The Twilight Samurai by Yôji Yamada (Review)

When the 2004 Academy Award nominations were announced, I was absolutely thrilled to see The Twilight Samurai listed as Japan’s entry for “Best Foreign Picture.” I had just seen the movie several weeks earlier, having finally bought the DVD after reading so much about it for the past year or so and how it was cleaning up at festivals around the world. Having now seen the movie 3 times (and I’ll probably be going on viewing #4 here shortly), I personally consider it an instant classic, and I find it easy to foresee it joining the ranks of such genre classics as Yojimbo, Harakiri, and Zatoichi.

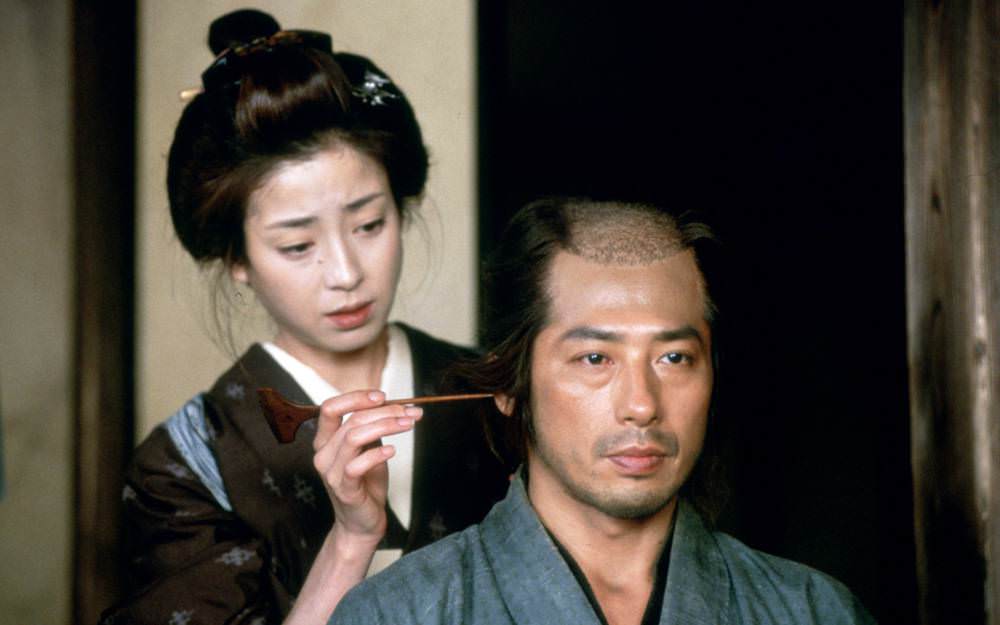

Although I found it a completely involving and affecting film, it’s safe to say that The Twilight Samurai is probably not what most people would expect from a samurai movie. The Twilight Samurai tells the story of Seibei Iguchi (Hiroyuki Sanada), a low-ranking samurai of the Unasaka Clan. From the first time he appears, it’s obvious he’s not your typical silver screen samurai.

He doesn’t appear to be a skilled warrior. In fact, he works as a bookkeeper in the clan’s storehouses, cataloging food supplies. Nor does he carry himself with any sort of swagger or pride, a la Toshiro Mifune. Rather, he just sort of shuffles about in his torn clothing, unkempt hair, and downcast expression. All in all, he seems more inclined to be a farmer instead of a proud and deadly warrior. And truth be told, that’s how Seibei would prefer to live. He’s perfectly content living a humble life far removed from the sweeping changes that are about to engulf his clan and country.

However, his life is not without hardship. He’s a recent widower, his wife having died from tuberculosis. Her funeral has left him deep in debt and he must now care for his two young daughters, Kayano and Ito, and his senile mother all by himself. A famine is currently sweeping through the country and to support his family, Seibei takes odd jobs in addition to his other duties. As a result, he has no time to associate with his fellow samurai, who mock him and nickname him “Twilight Seibei.”

