Elsewhere, October 26, 2010

Elsewhere: A collection of interesting links and articles that I’ve come across in the last week or so. Follow me on Twitter for more of the same.

Marlena Graves asks “How should the Church respond to intellectual challenges to Christianity from inside its walls?”

The student captured well the triumphalist, anti-intellectual strain present in some quarters of the church. Of course not all objections to the faith are intellectual in nature. But I can’t help wondering if some of us are unwittingly contributing to the ship-wrecking of faith because we fear to directly and honestly addressing seemingly forceful objections. Do we fear that God and his people cannot handle rational scrutiny? That if we honestly and seriously confront the objections leveled against God and the church, both will be found wanting?

I happen to think the answer is no. In college I majored in history and minored in religion and philosophy. I had my own struggles with doubt. Yet I can’t count the number of times I was given pat answers, presented with straw man arguments, or told, “See, you shouldn’t study philosophy — it only serves to lead you astray.” It is this sort of environment that prompted Christian philosopher Clifford Williams to write, “It is difficult to imagine thinking Christians remaining long in such a condition” (see his The Life of the Mind: A Christian Perspective, 2002).

My husband, a philosopher, and I have become convinced that part of the problem is that we have paid little attention to vices of the intellect: being closed to the ideas of others, an unwillingness to exchange ideas, a poor sense of one’s own fallibility, a disposition to yield to the excitement and rashness of the overly enthusiastic members of a community, an unwillingness to conceive and examine alternatives to popular ideas, a tendency to wilt in the face of opposition, and impatience with thorough, genuine inquiry.

Tim Keller writes about hell, and what it actually tells us about the wrath — and love — of God:

This young man expressed what may be the main objection contemporary secular people make to the Christian message. (A close second, in my experience, is the problem of suffering and evil.) Moderns reject the idea of final judgment and hell.

Thus, it’s tempting to avoid such topics in our preaching. But neglecting the unpleasant doctrines of the historic faith will bring about counter-intuitive consequences. There is an ecological balance to scriptural truth that must not be disturbed.

If an area is rid of its predatory or undesirable animals, the balance of that environment may be so upset that the desirable plants and animals are lost — through overbreeding with a limited food supply. The nasty predator that was eliminated actually kept in balance the number of other animals and plants necessary to that particular ecosystem. In the same way, if we play down “bad” or harsh doctrines within the historic Christian faith, we will find, to our shock, that we have gutted all our pleasant and comfortable beliefs, too.

The loss of the doctrine of hell and judgment and the holiness of God does irreparable damage to our deepest comforts — our understanding of God’s grace and love and of our human dignity and value to him. To preach the good news, we must preach the bad.

Terry Teachout on purging one’s CD collection and the freedom that this brings:

I, too, once felt the mad desire to own every jazz record ever made, and to have them all shelved in chronological order at arm’s length from my desk. Today I own just two racks, and whenever I acquire a new album, I get rid of an old one in order to make room for it. Not only has this imperative made me ruthlessly selective, but it has forced me to reconsider my priorities. Time was when I bought records in order to say that I had them. Now I keep them only because I love them.

[…]

Why have I come to feel this way? Because I’m fifty-four. Life, I now know, is short, too short to waste, and the actuarial tables leave no possible doubt that most of mine has passed me by. As a professional critic, it’s my job — my destiny, you might say — to spend a fair amount of time experiencing art that I don’t like. Insofar as possible, though, I don’t propose to waste any more of the days that remain to me consuming bad art than is absolutely necessary. Unless I’m being paid to do so, I won’t even finish reading a book I don’t like, or listening to a record that fails to engage me. I have better things to do, and not nearly enough time in which to do them.

Via Andy Whitman.

The World’s 8 Nerdiest Religions:

One could almost say that being a Nerd is itself a kind of religion: We have rituals and observances (conventions, TV show marathons, RPGs) prophets (Gene Roddenberry, Isaac Asimov, Stan Lee) holy scriptures (Marvel, DC, Dark Horse), saints (Bruce Campbell, Joss Whedon, Felicia Day), schisms (Star Wars canon vs. EU, Kirk vs. Picard, Transformers G1 vs. Beast Wars), and relics (Action Comics #1, the Boba Fett with the firing rocket pack) — even apostates and devils (George Lucas, Michael Bay)! And most of all, we have the scorn of non-believers who do not share our views and choose to mock what they don’t understand.

