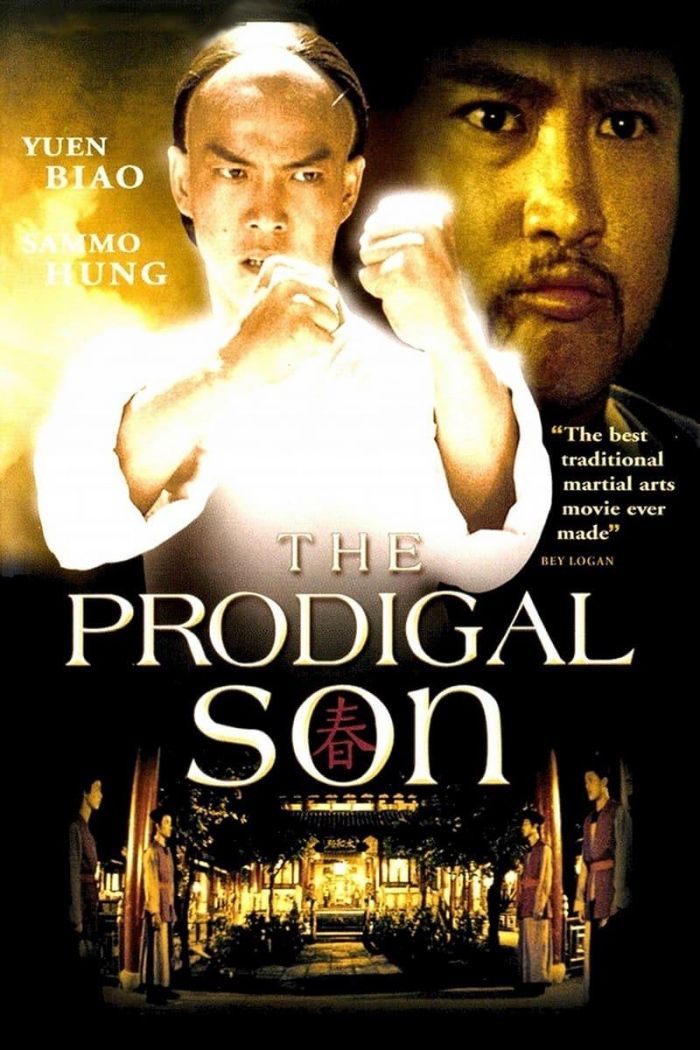

The Prodigal Son by Sammo Hung (Review)

It’s a safe bet to say that I’ve seen more kung fu movies than your average Joe. Granted, I’m no Richard Meyers, but I’m pretty proud of my collection. One thing that I’ve learned, time and time again, is that you must be prepared for anything when it comes to HK cinema. Normal movie rules do not apply, especially if your idea of action movies begins and ends with Jerry Bruckheimer. Oh sure, Hollywood may cop more than their fair share of ideas from Asian cinema (I dare you to find a modern action movie that doesn’t owe half of its ideas to John Woo), but they’ll never be able to match the sheer, well, zaniness that occurs within a good, old-fashioned kung-fu piece.

Take, for example, The Prodigal Son. At first glance, it seems innocuous enough. Leung Chang (Yuen Biao) is widely recognized at the city’s foremost kung fu expert. But the truth is that his rich father fixes all of his fights so that he doesn’t get hurt. Naturally, this makes Chang the laughingstock of the area, though he’s completely in the dark. Now, you might think that this film is heading straight towards the same sort of buffoonery that filled Jackie Chan’s movies during his Young Master days.

However, things get slightly weird when Chang and his friends decide to attend a local Peking opera performance. One of his friends becomes enamored with the lead actress, and decides to make his move on her. Unfortunately for his libido, she turns out to be a man, who quickly makes short work of Chang and his pals. In an attempt to defend his honor, Chang challenges the man, Leung Yee-Tai, to a duel. Yee-Tai makes short work of Chang, revealing his kung fu for the lame joke that it is, and leaving Chang disgraced.

Determined to become a martial arts champion, Chang insists that Yee-Tai take him as his student. The actor refuses, so Chang gets his dad to buy the whole opera (talk about investing for your kid’s future) so there’s no way Chang can be refused. Yee-Tai grudgingly accepts Chang as his student, but still refuses to teach him any kung fu.