Having no time to look after himself, his appearance becomes rather bedraggled, and after an embarrassing incident with the clan leader, he becomes the laughingstock of the clan and a disgrace to his family. Still, Seibei’s perfectly content to look after his beloved daughters, refusing to remarry for fear of how the change will affect them. But change is coming, and several events threaten to disrupt Seibei’s simple life.

The first is the return of Tomoe (Rie Miyazawa), his friend Tomonojo’s sister and Seibei’s childhood sweetheart. Tomoe had been married to Toyotaro, a rich and powerful samurai, but left him after she couldn’t stand his drunken abuse any longer. While living with her brother, she soon becomes a regular visitor at Seibei’s household, helping with the chores and bringing a much-needed woman’s touch with her.

Kayano and Ito adore Tomoe, and her presence rekindles old feelings in Seibei’s heart as well. Tomonojo urges Seibei to marry Tomoe, knowing he’ll be a good husband unlike Toyotaro, but Seibei is torn. While he loves Tomoe and knows she’ll be a wonderful mother, he’s ashamed of his lowly status, afraid that Tomoe, who comes from a wealthier family, will come to hate being married to a samurai as poor as he.

However, even as Seibei’s personal life is going through turmoil, his clan is about to explode as well. The leader has died and a power struggle is ensuing, with various factions vying for control. The clan attempts to consolidate its power and begins ordering the rebels to surrender and/or commit hara-kiri. One rebel, Zenemon Yogo, refuses to obey, believing that he’s done nothing wrong and that the clan has betrayed him. The clan attempts to force Yogo, but being one of the clan’s finest swordsmen, he’s able to defend himself and holes up in his house.

Although he doesn’t look it, Seibei is a master swordsman himself, as we learn when he confronts Tomoe’s ex-husband and defeats him with nothing but a wooden stick. He’s especially skilled with the short sword, which the clan figures will be advantageous for fighting in the close quarters of Yogo’s house. The clan orders Seibei to bring back Yogo’s head within a day, but Seibei is reluctant. He doesn’t want to leave his family, nor is he entirely confident in his abilities, having been unable to develop them while tending to his family. However, he can’t refuse a direct order from the clan and sorrowfully accepts.

Seibei arrives at Yogo’s house and finds the man drunk and reflective. Yogo tells of his life, one fraught with hardship not unlike Seibei’s. Yogo is a widower as well, and has also lost his teenage daughter, and now he must kill himself because the his superior just happened to be on the wrong side of the clan’s recent upheaval. Although Seibei is sympathetic to the man’s plight, the duel is inevitable, and the two soon launch into a bitter and fierce battle that finds Seibei at a clear disadvantage.

I’m not sure if this counts as a spoiler or not, but the movie does have a happy ending, albeit one that is ultimately bittersweet. The movie’s final scenes are a fitting end, as we watch the now-grown Ito (who serves as the film’s narrator) memorialize her father. Samurai films are always resplendent with themes of loyalty and honor (indeed, that’s one of the reasons why I love them so), and The Twilight Samurai is no different. But The Twilight Samurai looks at honor and loyalty of a different sort, and from a different perspective.

Throughout the movie, Seibei rejects the honor and glory that those around him seek, as his attempt to refuse the clan’s order shows. Yet there is no doubt that he’s an honorable man, as his devotion to his family, and to Tomoe proves. It’s a smaller, perhaps less awe-inspiring honor that doesn’t involve valiant deeds and courageous battles, and yet it’s worthy of great stories nonetheless. While watching Seibei’s devotion, I found myself thinking of my father. Like Seibei, he has never sought out fame or greatness, and yet I can think of no better example of honor or integrity that I can pattern myself after.

