Disney’s Black Hole: A Flawed, Fascinating Sci-Fi Epic

Considering the number of people who worked on its script and storyline (seven, by my count) and the number of years it spent in development hell, it’s kind of amazing that Disney’s The Black Hole ever got made in the first place. Originally envisioned as a disaster film à la The Poseidon Adventure set in space, The Black Hole passed from production crew to production crew, which explains its schizophrenic nature.

Part space gothic horror (complete with a mad scientist), part clownish robot antics, part space exploration epic, The Black Hole — which was finally released in 1979 — is a fascinating mess of a movie that’s well worth watching in spite of its flaws.

Seeing as how this movie is over forty years old, I’m not too concerned if anything gets spoiled. But even so, the following contains potential spoilers for The Black Hole.

Set at some point in the future, The Black Hole begins with the crew of the USS Palomino returning to Earth after a deep space exploration mission. Their journey is interrupted by the discovery of a massive black hole, and even more fascinating, a giant spaceship — the USS Cygnus, which had previously been assumed lost — floating nearby in defiance of the black hole’s gravitational pull. After barely surviving their own encounter with the black hole’s gravity, the Palomino crew dock with the Cygnus for repairs.

Thought it seems abandoned at first, the Cygnus is crewed by faceless, black-robed androids and their commander, Dr. Hans Reinhardt (Maximilian Schell), a brilliant, if somewhat unorthodox, scientist. Reinhardt claims that the Cygnus’ human crew abandoned ship decades earlier, but the longer the Palomino crew stays on the Cygnus, the more they suspect that Reinhardt’s not telling the whole truth. And when he announces his plans to travel through the black hole, they realize they need to get off the Cygnus as soon as possible. However, Reinhardt — who, by this point, is clearly less than sane — might have other plans for our stalwart heroes.

The Black Hole really works best in its first couple of acts, as the Palomino discover and explore the Cygnus while slowly growing suspicious of Reinhardt’s story. The Cygnus itself helps set this mood, thanks to its foreboding external design and vast, empty interiors. The movie’s production design crew clearly earned their paychecks on this one. The Cygnus is by turns ominous, lavish, overwhelming, and haunting — be it the Eiffel Tower-looking exterior, the towering walls of computer screens and displays on the ship’s bridge, Reinhardt’s luxurious quarters, or the empty, brutalist-looking quarters of the absent human crew.

The faceless android crew also adds to the movie’s ominous atmosphere as the Palomino crew catch glimpses of their strangely human behavior. In the movie’s best scene, the Palomino captain (Robert Forster) comes across some of the Cygnus crew holding a funeral that’s surprisingly reverent, and all the more eerie because of it. And then there’s Reinhardt’s robotic first mate, the malevolent Maximilian, who looks positively demonic with his red armor, glowing red visor, and various clawed appendages. (Which becomes rather fitting in the movie’s final sequence.)

Unfortunately, much of the movie’s remaining runtime suffers from some strange tonal shifts, due in large part to the aforementioned robot antics. One of the Palomino’s crew members is a floating robot named V.I.N.CENT (voiced by Roddy McDowall), who often communicates in humorous proverbs, and who discovers his counterpart on the Cygnus, a broken down robot named Old B.O.B. (voiced by Slim Pickens). Together, the two of them investigate Reinhardt’s plans while running afoul of his security robots (including a rather silly, Old West-style shootout complete with twirling guns).

This particular moment, as well as the climactic battle — during which V.I.N.CENT and Old B.O.B. fly through the air with the greatest of ease while blasting security robots — clearly feel like attempts to clone Star Wars’ blend of action and humor. (Star Wars was released two years earlier.) But compared to the earlier acts, when the Palomino crew meet Reinhardt and begin making sense of the Cygnus’ existence on the edge of the black hole, these robot-centric scenes feel like they belong in an entirely different movie, and only exist in The Black Hole to make it more kid-friendly (and sell some toys).

