Elsewhere, November 15, 2010

Elsewhere: A collection of interesting links and articles that I’ve come across in the last week or so. Follow me on Twitter for more of the same.

(Things) Worth Noting reviews a recent Sufjan Stevens show:

To my mind, the concert was an unqualified triumph, an existential meltdown set to synth sounds and spectacle, an acid-laced revival service, a celebratory journey into the complexities and contradictions of the human mind. It was already a gamble to spend the goodwill and critical capital that he’s built up over the past few years on a record like The Age of Adz, and he increased the ante by building his show around an honest, undiluted rendering of that record. We could use more artists with the courage to leave themselves this vulnerable.

The title speaks for itself: “Firefly’s 15 Best Chinese Curses (and How to Say Them)”:

In just 14 episodes, Joss Whedon’s sci-fi masterpiece Firefly managed to build one of the most devoted fanbases in all of nerd-dom. Properties like Star Trek or Doctor Who may have it beat in sheer numbers, but the Browncoats make up for this with their loyalty and tenacity. What is the secret of the show’s appeal? Fans can and will explain the show’s engrossing plotlines, fascinating characters, brilliant performances, realistic effects, and a unique visual aesthetic — but if we had to choose one reason, it’d be the dialogue.

Whedon created a vision of a human future where mankind speaks English primarily, with Mandarin Chinese added, as one might say, for “flavor” (i.e., profanity). Not only did the use of Mandarin help inform Firefly’s future setting, it also often allowed the characters to express themselves in terms too absurd, obscene, or outrageous to be spoken in English. Here then is a collection of 15 of Firefly’s most, well — absurd, obscene, and outrageous lines ever delivered in Mandarin Chinese.

My favorite? It’s a tie between “Holy Mother of God and All Her Wacky Nephews” and “Holy Testicle Tuesday”.

Roger Scruton: “Effing the Ineffable”:

There is nothing wrong with referring at this point to the ineffable. The mistake is to describe it. Jankélévitch is right about music. He is right that something can be meaningful, even though its meaning eludes all attempts to put it into words. Fauré’s F sharp Ballade is an example: so is the smile on the face of the Mona Lisa; so is the evening sunlight on the hill behind my house. Wordsworth would describe such experiences as “intimations,” which is fair enough, provided you don’t add (as he did) further and better particulars. Anybody who goes through life with open mind and open heart will encounter these moments of revelation, moments that are saturated with meaning, but whose meaning cannot be put into words. These moments are precious to us. When they occur it is as though, on the winding ill-lit stairway of our life, we suddenly come across a window, through which we catch sight of another and brighter world — a world to which we belong but which we cannot enter.

[…]

But a question troubles me as I am sure it troubles you. What do our moments of revelation have to do with the ultimate questions? When science comes to a halt, at those principles and conditions from which explanation begins, does the view from that window supply what science lacks? Do our moments of revelation point to the cause of the world?

Brett McCracken takes comfort in rituals:

…there’s something transcendent about repetition, about the mundane and predictable patterns of life. The seasons, for example. They happen every year, like clockwork… and there’s something gloriously moving about that.

Paradoxically, it seems that things like repetition, ritual, and regularity actually make our battle against time easier. The tyranny of time – which is that it constantly reminds us of impermanence, deterioration, and mortality – is somehow diminished in rituals, which help bring a semblance of continuity and constancy to an otherwise constantly changing existence.

If birth rates are any indication, it will be the ultra-religious, not the secularists, who inherit the Earth:

…today’s strongly religious people tend to have a relatively large number of children, whereas secularists increasingly have few, if they have them at all. If you believe in evolution (and what secularist doesn’t?), then you have to take this thoroughly naturalistic explanation for God’s comeback into account.

To be sure, in countries rich and poor, under all forms of government, birth rates are declining across the globe. But they are declining least among those adhering to strict religious codes and literal belief in the Bible, the Torah, or the Koran. Indeed, the pattern of human fertility now fits this pattern: the least likely to procreate are those who profess no believe in God; those who describe themselves as agnostic or simply spiritual are only somewhat slightly less likely to be childless. Moving up the spectrum, family size increases among practicing Unitarians, Reform Jews, mainline Protestants and “cafeteria” Catholics, but the birthrates found in these populations are still far below replacement levels. Only as we approach the realm of religious belief and practice marked by an intensity we might call, for lack of a better word, “fundamentalism,” do we find pockets of high fertility and consequent rapid population growth.