Some nerds, however, have taken the next step and formulated their own singular faiths — complete with their own uniquely nerdy deities. The faiths themselves represent a broad range; some are clearly satirical, some are utterly absurd, others are pseudo-serious, and a few even are completely earnest. Thus, we present a look at eight of the nerdiest theologies in existence. Please note that TR neither promotes nor condemns any particular religious creed. If descriptions of individuals and organizations who take a skewed, perhaps irreverent stance on religious faith is offensive to you, you might wish to consider skipping this list.

5 Things You Won’t Believe Aren’t In the Bible:

As a predominantly Christian people, Westerners think they know the Bible pretty well. But not everybody realizes that many of the most iconic features of Christianity were never mentioned by the holy book or the church, but were actually pulled from the ass of some poet or artist years after God turned in his final draft of the Bible.

Robert Lawrence Kuhn asks physicists, philosophers, and cosmologists about the “ultimate” questions:

Theoretical physicist Lawrence Krauss is clear, blunt, and unafraid. “On the whole, I tend to frame these kinds of questions in a scientific vein,” he says. “Obviously, ‘Why am I here?’ comes up often. But the one that more and more drives me is whether the universe has to be the way it is. Is there just one set of physical laws that work? This has long been the guiding principle of science. And we’re coming around to the idea that maybe it’s not true. It would be a profound shift in how scientists think about science.”

How does that make Krauss feel? “It’s depressing,” he says. “Maybe scientists living 100 years from now won’t be so depressed, but sociologically, I grew up wanting to figure out why the universe has to be the way it is, not why it can be some other way.”

He continues: “I’m driven by the possibilities. Not what’s practical — as my wife reminds me — but what’s possible out there. And so I want to know the landscape of possibilities. I’d like to think that I can predict that the universe has to be a certain way. If not, it will certainly be a disappointment to me. But the universe is the way it is whether we like it or not, which is the other important thing that science tells us. I wish more people understood that if that’s the way the universe is, we should live and work with it.”

It may get worse, Krauss laments. “There may be more than just a landscape of possibilities; it could be that the ultimate description of reality is not determinable, even in principle. It’s not that we have a theory that predicts lots of different possible universes and we could be in any of them, but rather that we may not be able to ever show which universes it predicts. It could be mathematically incomplete. It could be that the fundamental theory is not solvable, even in principle, even as a mathematical possibility. This is as bad as it could possibly get — I’ve thought about this in my ultimate stage of depression.”

But Krauss doesn’t give up hope because, he says, “even if we can’t understand ultimate reality, there’s still an incredible amount we can understand about the universe. Suppose we harmonize quantum mechanics and gravity. That isn’t going to have an iota of impact on explaining important things like why consciousness may arise in humans. So even a ‘theory of everything,’ as a friend of mine likes to say, is still a theory of very little.”

A closer look at iPhone transition animations:

iPhone transition animations are cooler than meets the eye.

Take page transitions, for example. It’s common to navigate from one page to another by tapping an item from a list to see more detail: new pages slide in from the right, while tapping Back slides the old page back in from the left.

You might think that animating in a new page to replace the old would simply slide the two in lock-step, like two cafeteria trays on a serving rail, but it’s more subtle than that. To see that subtlety, let’s slow things down for a closer look.

Why the Irish will find it easier to endure the hard times ahead:

…even the newfound excess was frugal by American standards. The Irish use less energy per capita than most Western European nations, and half of the energy per capita as the average American. Personal savings remain much higher in Ireland than in the U.S. Personal debt has increased, but only because so many acquired new mortgages in the last decade.

More significantly, few people here saw the boom as normal or permanent. No leaders announced grandiose plans for a 21st-century Irish Age, or invested their new wealth in forming a global empire. As religious as Ireland has been, no one decided that Ireland was now the chosen nation of God. In short, the Irish did not react as many of my own countrymen did to the rising economic fortunes of the U.S.