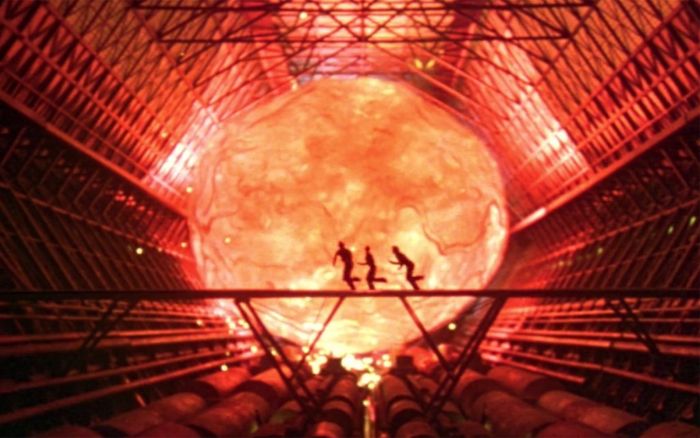

However, by the time the movie enters its final act, the weirdness reasserts itself — and then some. As Reinhardt begins his plunge into the black hole, the Palomino crew are betrayed by one of their own and must find another way off the Cygnus, which becomes increasingly damaged by asteroids. (This sets up one of the movie’s most iconic and visually arresting scenes, with the remaining Palomino crew members racing through the Cygnus while its innards are torn up by a massive asteroid.)

The Palomino crew finally make it to an escape craft, only to discover to their horror that its controls are also set for the black hole — and so begins what is arguably one of the strangest scenes of any Disney movie. I’d try describing it, but you probably wouldn’t believe me, so just watch it for yourself.

Yes, that’s right. You actually did just see that. Reinhardt and Maximillian become fused together and trapped in hell, which is also populated by the Cygnus’ faceless android crew. (Which, we learned earlier in the movie, were actually the Cygnus’ human crew who attempted to mutiny against Reinhardt, only to be lobotomized and enslaved.)

As for the remaining Palomino crew, they’re guided by an angelic being through what looks like a glass cathedral and emerge out the other side of the black hole. As an added bonus, it’s all soundtracked by a gorgeous score courtesy of John Barry, who’s best known for his work on the James Bond franchise (and there’s definitely some 007-esque bombast in the above scene).

Although the movie ends with the Palomino crew heading towards another planet, the story was picked up in a series of comics published in 1980. There, the Palomino crew pass into a parallel universe where they see their doppelgangers and encounter a different Dr. Reinhardt who is more interested in planetary conquest than space exploration. They also encounter the Virlights, one of the few alien races to stand up to Reinhardt. Oh, and they fight a dinosaur, because why not?

The comic series ended after four issues (a fifth issue was planned but never printed), and I’m not certain how canonical they’re considered to be, so the fate of the Palomino crew was left open-ended. However, there have been attempts to remake The Black Hole anew. Director Joseph Kosinski (Oblivion, Tron: Legacy) was attached to the project as far back as November 2009. Production stopped in 2016 because the script was considered too dark but has since restarted with Emily Carmichael (Jurassic World 3, Pacific Rim: Uprising) writing a new script. Apparently, the new Black Hole movie — if it ever happens — is destined to go through a development hell similar to that of its predecessor.

Personally, I’m somewhat ambivalent concerning a remake. While I’d love to see what modern effects could do for the Cygnus and the black hole itself, I worry that Disney would play it too safe. I actually like the darkness and madness of the original movie, most notably in the form of the brilliant-but-insane Dr. Reinhardt. Furthermore, the eeriness of the Cygnus and its crew feels quite appropriate considering their proximity to a black hole, a place where the laws governing reality are broken down and reduced to almost nothing.

For all its flaws — like V.I.N.CENT and Old B.O.B.‘s various hijinks — The Black Hole is a throwback to when Disney was perhaps a little more adventurous and willing to put out strange stuff. Other Disney films released around this time included The Cat from Outer Space, Escape to Witch Mountain, Dragonslayer, Condorman, Unidentified Flying Oddball, The Watcher in the Woods, and Gus (a film about a football-playing mule). I’m not saying these were all good films (though I have a certain fondness for The Cat from Outer Space and Condorman), but they weren’t uninteresting, and they represent a greater diversity of ideas than what you might see from Disney these days.