The Imaginative Worldbuilding of Lancer

Back in June, I contributed to Itch.io’s “Bundle for Racial Justice and Equality.” In return for supporting a couple of good causes (NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Community Bail Fund), people got access to over 1,700 games. While most of the focus was on the bundle’s many video games, including acclaimed titles like Overland and Celeste, I was also excited that it included some tabletop role-playing games, too.

One such game is Massif Press’s Lancer, in which you play a mech pilot thousands of years in the future. While the game had me at “mech pilot” (thanks to years of conditioning by “giant robot” anime like Macross and Patlabor), a perusal of Lancer’s core book reveals a game that’s much deeper and stranger than just piloting a big robot.

Note: This article will focus less on the actual mechanics of playing Lancer or its merits as a game, and instead, focus more on its setting and lore. If you want a full review of Lancer as a game, then a quick Google search will turn up any number of (largely positive) reviews.

The Rise and Fall and Rise of Humanity

Lancer is set in the distant future where humanity has evolved into a highly advanced, post-scarcity society that now encompasses countless worlds and systems. To help establish and sell this concept, writers Miguel Lopez and Tom Parkinson Morgan have created an incredibly detailed timeline for Earth (called “Cradle” in the game) and humanity that spans millennia.

The timeline covers everything: humanity’s first forays into deep space; the massive ecological collapse that nearly devastated Earth; the formation of Union (the massive galactic hegemony overseeing humanity’s affairs and encouraging its spread throughout the galaxy); the vast scientific discoveries that have helped, and threatened, humanity’s endeavors; and much more.

In the game’s setting, the present day is 5,000 years after Union’s formation, which itself occurred 6,000 years after humanity began sending out a series of colony ships to other Earth-like planets. And yet, as the timeline reveals, the same flaws, foibles, and brokenness continue to plague humanity in the form of wars, unrest, inequality, prejudice, and tyranny.

When Lancer begins, Union has undergone a massive reorganization, with the goal of bringing about true equality for all of its citizens while abandoning the “anthrochauvinism” of Union’s previous incarnation. But humanity is diverse, divided among those who live on the wealthy core planets, those who travel the vast interstellar reaches, and those who live on worlds beyond the current boundaries of Union territory. As such, there are many who rankle under Union’s governance, refuse to buy into its seemingly utopian policies, and resist its expansion in their space.

(In Lancer’s parlance, “anthrochauvinism” is a form of “manifest destiny” that believes that, because humanity has survived so much disaster, it’s earned the right to spread throughout the galaxy. Unfortunately, “anthrochauvinism“ ‘s definition of humanity was limited to whatever form it took on Cradle, leading to the oppression, domination, and appropriation of any human culture not fitting that mold.)

If you’re not a sucker for political intrigue, then this aspect of Lancer’s worldbuilding can be a bit overwhelming, especially when Lopez and Morgan get into the various factions within Union, such as The Interstellar, The Fourth Column, and the Verdant Social Arc. And then there’s Union’s labyrinthine bureaucracy, which includes agencies with titles like “Department of Justice and Human Rights,” “Union Bureau of Orbital and Non-Terrestrial Management,” and “Union Omninetwork Bureau,” to name a few.

But as convoluted and overwhelming as these details can get, they really do help sell the complexity and vastness of humanity within Lancer’s universe.

But what about those mechs?!

I know what you’re probably thinking right now: “Enough about government and politics. Tell me about the mechs!” Fair enough. After all, Lancer’s primary selling point is that it’s a mech combat game.

