The “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife” and the Challenge of Confirmation Bias

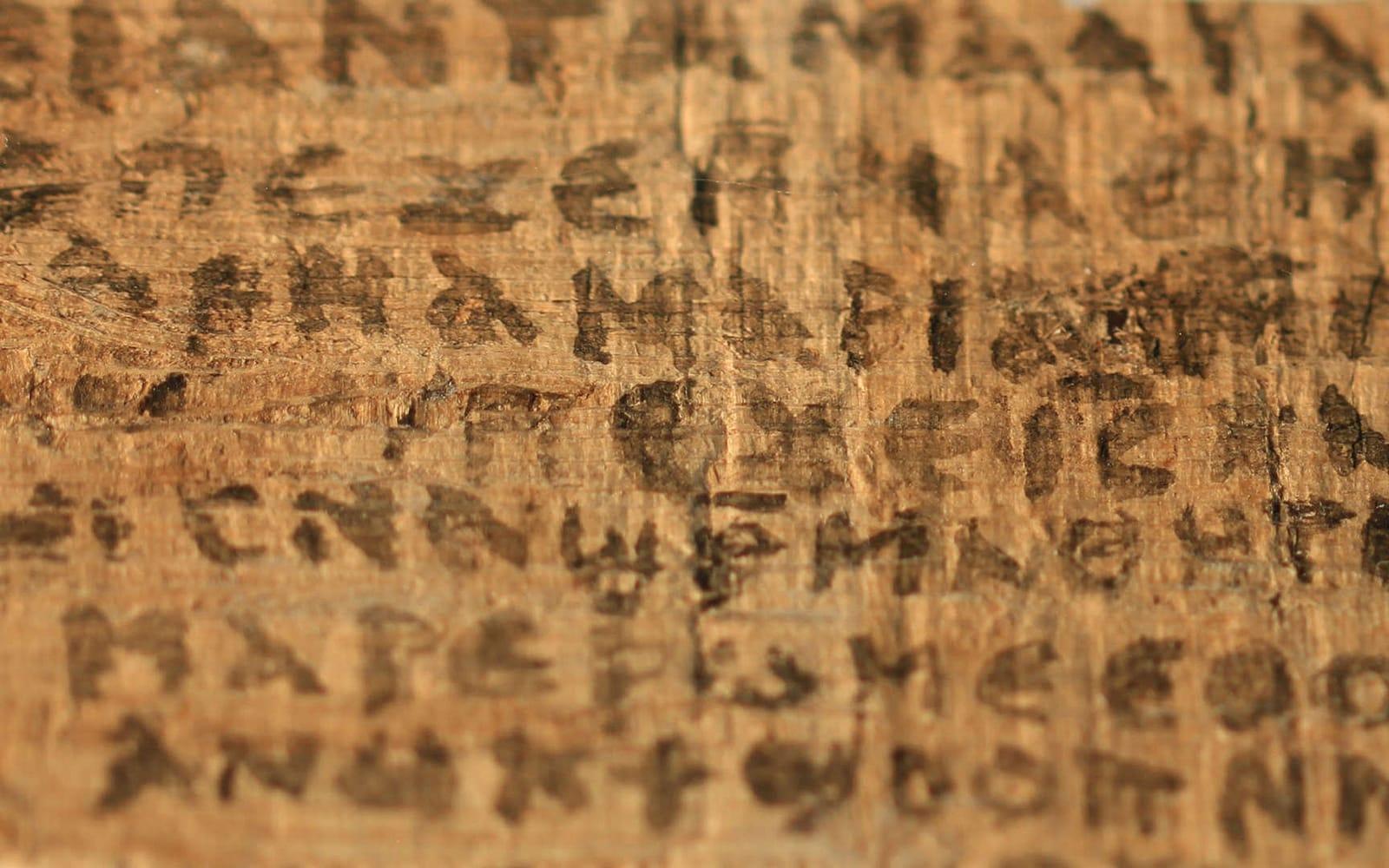

In September 2012, Karen King, a professor of early Christianity and Gnosticism at the Harvard Divinity School, announced that she had discovered a small papyrus fragment in which Jesus referred to his wife. King was careful to explain that the fragment, which she titled the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife,” didn’t prove that the historical Jesus was actually married, but that it did prove that some early Christians believed Jesus was married.

Not surprisingly, King’s announcement was met with considerable attention — and no small amount of controversy. If the fragment turned out to be authentic, it could have repercussions for traditionally Biblical understandings of sex and marriage. But that appears to be an increasingly big “if.” Scholars have begun doubting the fragment’s authenticity, and they’ve noted, among other things, that the fragment was acquired through questionable means and that the owner is hoping to sell their collection to Harvard — both of which cast further doubt on the fragment’s provenance (or history).

Perhaps most damning of all, The Smithsonian Channel has postponed a documentary on the fragment and there are rumors that the Harvard Theological Review may postpone publishing King’s paper on the fragment. (BeliefNet’s Rob Kerby has a written a good overview of the controversy surrounding the “Jesus Wife” fragment.)

If the fragment turns out to be a fake, and it’s increasingly looking like that will be the case, how could this have happened? First Thing’s James Hannam points out that this isn’t the first time that dubious materials have been claimed to shed new insight into the life of Jesus — he references the “Secret Gospel of Mark” and the James Ossuary — and that King’s case offers up another example of the dangers of confirmation bias (i.e., our tendency to prefer information that confirms pre-existing beliefs and ideas). Hannam writes:

As for poor Professor King, it is likely that her publication record of feminist readings of early Christianity made her susceptible to being duped. It is even possible that a hoaxer created the “Jesus had a wife” manuscript with her in mind so that she could act as the “convincer” for a buyer deciding whether to part with hard cash. Professor King made an especially convincing convincer because she was convinced herself. In the case of the James Ossuary, renowned epigrapher André Lemaire authenticated the inscription. He too was convinced. This is an occupational hazard for senior academics (no one cares what junior professors think). In 1983, Hugh Trevor-Roper, ranking historian at Cambridge University, confirmed the authenticity of the “Hitler Diaries” for the London Sunday Times. His reputation never recovered.

I’ve written this before, but it bears repeating: though Christians may scoff at King’s assertions, we can use this as an educational experience. We must employ a healthy skepticism when we come across information that seems too good to be true, when we come across information that confirms our pre-existing narratives a bit too neatly. We’re not nearly as rational and objective as we think we are, especially when we’re all by our lonesome: not only do we need a healthy skepticism, but Christians need each other to challenge our ideas and beliefs.

The Bible says that “a threefold cord is not quickly broken” (Ecclesiastes 4:12). Nor is it quickly duped.

This entry was originally published on Christ and Pop Culture on .