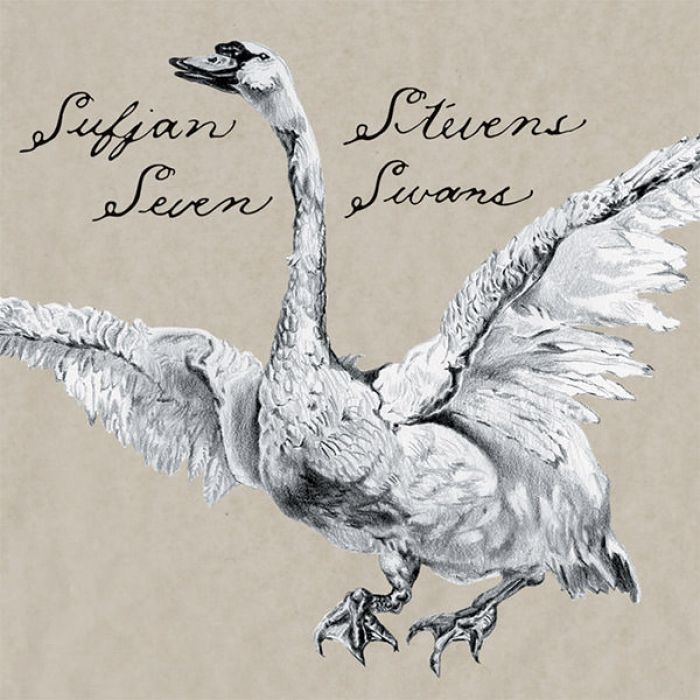

Seven Swans by Sufjan Stevens (Review)

I don’t think it’s even been a year since Sufjan Stevens’ Michigan arrived in my mailbox (and shortly thereafter became one of my fave albums of 2003), but we’ve already got a brand new album of original material from the man to savor. And this won’t be the only Sufjan release we see in 2004, either. Asthmatic Kitty is re-releasing Michigan as a limited edition double vinyl which will include the outtakes that, until recently, were available on his website. And rumor has it that a Christmas recording will also be released sometime this year, drawing from a series of EPs that have only been available at concerts.

One has to wonder if releasing such a large amount of material in such a relatively short amount of time is the wisest of moves. After all, you don’t want to risk saturating the market or draining the creative juices. But luckily for us, Stevens hasn’t been paying attention to the conventional industry wisdom. There’s always room in “the market” for music this inspired, and it’s obvious throughout Seven Swans that Stevens is nowhere close to scraping the bottom of the barrel when it comes to inspiration and creativity.

Seven Swans is more stripped down and naked than anything Stevens has released to date. Gone are many of the embellishments and textures that made Michigan and Enjoy Your Rabbit such fascinating listens, and those that do remain have a much more skeletal form. But rather than feel constrained or limited, the album feels much more liberated as a result, as if unencumbered by past arrangements and experimentation. And being stripped of those things reveals his songwriting for the beautiful creature that it is.

The deftly-picked guitar of “The Dress Looks Nice On You” moves with a fluid grace unlike anything else in Stevens’ repertoire, and is followed by banjo flurries and Stevens’ hushed voice, which has never sounded this pensive. “Abraham” is easily the most delicate song Stevens has yet recorded, a wisp of fragile guitar and barely-there vocals that sounds like it could dissolve in the slightest of breezes. And “He Woke Me Up Again,” its autumnal tone heightened by a shivering organ and graceful guitar and banjo weaves, sounds like it was written for the end credits of a Wes Anderson film.

But the real strength and beauty of Seven Swans, as was the case with Michigan, lies in Stevens’ lyrics. However, Seven Swans differs from Michigan on two counts. First of all, it’s not a conceptual album per se (and in case you were wondering, it’s not the next in his “50 States” series). Second, and most important of all, this is the most spiritual album Stevens has released yet. While his previous records have never been devoid of this aspect, it’s never been as upfront and revealed as this. Whether it’s the humble thankfulness of “To Be Alone With You” and “Size Too Small” or the triumph of “The Transfiguration,” Stevens’ Christian faith resonates throughout Seven Swans.

The album opens with “All The Trees Of The Field Will Clap Their Hands,” which finds Stevens musing “And I’m joining all my thoughts to you/And I’m preparing every part for you.” Some might read those lyrics with ambiguity, and Stevens is certainly no Bible-thumper, but the Scriptural references elsewhere in the song point to where Stevens is directing his attention. And the unassuming and personal way in which he does so makes it all the more inviting for us to do likewise.

“In The Devil’s Territory” might be the prettiest song ever written about staring down the Beast. Amidst a soaring banjo and organ (not to mention musical saw), and accompanied by the willowy harmonies of Elin and Megan Smith (Danielson Famile, of whom Stevens is an honorary member), Stevens sings “Be still and know your sign/The Beast will arrive in time/We stayed a long, long time… To see you/To beat you/To see you at last.” But the very next song, “To Be Alone With You” finds Stevens at his most humble. Singing “You gave Your body to the lonely/They took Your clothes/You gave up a wife and a family/You gave up Your ghost/To be alone with me… You went up on a tree,” Stevens paints Christ’s humilation in almost Endo-esque terms (a la The Samurai). And “Abraham,” in just a few lines, connects righteous Abraham’s call to sacrifice his son Isaac with a coming Messiah.

As the album winds down to a close, Stevens grows even bolder, and Seven Swans closes on notes both traumatic and triumphant. Seven Swans opens with a solemn banjo progression as Stevens describes the Apocalypse unfolding before him in both personal and cryptic ways. The song’s tone grows increasingly urgent, underscored by the ominous piano that rolls in like ancient church bells. By its end, Stevens is plaintively crying “He will take you/If you run/He will chase you/He is the Lord” amidst crashing cymbals like an Old Testament prophet pleading with unrepentant Israel.

Thankfully, Stevens does not end things on a fearful note, but rather with the triumph of “The Transfiguration,” in which the presence of God is a relief rather than a terror. In his inimitable fashion, he turns this biblical account, where Jesus’ glory is revealed before the Crucifixion, into a reflection on the exact meaning behind of His life, death, and resurrection. As a result, the album ends on a celebratory chorus — “Lost in the cloud, a voice/Have no fear! We draw near!/Lost in the cloud, a sign/Son of Man! Turn Your ear!” — which is as good a summation of the Good News as I’ve heard.

I found it interesting to listen to this song, and the album as a whole, so soon after having seen The Passion Of The Christ. Mel Gibson’s film paints a very stirring and powerful portrait of Christ’s sacrifice with horrific violence and intense drama. And yet, for me, Seven Swans brought about much of the same contemplation and gratitude, if not moreso, only with the barest of whispers.

With his humility and subtlety, Stevens gets it right where so much of the “praise and worship” music out there gets it so very wrong so much of the time. Rather than make huge, sweeping theological statements and generic “feel-good” platitudes, Stevens’ communicates things of the faith in very personal and intimate terms, drawing on darkness and sadness as much as wonder and triumph.

I know that others might listen to Seven Swans and not get any of this, aside from the explicit references to “Jesus” (but even then, they’ll still end up with an album of gorgeous folk-pop). But many of the phrases and images that Stevens’ employs have often moved me to contemplation and yes, even worship, be it the humble realization that closes “To Be Alone With You,” the longing for the Messiah to come in “Abraham,” or “The Transfiguration“ ‘s jubilee. And as one who is often skeptical of the “W word” and the way it’s often tossed around and cheapened within religious circles, that means a very great deal.