[…]

Ironically, the structure and sensibility of secular society is bringing about its own demise. By the 1960s, expanding secularism may have set back religion severely as a force in history, but in doing do so, it strengthened the remaining strongholds of faith and set in motion patterns of reproduction and acculturation that would allow its most fundamentalist forms to reclaim the future. Though there may of course be a deeper reason, one need believe no more than this to understand why the God who was missing in my childhood has returned.

How can graphic designers and illustrators capture the look of H.P. Lovecraft?

Lovecraft has always posed a problem for anyone trying to turn the writer’s nightmares into visual imagery. The stories’ peculiar pleasure lies in the fully developed mythology that interconnects them, and in the morbidly refined vocabulary Lovecraft uses to evoke cosmic horrors too awful to describe, monstrous things from out of space and time too unfathomable to name, treading a fine line between an exquisitely apt descriptive style and embarrassingly purple prose. Lovecraft’s warped psychology and aberrant obsessions are best savored within the limitlessly accommodating theater of your own imagination. The risk with any attempt to make his spectral inventions literal and solid is that they will just look silly.

Via @jasonsantamaria

Philip Yancey discusses Christianity’s role and existence in the Middle East:

Much of the misgiving that Muslims feel for the West stems from our strong emphasis on freedom, always a risky enterprise. I’ve heard some say they would rather rear their children in a closely guarded Islamic society than in the United States, where freedom so often leads to decadence. An Egyptian Christian told me he cannot check into a hotel room with a woman until they show evidence that she is his wife — a policy he appreciates, as does his wife. We could also learn from the Islamic emphasis on family. Middle Eastern émigrés to the West are shocked to find us shuttling preschoolers off to daycare and elderly parents to nursing homes.

Although there may be advantages to living in the Middle East, Christians here face the daily challenge of practicing their faith as a small minority in a culture that may sometimes seem hostile. How can they stay true to their beliefs and present a different picture of Christianity to their Muslim neighbors? Fortunately, they have a good model to follow: the original Christians who came from this region.

Yet another example of why I like and appreciate Yancey’s writings so much. The article is a condensed excerpt from his latest book, What Good Is God?: In Search of a Faith That Matters, which I still need to purchase.

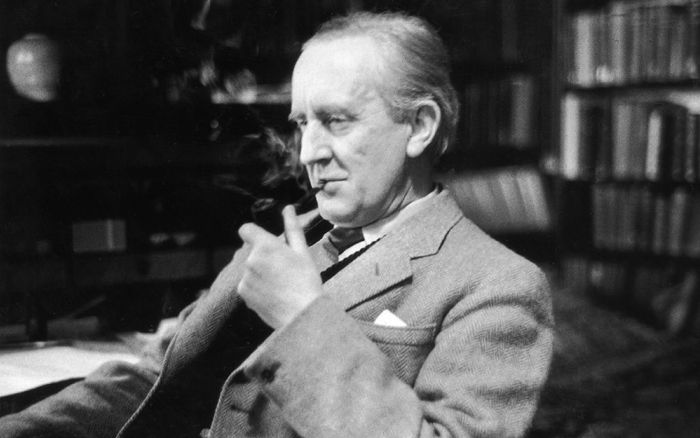

J.R.R. Tolkien and Anarcho-Monarchism:

One can at least sympathize, then, with Tolkien’s view of monarchy. There is, after all, something degrading about deferring to a politician, or going through the silly charade of pretending that “public service” is a particularly honorable occupation, or being forced to choose which band of brigands, mediocrities, wealthy lawyers, and (God spare us) idealists will control our destinies for the next few years.

But a king — a king without any real power, that is — is such an ennoblingly arbitrary, such a tender and organically human institution. It is easy to give our loyalty to someone whose only claim on it is an accident of heredity, because then it is a free gesture of spontaneous affection that requires no element of self-deception, and that does not involve the humiliation of having to ask to be ruled.

