Tony Takitani by Jun Ichikawa (Review)

After hearing so much about his writing, I finally got around to reading Haruki Murakami for myself, beginning with The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, and I wasn’t disappointed. Murakami’s writing style is lethargic and surreal, full of intriguing characters whose obtuseness and alienation make them all the more compelling. I found myself completely captivated. And as these things go, I naturally found myself wondering what a movie based on Murakami’s work might look like.

So when I found out about Tony Takitani, it immediately jumped to the top of my list, and doubly so when I found out that it would be coming out on DVD here in the States in early 2006. And the movie did not let me down one bit, living up to all of my expectations, and then some.

Based on a Murakami short novel — the man is apparently very guarded about his other, more famous works being translated into film — Tony Takitani tells the story of a man named, well, Tony Takitani (Yi Yi’s Issei Ogata). The thing about Tony is that he is lonely, very lonely.

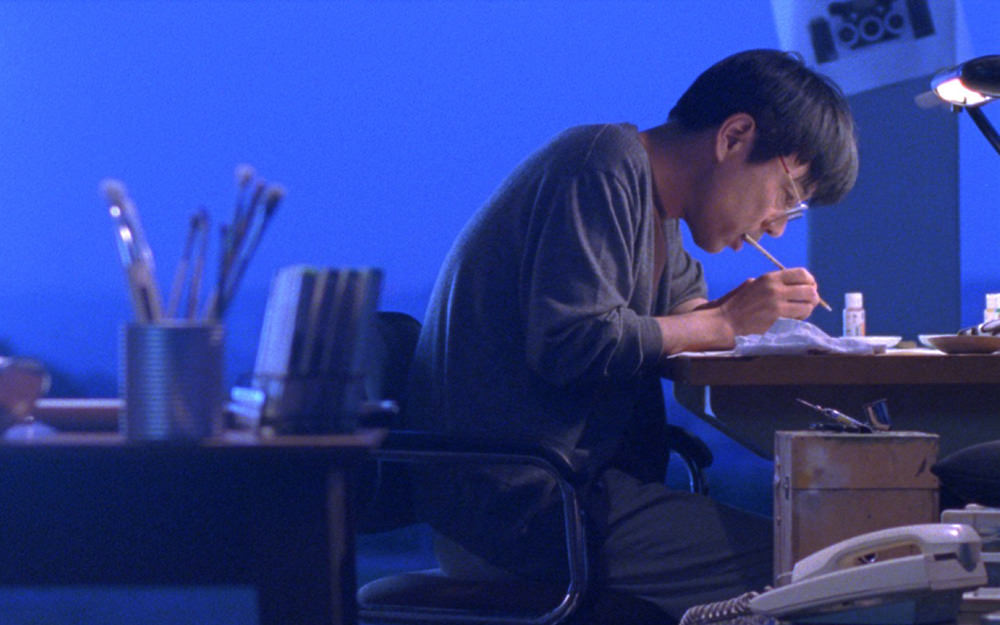

His mother died shortly after he was born, his jazz musician father only drops by every couple of years, and while Tony’s fastidious attention to detail may serve him well as an illustrator, it doesn’t really help him when it comes to human relationships. The result is a man who is so alone, he doesn’t even know he’s alone — he knows nothing else but solitude.

Until, that is, a woman comes into his life. Eiko (The Twilight Samurai’s Rie Miyazama) is like a breath of fresh air, instantly catching Tony’s attention when she shows up at his office to pick up some work. Tony finds himself completely smitten with her, and though he’s quite a bit older than she is, the two of them eventually marry.

It’s a lovely marriage, and all seems well, except for one slight thing. Eiko is obsessed with buying new clothes. Just walking past a department store is enough to send her into a binge. As much as Tony loves his wife, her addiction is cause for concern. However, when Tony finally mentions something, and asks her to practice a little moderation, he sets in a motion a series of tragic events.

To say anymore would mean robbing any potential viewers of a powerful experience. Not having read Murakami’s original story, I can’t say how faithful writer/director Jun Ichikawa is to the source. But what I can say is that Tony Takitani the movie is one of the more poignant and affecting films I’ve seen in a long time, a very powerful movie about longing and loss.

I suppose that, subconsciously, I was expecting something along the lines of Wong Kar-Wai movie, since Wong has practically made a career of making movies whose central themes are unrequited love, loneliness, and alienation. While Tony Takitani does share some similarities to Wong’s films — i.e. voiceovers and exquisite visuals — Tony Takitani is much more skeletal and direct, with none of the drawn out melodrama that one might find in a Wong Kar-Wai piece.

Given the film’s 75 minute runtime, Ichikawa doesn’t have a lot of time to waste, and so he doesn’t. Every shot, movement, camera motion, and bit of dialogue feels composed and pared down, carefully honed to deliver as much emotional impact as possible. The result is a film that is very economical and frugal. Nothing is wasted; even the sets are stripped down to the barest essentials, and filmed so that everything inessential is cropped out.

And then there’s Ryuichi Sakamoto’s sparse soundtrack. Though perhaps a bit to repetitive and saccharine at times, Sakamoto’s piano pieces are absolutely perfect for the mood of the film, casting a contemplative and melancholy spell over the visuals. One moment in the film that sticks out especially in my mind is when Eiko first appears. As she walks up the stairs to Tony’s office in slow motion, Sakamoto’s score suddenly shifts a bit. New notes come skipping through and the pace seems to quicken, lightening the mood and perfectly capturing the brightness that Eiko brings into Tony’s life. And yet the music remains fragile, reminding the viewer that this Eiko’s joy is perhaps transient at best.

Although there are plenty of arthouse-isms to Tony Takitani — the sparse dialog and ultra-minimal acting, the stripped down approach, etc. — it is nonetheless a very affecting film, and never feels artificial or forced. Ogata does a fantastic job here, conveying Takitani’s loneliness and the toll that it taken on him without him even noticing with the smallest details — his posture, his eyes, the way he subtly changes in Eiko’s presence. And it’s obvious why he would fall for Miyazama’s Eiko.

Miyazawa presents Eiko, not as a selfish, shallow fashion-obsessed female, but as a woman whose desire for and appreciation of beauty is so great, it might be her undoing. Despite her clothing fixation, she truly does love Tony, and their relationship, though a bit on the sparse side due to the film’s rigorous nature, is still nonetheless convincing and heartfelt.

Which explains why the film’s final act is so wrenching. I won’t spoil what happens, but suffice to say that as a fairly new husband, there are some scenes in the film’s final act that left me haunted. They’re handled in the exact same manner as the rest of the film — with great subtlety and economy, with all of the dross stripped away, making the loneliness and alienation at the core of Tony’s existence keenly felt with only the simplest and most graceful of gestures.