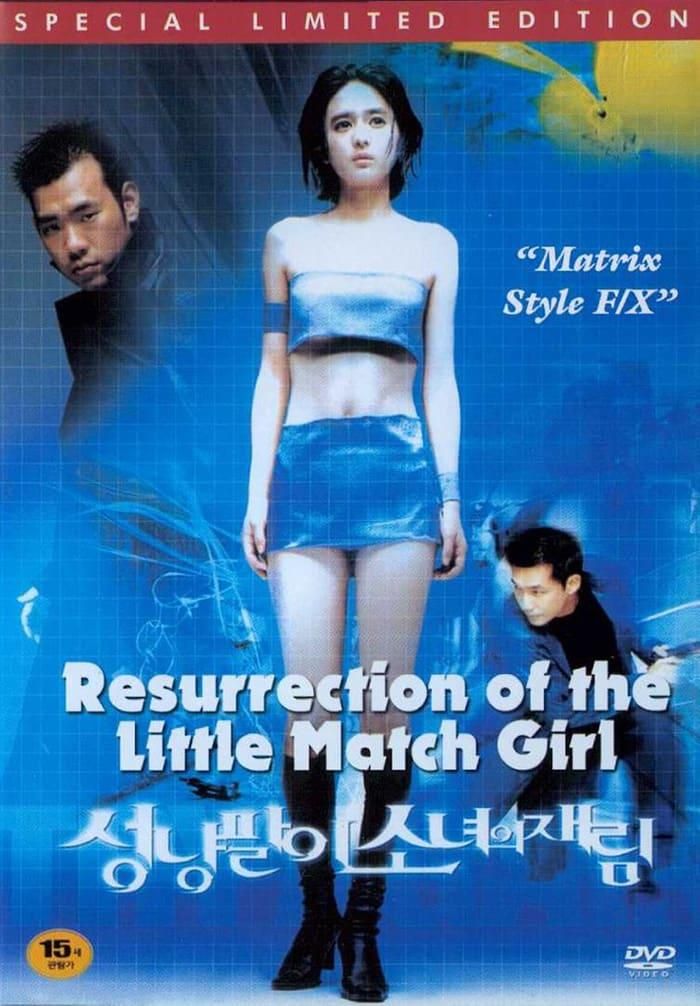

Resurrection of the Little Match Girl by Jang Sun-Woo (Review)

Requiring 10 million US dollars, 4 years, and almost 10,000 extras, Resurrection of the Little Match Girl is without a doubt, the biggest film production in Korean history. It also turned out to be one of South Korea’s biggest box office failures. Having seen the movie twice now, it’s easy to understand why. All of the problems that crop up in Resurrection of the Little Match Girl don’t arise from a lack of anything. Rather, it’s the complete opposite.

The movie’s main character is Ju (Kim Hyun-sung), a young man who spends all of his spare time at the videogame arcade and who dreams of becoming a professional gamer like his best friend Yi. When he’s not at the arcade, he’s either riding around town on his scooter delivering food to ungrateful customers, getting berated by his boss, ignored by his family, or getting rebuffed by his dream girl Hee-mee, who runs the arcade.

After another late night at the arcade, Ju meets a mysterious girl who looks just like Hee-mee, but who is selling lighters. He buys one from her and follows her out of curiosity, only to see her go off with a group of sailors in their boat, presumably to earn money selling her body. As if the movie resets itself, Ju suddenly finds himself back where he started. Noticing a number written on the lighter, he calls it, and finds himself entering a mysterious game called Resurrection of the Little Match Girl.

The object of the game seems rather bizarre. Ju must find the Little Match Girl, named Seongso, and ensure that she freezes to death à la the Hans Christian Andersen poem. But he must be the last thing she thinks of before she dies. Only then will he be able to leave with Seongso for a better place. Of course, Ju isn’t the only one playing the game; there are thousands of players and they’re all better and more deadly than he is. Despite the risk that he may never return to the real world if he fails, Ju starts playing.

As the game progresses, it becomes apparent that there’s more at stake than just winning the girl (so to speak). Also, it appears that Ju is not your average player. System, the omniscient entity that controls the game, believes that Ju is a threat, and endeavors to stop him before he reaches the girl, even hiring Yi as a hitman. Ju is saved by Bangjang, the man who created System. Betrayed by his creation, Bangjang now hides in the game, waiting for a chance to bring it down.

Ju finally saves Seongso. However, after saving her, she turns into a serial killer, mowing down anyone who won’t buy a lighter and becoming a media star (think Natural Born Killers). After a standoff at an abandoned factory, System closes in and takes her to their facilities for reprogramming. Ju must work with Bangjang and a few other allies to infiltrate the, umm, system to rescue the girl because, surprise, he’s fallen in love with her.

Well, so far, so good. It all sounds fairly straightforward, if not just a bit derivative of the The Matrix. But while watching the movie, I found myself understanding why it went over so poorly with the hometown crowd, for several reasons.

First of all, there are times when the movie tries to approach the storyline with tongue firmly in cheek. For starters, the movie is full of video game parodies and references. One of the characters Ju meets is Lara (Jin Xing), a Lara Croft clone who happens to be a mentally unstable lesbian that takes out bad guys while dancing in nightclubs or riding her fur-trimmed Harley Davidson. When new characters appear, we’re given pop-up windows displaying their bios and stats, and when existing characters advance in levels, we see their stats increase. The movie is also kind enough to let us know when Ju moves on to the next stage of the plot/game. Heck, the DVD menus even look like those on an X-Box, so much so that I’m surprised Microsoft hasn’t gotten involved yet.