How Hollywood killed the movie stunt:

The decline of classical filmmaking, coupled with cinema’s increased reliance on computer-generated or computer-burnished imagery, has pretty much destroyed the specialness — the magic — of movie stunts. You can’t appreciate what you can’t see. And it’s harder to appreciate the unusual nature of a physical achievement when the entire movie strives to make every moment seem thrilling, astonishing and intense — a phenomenon I wrote about in a 2009 Salon piece about the director Michael Bay, who seems to believe there is no such thing as a small moment, and whose hyperactive action pictures suggest what Nike ads would look like if they were directed by killer cyborgs on cocaine.

[…]

I wonder if we’ll see a resurgence of low-tech, stunt-driven action as an antidote to high-tech sorcery. I hope so; with the right context and the right attitude, a wide shot of a man jumping out of a burning balloon could be more exciting than 300 computer-generated avatars charging across a battlefield made of ones and zeros while the director runs and guns and cuts, cuts, cuts.

I hope so, too. I like CG-enhanced special effects as much as the next guy but nothing beats a classic Jackie Chan film for excitement and thrills. Via @ebertchicago

Do secularists feel cheated when discussing God with believers?

[The secularist] argues that people take to religion as a crutch, because they can’t get through life without help — or, as he thinks, the illusion of help — and the Christian and Jew and Muslim smile benignly and admit they can’t. They explain that we are crippled by sin and death, and God has graciously provided the aid we need. The lifesaving ring someone throws you when you are drowning remains real even though you want it desperately.

He may also argue that we believe in God because we have a “God gene” and are hard-wired to do so, and again the religious believer smiles benignly and admits that we might well have a God gene. He suggests that a loving creator might well arrange our wiring to make belief easier, knowing how hard it will be for us.

Or the secularist may argue that we believe in God because we want to claim Divine sanction for our worldly interests and desires, and points to the allied and German soldiers in World War I singing hymns as they tried to kill each other, and the religious believer shakes his head sadly and admits that many Christians have done this from the beginning. He shrugs and explains that God loves his creatures even though they make a mess of his gifts, and that some of them get it right anyway.

No evidence of the human origins of religious belief will upset the religious believer, because he can always appeal to a very convenient, and convently mysterious, relation between God and a defective humanity. It’s all grace, he will say. What seems like good evidence that religion is a sham looks to the believer like yet more evidence that God loves us.

An interesting interview with physicist and priest John Polkinghorne:

Q: What do you say to people of faith who, despite what science says about how old the Earth is, say, “I don’t care what science says — – I just believe in the Bible?”

A: I would say that I believe in the Bible, too. But what I try to do is try to treat the Bible respectfully and in the right way. The Bible is not a book — – it’s a library, and it has lots of different sorts of writing in it. You have to figure out what you’re reading. If you read poetry and think it’s prose, you’ll make some very bad mistakes. The poem that says “My love is like a red, red rose,” doesn’t mean the writer’s girlfriend has green leaves and prickles. You know it’s poetry and not prose. When I read Genesis 1 and 2, I am not reading a divinely dictated textbook of science, telling me how things happened in the early universe. It’s saying something deeper than that. I’m reading a theological piece of writing, where God said “Let there be,” and things came to be. The irony is that the people who read the Bible in a sort of crass, literalist way, as if Genesis 1 is describing six hectic days of divine activity, are actually abusing the Bible rather than honoring it. Which is sad, really.

Q: A lot of people in science think the Bible is one big fairy tale. You’re a pretty smart guy. Do you believe in fairy tales?

A: (laughs) I certainly don’t believe in fairy tales. People who say that about the Bible are making a big mistake. They’re not recognizing the genre — – the kind of writing — – that makes up the Bible. Of course there are stories in the Bible, but there is also an enormous amount of history in the Bible. The Gospels tell of a very remarkable man and a very remarkable life and an extraordinary death that seems to have ended in some sort of failure and desertion, where Jesus says “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” Nevertheless, the story continues. I think something happened to continue that story.