Yawn… so far, very little happens. Despite all of the comedic setup, there’s very little laughworthy material. It’s more goofy than anything else, what with the music that would make Sid and Marty Kroft green with envy and the overly effeminate Yee-Tai. In fact, you start to wonder if anything is going to happen at all. The opera journeys to another town and gets ready to perform. However, when Chang is mistaken for an actor who has been having an affair, things start to pick up. Yee-Tai makes short work of the angry husband and his goons, much to the interest of Lord Ngai, a local nobleman who has been looking for a worthy opponent.

Ngai invites the whole opera troupe to his house, hoping to challenge Yee-Tai to a match. In one of the film’s finest kung fu sequences, Yee-Tai proves that he’s more than a match for Ngai. However, he also reveals his asthma affliction. Being honorable, Ngai refuses to beat him. However, word of Yee-Tai makes it back to Ngai’s father. Like Chang’s father, he doesn’t want any harm to come his son, and like all good fathers would do in his situation, he arranges to have whole opera troupe killed.

It’s here when the film just goes out the window. The troupe is massacred in the middle of the night, a slaughter that’s fairly graphic — women and children getting their throats slit (with nice matching sound effects), limbs getting shattered, and everything going up in flames. What makes it even more impacting is how unexpected it feels. Up until this point, the film had been fairly innocuous and frivolous, and then it just explodes into a bloody slaughter that literally smacks you upside the head and leaves you reeling.

But, just as suddenly, we’re back to Goofyland. Yee-Tai and Chang escape into the countryside, where they shack in a farm. Conveniently, they just happen to be now living next door to Yee-Tai’s brother, Wong (Sammo Hung). Compared to the effeminate Yee-Tai, Wong is blowhard and a buffoon who enjoys homosexual jokes about Yee-Tai, and who also just happens to be one heckuva calligrapher. After an initial misunderstanding (Wong’s daughter thinks Chang is trying to sexually assault her, although Chang is merely going after a chicken), an uneasy truce is struck.

Eventually, Yee-Tai and Wong begin to teach Chang kung fu (though both think the other’s style is inferior). And there’s still plenty of goofy humor (especially Wong’s “taking a crap” style), and some patently crude humor (mostly at the expense of Yee-Tai, who is commonly referred to as a “fairy” and “faggot” by the boorish Wong). But Yee-Tai’s asthma gets the best of him, and Chang is forced to return home so his master can heal up.

Unfortunately for Yee-Tai, Ngai is waiting for him, and his men still have orders to protect him at any cost. This leads to your always popular “you killed my master” final battle, which takes place at some conveniently located Mayan ruins. Like the opera massacre, the final battle is surprisingly brutal and savage (oozing wounds, split-open heads, and other goodies), and like the opera massacre, it comes out of nowhere… and it leaves you reeling.

By now, there’s no way around it; The Prodigal Son is a bipolar movie. One minute, you’re groaning at the movie’s lame/crude/bizarre/goofy humor, and the next you’re peeking out between your fingers at the violence. I’m not sure if this sort of manic-depressive pacing was intentional or not, to keep the viewer off-balance, or if that’s just the way it turned out. Whatever the case, its the movie’s best feature, as well as its Achilles Heel.

Everything feels out of proportion, with such outrageous emotional swings. Unfortunately, there’s nothing in the actual plot that keeps you riveted. Despite the film’s best efforts, the plot feels incredibly hackneyed and clichéd, right down the big final battle (a staple of martial arts cinema to be fair) which also feels anticlimactic. Ngai is innocent of Yee-Tai’s death (it’s his father’s fault) but Chang insists on fighting him anywise; there is no major baddie in this film.

On top of that, the performances are nothing outstanding, merely passable at best. Biao has never impressed me with his acting; he’s an agile enough fellow, but he lacks the charisma necessary to carry off the film. It doesn’t help matters when he’s constantly upstaged by the rivalry between Yee-Tai and Wong, or the movie’s huge mood swings.

The Prodigal Son has been called one of the most authentic martial arts movies of all time, and that might be true. There’s certainly enough bloodshed and pain to go around for all involved; noone leaves a fight unscathed or unscratched. And there are impressive martial arts sequences sprinkled throughout the movie. But that doesn’t save the film from its unsteady nature. Sure, it’s worth watching just for the sheer delirium of it all. But between the inane gay jokes, slit throats, sexual double entendres involving poultry and portly girls, decapitations, the lost H.R. Pufnstuf soundtrack, and senseless beatings, just don’t expect a any of it to make sense.

But at least you’ll be able to claim you saw it… and that’s worth something in my book.