isn’t as simple as adjusting Facebook settings or following new folks on Twitter and Tumblr — though that can’t hurt. But it does require stepping outside our insularity. Several years ago, I came across a thought-provoking piece by Julie Goldberg, a left-leaning, pro-choice feminist whose decision to embrace attachment parenting brought her into contact with folks possessing very different political and religious views. And yet, the more time they spent together, the more they came to see shared interests and convictions. She writes:

Many thoughtful, intelligent people with all kinds of spiritual leanings and belief systems, all kinds of opinions about federalism and tax policy and the Constitution, look at our popular culture, our political culture, our food, our lifestyles, the way we use and waste our resources of time, money, and attention, and conclude that something is seriously awry. They want to turn off the noise of what is out there and tune into the music of relationship, of family, of community. They think it might be wiser to create than to consume all the time, to do more with less, to eschew the temptation to entertain ourselves and our kids to death. Whether they start out motivated by environmentalism, religion, Burkeanism, socialism, logic, or just a longing for closeness and connection, many arrive at the same conclusion.

[…]

It’s fascinating that people with such radically opposed points of view, who may have been taught to think of people on the other side of the political or religious fence as stupid, evil, or both, may be raising their young children in nearly identical ways. Can we do anything useful with that common ground? The barriers we’ve built around red and blue, as if these categories were absolute and eternal, prevent sincere dialogue.

On the surface, Goldberg’s attachment parenting discovery has little to do with video games and transmisogyny. However, it has everything to do with decreasing our scrutiny and criticism a bit and increasing our sensitivity — not to those things that we may find legitimately concerning, but rather, to the strangers we pass by every day, either in the real world or the virtual one.

This may be far easier said than done, and admittedly, runs the risk of slipping into platitude, but at least for those of us who are Christians, we are to extend grace, understanding, and even forgiveness to the extent that those things have been extended to us. It’s difficult, requiring a certain dying to ourselves, but what else can help us look past the skepticism, scrutiny, and presumption that defines so much our public discourse?

This entry was originally published on Christ and Pop Culture on .