But it gets more ridiculous. Anyone who has ever watched any old school kung-fu movies might smirk at Ju’s training. Before Ju can invade System, he must undergo a period of Zen-like training to enhance his mental powers; in other words, he must catch a fish without any bait. And there’s also Ju’s secret weapon, a plastic toy raygun named… drumroll please… “The Mackerel” that he controls with his mind.

Secondly, as much as the movie and its website tell us to not take things seriously, it’s hard to do otherwise. Mainly because the movie never stops taking itself seriously. Even when it’s trying to be clever with its video game references (which, admittedly, is a interesting attempt to make the movie more interactive), the tone never feels as lighthearted as it should. Also, if this is supposed to be a parody, why is everyone so wooden and emotionless?

With the possible exception of Lara and a group of bumbling gangsters who chew up scenery like bubblegum, the characters rarely show any emotion. This is especially true of the leads. Ju is nondescript at best, rarely displaying any charisma (which you need to have if you’re taking out enemy soldiers with “The Mackerel”), and Seongso is utterly blank, whether she’s selling lighters or mowing down people in the street.

Third, the movie’s fractured storyline means ancillary plots and characters slip through the cracks, even those that seem somewhat integral to the primary storyline. The whole Bangjang/System thread could’ve been interesting to pursue, if only to find out more about System itself. But System remains completely unexplained. Is it a video game company, a shadow organization, or, as the name implies, a computer system such as an AI? This ambiguity makes it hard to believe they’re that big of a threat. Oh, and we never really find out why System perceives Ju to be a threat, or why Bangjang takes an interest in him.

There’s also a plot involving Seongso, her dead lover, and the gangster who killed him. Before she became the Little Match Girl, Seongso was in love with a rock star named Ga Ju-No. Not that it’s important to the story, or even explained very well in the movie (I had to go to the website to find this stuff out). But it feels like it should be. All we get is a brief flashback when Seongso tries to end it all by breathing in her lighters’ fumes, a flashback which includes a performance by Ju-No’s band playing a tepid, Incubus-style ballad clearly designed to give the movie some “youth appeal.”

But perhaps the most frustrating thing about the movie is its disjointed sense of reality. Of course, being a movie, none of what you see is real. However, the movie takes that concept and runs, piling on layers of reality until you just don’t know how to process anything that takes place onscreen. This could all be an elaborate VR game, or perhaps the game is the true reality and the world Ju knew before the game was false (yet another Matrix reference), or maybe it’s all just an elaborate fantasy driven by Ju’s love for both Hee-mee and for videogames. Maybe it’s all three, or maybe something else entirely, or maybe it’s just a case of the director trying to be too post-modern for the movie’s good.

This “layered reality” approach has been done many times before, by movies ranging from The Matrix and Avalon, and often with better results. (However, I will say that Resurrection of the Little Match Girl was still far better than The Thirteenth Floor, quite possibly the crappiest “layered reality” movie of all time.) Perhaps this disjointed approach is all in line with the Taoist philosophies the run throughout the movie. But it makes for a frustrating experience, and the ending, though warm and fuzzy, lacks any real impact as a result. Apparently I’m not the only one who feels that way, considering the movie’s paltry box office returns (not to mention other reviews and articles I’ve read, which all come to similar conclusions).

So does the movie have anything going for it? Well, from a visual standpoint, you can see where the movie’s big bucks went. Resurrection of the Little Match Girl is filled with all of your requisite splashy visual effects, explosions, big guns, and kung fu combat. But visually speaking, I found the film’s non-action scenes to be far more interesting.

Before Ju enters the game, he inhabits the world of the arcade, a world full of light and sounds, and Jang Sun-Woo’s camera soaks the viewer in it. At times, the garish lighting, exotic music, and camerawork are reminiscent of Wong Kar-Wai’s films, especially Fallen Angels. Whenever Jang’s visuals grow abstract or stylish, either through lighting, film grain, or something else, they’re often quite beautiful and otherworldly — such as Ju’s training session or the underwater embrace that serves as the film’s emotional climax — and do far more to convey a sense of alternate reality than the film’s narrative or clever cultural references. By the film’s second half, though, it’s almost all Hollywood, and the favorite source of material is The Matrix (bullet ripple effects, alpha-numeric waterfalls, and similar sound effects).

According the movie’s website, Resurrection of the Little Match Girl attempted three things: popular entertainment, philosophical depth, and experimental forms (I assume this last item refers to the stylish camerawork, abstract scenery, nonlinear story, etc.). If it had just stuck to one of those, I think the movie’s potential (of which there is a lot, all things considered) could’ve been realized to a much greater extent.

As it stands, the movie is rarely entertaining, the philosophy may be deep but it’s needlessly cryptic, and the experimental forms are never as fully realized as they could be. The movie is far more enjoyable as a bizarre little cult classic, rather than the big, thought-provoking action movie the filmmakers intended it to be. As negative as I’ve been on the movie, I do find it intriguing, but also sadly disappointing. Resurrection of the Little Match Girl could’ve worked as either a popcorn flick for action junkies or a deeply spiritual and philosophical film for arthouse types, but it doesn’t work trying to be both.

It’s clear that the filmmakers’ reach exceeded their grasp here, as the movie literally stumbles over its own excess and ambition. If you read the director’s statements and production notes on the website, you’ll get a better understanding of just what was trying to be achieved here. However, that will probably serve only to make the film’s shortcomings all the more obvious and that “oh, what might’ve been” feeling all the more keenly felt.