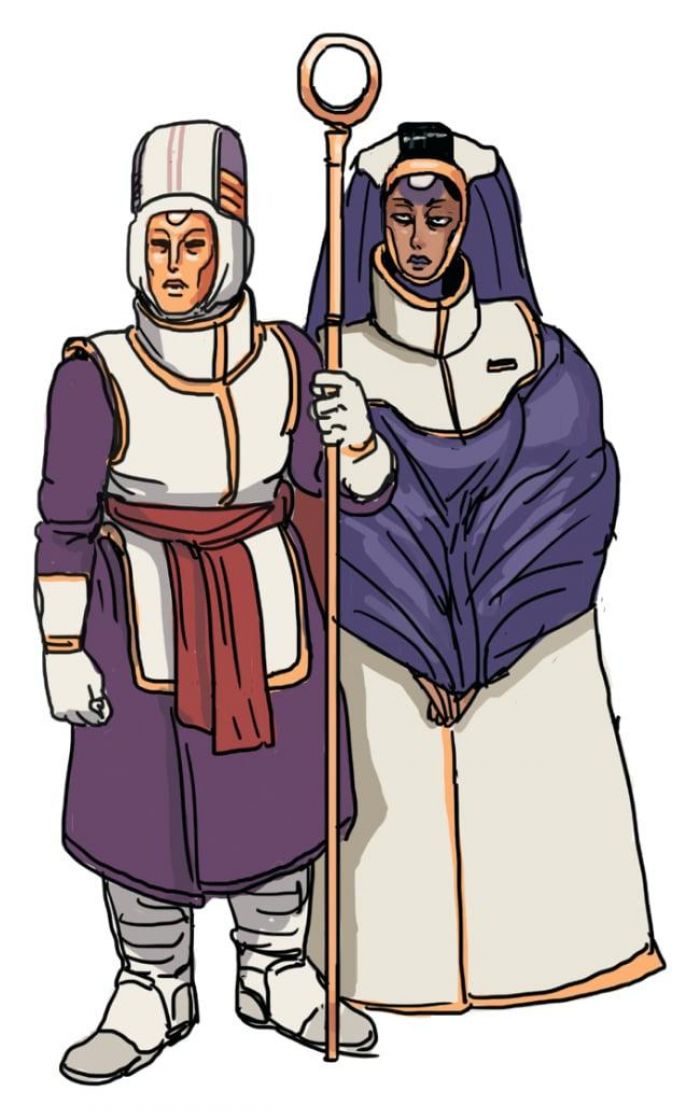

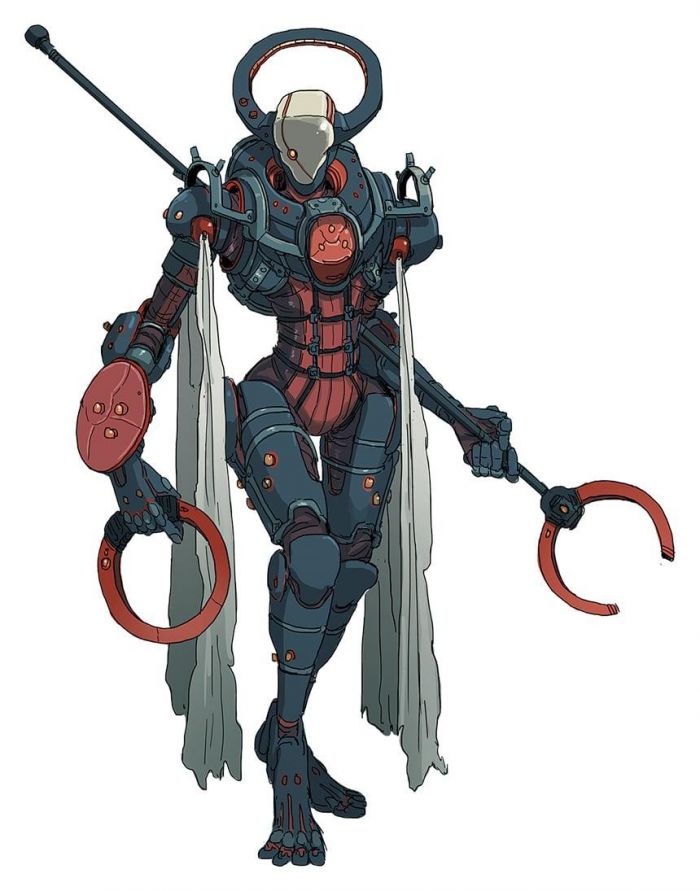

In Lancer’s world, mechs come in all shapes and sizes, from 3 to 15 meters tall, with varying levels of technology, weapons, and even design aesthetics — from blocky, utilitarian behemoths bristling with guns and missiles to mechs that look like something out of Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Just as the game’s writers envisioned a complex, fully-formed history and timeline for Lancer’s setting, so to have they created a similarly complex corporate system to explain the development of Lancer’s many advanced technologies, including mechs. In Lancer’s universe, mechs are licensed and acquired from five massive corporations, all of whom are like empires in their own right vying for dominance (thus adding further intrigue to the game). And as is their wont, the writers have given each company detailed histories, motivations, and goals.