Samurai films are also full of memorable performances, from Toshiro Mifune’s Yojimbo and Tatsuya Nakadai’s Hanshiro to Tomisaburo Wakayama’s Ogami Itto and Shintaro Katsu’s Zatoichi. Add to that list Sanada, who delivers an absolutely wonderful performance as Seibei, the samurai who is much, much more than he appears to be. Sanada (who some might recognize from his role as Ujio in The Last Samurai, or as Onmyoji’s villainous Doson) takes Seibei as written in the script and fully fleshes him out, delivering a nuanced performance as a deep and conflicted character. There’s an aura about his performance, such that even when his face is expressionless, the way he carries himself, even the way he shrugs emotes volumes.

I suppose some of the things he does might strike one as perhaps a bit too PC or modern. For example, he encourages his daughters to learn in an era when sewing was considering the only proper education for girls. And he refuses to remarry simply to get a wife partially because he considers it dishonorable to the woman in question. Still, these are not quibbles by any means, and something about them allows Seibei to ring as far truer and more human than many other well-known samurai characters that often come across as (very cool-looking) cardboard cutouts who simply glower, swagger, and wield a big katana.

Of course, Sanada, who was a member of Sonny Chiba’s Japan Action Club and got his start as an action star, delivers solidly in the film’s two action scenes. After all, no samurai movie would be complete without at least some swords being drawn. However, there is nothing flashy or showy about The Twilight Samurai’s two fights (the first being Seibei’s duel with Toyotaro, the second his housebound duel with Yogo). They are physical and rough as opposed to stylized, and in the case of the latter, surprisingly brutal.

Special mention should also be made of Rie Miyazawa, who imbues Tomoe with a palpable sense of longing and sadness. At first, it starts off somewhat cutely as Tomoe tells embarrassing stories to Seibei’s daughters, but it slowly matures over the film’s course. In one of the film’s most powerful scenes, Seibei asks her to help him prepare for his duel with Yogo. As she helps, few words are said… but none need to be. While waiting for the soldiers to come and take him away, Seibei finally confesses his love to her, asking her to marry him should he return — only to discover that she has already become engaged to another. After he leaves, Tomoe moves through the house, gently caressing Seibei’s items before giving a heart-wrenching confession to Seibei’s senile old mother.

Most samurai movies are considered epics, and rightfully so. Films like Ran and The Seven Samurai are as epic as they come. The Twilight Samurai works so well because it is not an epic. As I was watching The Twilight Samurai, I couldn’t help but compare it to The Last Samurai. Just for the record, I enjoyed The Last Samurai (its troubled retelling of Japanese history notwithstanding) and loved its technical aspects (cinematography, music, costumes, sets, etc.). But it came nowhere near as close to drawing me into its world as The Twilight Samurai did. While it’s obvious which of the two movies had the larger budget, it’s also obvious which of the two movies feels more natural, more realistic, and more enveloping.

While the film’s acting has much to do with this, much of the credit also lies with director Yoji Yamada. Yamada wisely sticks with the tiny details and little aspects. But rather than try to delve into their Zen meanings, as The Last Samurai did, and bogging the film down with melodrama and over-philosophizing, he presents them in an almost quasi-documentary fashion, adding to the film’s credibility while also helping to build up and deepen his characters, namely Seibei (you feel much more drawn to the man when you see the humility of his existence and the manner in which he carries himself in spite of it). And while the center of the film is warm and emotional, Yamada surrounds it with grim details — Seibei’s disgrace, the clan’s unrest, the effects of the famine (the corpses of those who died of starvation are often seen floating down the river), etc.

Again, all of the above is just yet one more example of a small, intimate, and unassuming movie saying and emoting things that bigger epic-style films just aren’t capable of, or bog down with unnecessary excess. And as a result of its small, intimate, and unassuming approach, The Twilight Samurai is simply a masterpiece, rightfully deserving of its Academy Award nomination, as well as all of the acclaim it’s received so far. But more importantly, it deserves a well-earned place in the pantheon of great samurai films, a modern classic that easily holds up next to the great films of yesteryear.