Most Americans don’t imagine themselves to have lived through a boom of their own, but they have — just one that has lasted a human lifetime, so few people now remember frugality. The current crisis has left many Americans feeling helpless and outraged: this isn’t supposed to happen to us. The Irish make no assumptions, and now that lean times have returned, any Irish person older than 30 remembers how to live through them.

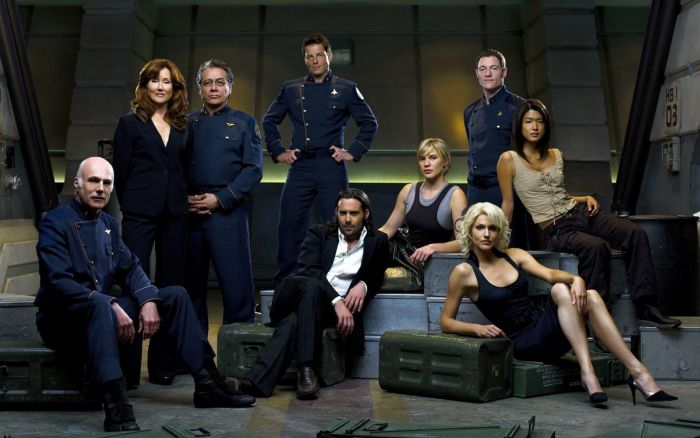

Wired interviews Ronald D. Moore regarding Battlestar Galactica’s lack of technobabble and aliens:

Moore: That’s why I like it. I wanted to make a show that took science fiction back to what it used to really be all about. Science fiction used to be a way to explore society. It was always about today, where the author was at that moment, and took the science fiction prism and altered certain things, [giving] a distance to the audience to examine interesting questions. Questions of morality, existential questions, where are we going as a people, what is technology doing to us, how is the human condition going to change?

I felt that science fiction, especially film science fiction, had gotten away from that. It had become almost solely an escapist medium. And there’s nothing wrong with escapism — I love Star Wars as much as anybody. However, it shouldn’t be the only flavor of this genre. There should be room for the shows that are about examining issues, really challenging the audience, pushing the audience in directions that they may not be comfortable with. I thought, if ever there was a moment to do that, it was at that moment of doing Battlestar Galactica.

Wired.com: We talked a bit about technobabble in the press conference this morning, and drama versus science. Can you speak a bit about that?

Moore: My experience in Star Trek taught me that technobabble could just swamp the drama in a show. Especially in a space opera, where you’re on ships in space and dealing with technical things, technobabble becomes a crutch to get into and out of situations. It just leaches all the drama away. The audience doesn’t know what the hell you’re talking about, and you’re making it up anyway. You make up a problem with the Enterprise warp drive, and then you solve it with a made-up problem, too.

I just did not want Galactica to be about that. I really wanted it to be about the characters and the story. You had to deal with a certain amount of technobabble because of the nature of the world in which they operate, but I really wanted it to be in the background. I really didn’t want the show to be about that, to the point that sometimes I was overcorrecting and just making it simplistic to just get on with it already.

Christopher Yokel learns all about “Haiku Patience”:

…haiku draws much from Zen Buddhism, with its focus upon meditation, enlightenment, and non-intellectual ways of knowing. Haiku may borrow from the Zen idea of satori, “sudden enlightenment, in which in a flash of insight the Zen student suddenly realizes his oneness with the universe” (Cohen). It also seems to borrow the Zen practice of “bringing together seemingly disparate elements by showing their hidden or unsuspected unity.”

I am not Buddhist, but that doesn’t mean I can’t appreciate some of these ideas. As a Westerner, often implicitly driven by the premise of logic and didactic purpose in all things, and as an American driven by our increasingly hurried culture, I can see why I would have a hard time appreciating haiku. The haiku is an invitation to stop and be still, to pay attention to the details happening all around, and to see the beauty in their connectedness. The haiku is not so much a beginning to an intellectual experience as much as it is an invitation to an aesthetic experience, to hear the beauty of the words, and even as haiku poet Gary Hotham says, to hear the spaces in between the words, to sense the vision of the small image being presented.