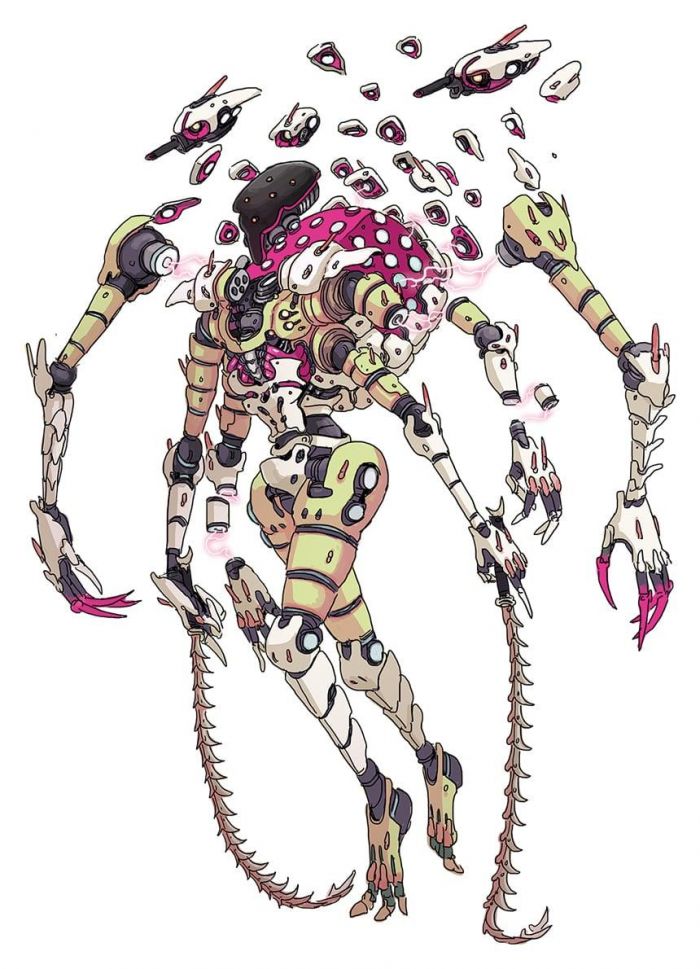

These corporations include: General Massive Systems, one of humanity’s oldest companies and creators of the most ubiquitous mech designs; Smith-Shimano Corpro, who are obsessed with human augmentation and emphasize speed and mobility in their sleek, stylish mechs; and the enigmatic, cult-like Horus, who might have descended from a nigh-omnipotent AI (or might just be from a parallel universe), and whose bizarre-looking mechs incorporate all manner of strange technology.

While mech combat can be nothing more than big robots lobbing missiles at each other, Lancer realizes that warfare ought to look very different thousands of years into the future. Therefore, rather than blast your opponent’s mech with your cannons, it might be better/funner to defeat them by overriding their cognitive abilities with a memetic onslaught, bending probability to your advantage, or slicing them apart with a nanocarbon sword that adapts itself to their strengths.

Furthermore, a Lancer mech is incredibly customizable, assuming its pilot has enough skill and resources to do so. The more powerful a pilot becomes, the more advanced their mech can become, with enhancements including weapons that use gravity or magnetism to crush or trap opponents, nanotech drones, the mech equivalent of brass knuckles, or even a good ol’ fashioned flamethrower.

From Science Fiction to Science Fantasy

Given the far-future setting, Lancer contains body modifications, cybernetic enhancements, and cloning. Artificial intelligence is widespread, too, ranging from incredibly powerful software tools to non-human persons (NHPs), which are sentient entities that are strictly regulated lest they run amok. People can cross vast interstellar distances instantly via blinkspace and everyone is connected by a vast, galaxy-wide computer network called the omninet.

This is all pretty standard sci-fi stuff, but one of my favorite aspects of Lancer’s worldbuilding is that it occasionally shifts from science fiction to science fantasy. While spells and such don’t exist in Lancer, there are phenomena that, for all intents and purposes, are magic-like à la Clarke’s Third Law. While this obviously includes the incredibly advanced technology that makes mechs possible, it primarily focuses on the esoteric field of paracausality (i.e., the study of events and phenomena that exist outside the normal realm of cause and effect).

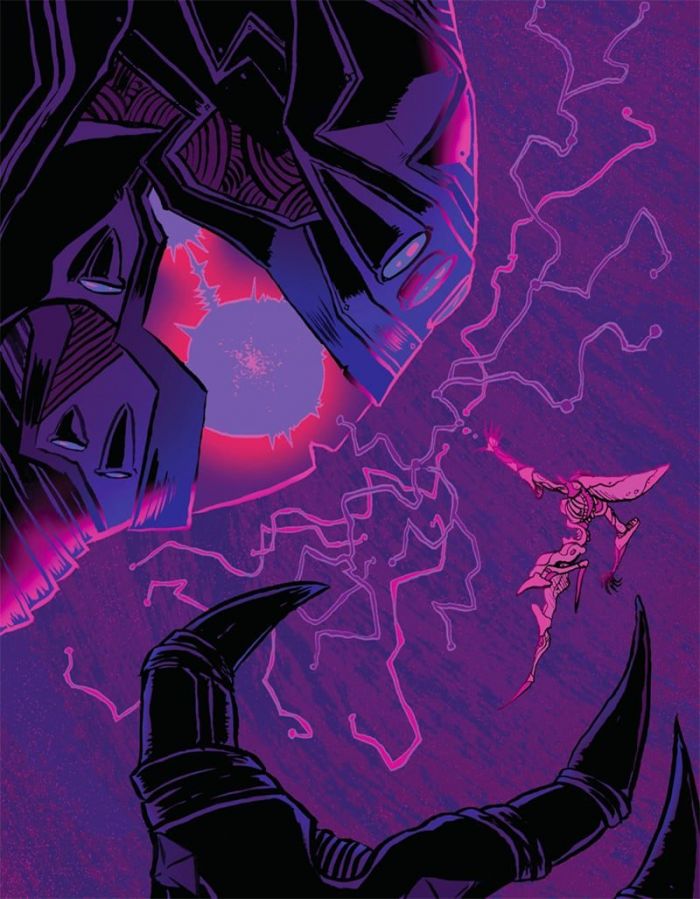

Lancer’s paracausality has its roots in the “Deimos Event,” when a group of powerful AIs used by Union to predict the future inadvertently thought an independent AI named “MONIST-1” into existence about 2,000 years before the game’s “present day.” Or, as the game describes it, “it is possible that one of the [AIs] predicted or discovered MONIST-1 in a parallel simulation, necessitating its existence in our real universe; according to essential-perfect simulation theory, if MONIST-1 exists in one instance, then it must exist across all possible instances of the simulation… This is, understandably, a worrying hypothesis.”

Two years after its “birth,” MONIST-1 takes over the Martian moon Deimos and teleports it through blinkspace to an unknown location. MONIST-1 would return with Deimos two years after that, sowing chaos throughout Union until an agreement concerning AI research was reached. Again, from the core book:

MONIST-1’s speakers directed the course of negotiations while Union’s representatives recorded the entity’s directives. The resultant agreements — the First Contact Accords — were signed following a meeting between delegations from GALSIM and CentComm. Broadly, the Accords laid out the parameters of acceptable exploration for Union; chief among them, a strict denial of any attempt to discover or interact with MONIST-1’s physical form and a blanket prohibition on research into thanatologic and posthuman development.

[…]

The study of paracausal science and theory came about from the data available after the space-time trauma now known as the Deimos Event. In that sense, it is largely thanks to MONIST-1 that blink travel, omninet communications, and vastly improved stasis technologies now exist.

Being a sucker for weird sci-fi/sci-fantasy, this sort of stuff is catnip for me. (At times, the game’s descriptions of paracausality and related technologies seems positively Gene Wolfe-esque, another point in its favor.) As you might imagine, the existence of technology and phenomena that circumvents the normal patterns of reality opens up a host of possibilities for gameplay, narrative, and of course, combat.

The Galaxy Awaits…

Everything I’ve described so far barely scratches the surface. For example, I haven’t described the various factions and tribes of non-Union humanity, like the Aun Ecumene, the Karrakin Trade Baronies, and the Voladores, nor have I delved too deeply into the long histories of General Massive Systems, Smith-Shimano Corpro, and the other mech-producing companies. And there’s still so much more of the fall of humanity and the rise of Union that I haven’t covered.

A free version of Lancer’s rulebook is available, though it focuses primarily on gameplay, character creation, and only some of the lore that I’ve described above. Much of this info can also be found on the COMP/CON website. But if you want to truly delve into the game’s lore and setting, then you’ll need to buy the full core book for $25, which also includes info for GMs to create campaigns and encounters.

Even though I have no idea if/when I’ll be able to actually run a Lancer session or campaign — the pandemic makes organizing such events all the more difficult — I’ve still very much enjoyed submerging myself in the game’s rich, imaginative worldbuilding. It’s readily apparent that a lot of thought and creativity has gone into Lancer’s creation, and my own imagination has already benefited from simply thumbing through the pages, looking at the excellent artwork, and pondering the ramifications and storytelling potential of what Miguel Lopez, Tom Parkinson Morgan, and their collaborators have created here.

I love these words that conclude Lancer’s core book:

By conservative estimates, there are 250 billion stars in the Milky Way. A significant majority of those stars are orbited by their own retinues of worlds.

Union space — the entirety of the Galactic Core, the Diaspora, and the Cosmopolita — occupies a fraction of the Milky Way’s Orion Arm. Thousands of worlds. But set against the billions unexplored in our galaxy, Union space is minuscule.

So, what lies beyond?

Go, and tell us what you see.

If that fires up your imagination like it does mine, then Lancer could be your next favorite RPG.