Primer by Shane Carruth (Review)

It’s a shame that, in recent years, the term “sci-fi” has come to mean lots of explosions, aliens that look like humans with bad cases of acne, wicked cool spaceship designs, formulaic plots, and CGI budgets that are bigger than most countries GNP. Films such as the Star Wars series (especially the prequels), Independence Day, Lost In Space, The Chronicles of Riddick, Wing Commander, and even the recent Star Trek films are largely to blame for this. Sure, they may be great as popcorn entertainment, but anyone looking for something with a little more substance will be left lacking.

Thankfully, there are sci-fi films that are more challenging, that don’t necessarily resort to whiz-bang special effects to blow the viewer’s mind but rather, do so with the ideas and concepts with which they wrestle. Films in this category might include Blade Runner, Pi, A.I. (up until the last half-hour, that is), Dark City, The Matrix (and to a lesser extent, its sequels), and Avalon.

Primer, the assured first-time effort from writer/director Shane Carruth falls squarely in the latter category. This is a film that is all concept, and is so in a very unassuming and subtle manner (read: no special effects or CGI). It’s not a perfect film — there are moments where it seems as if the film is a little too obtuse and vague for its own good — but sci-fi fans looking for something with a little more substance, not to mention a brainteaser or two, are in for a treat with this one.

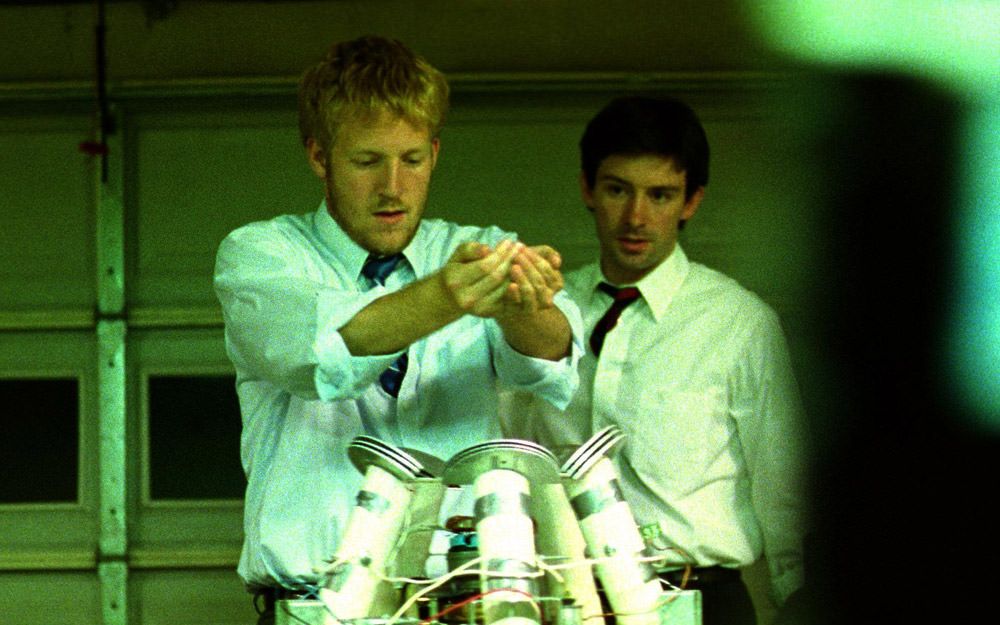

Aaron (Carruth) and Abe (David Sullivan) are two friends who work out of Aaron’s garage making computer parts with a couple of other buddies. It’s clearly a homebrew operation (they spend their nights fulfilling orders at the kitchen table), and while business is good, it’s clearly not enough for the ambitious group. And it’s clear that computer parts aren’t their real focus. Their real focus is a strange device that is spoken of only in hushed tones and cryptic phrases. As the film progresses, we learn enough to surmise that they’re trying to build a cold fusion device, one of physics’ holy grails.

Unfortunately, the group is rather divided as to how to proceed. Aaron and Abe have their clear goals, whereas the other two want to go a more public route. The group splits unofficially, and Aaron and Abe are left working alone in the garage, skipping work whenever possible to put time in on the device. Soon enough, they have what might be a working prototype, only to discover that they might have something more on their hands, something much more. They might just have a time machine.

At first, the movie seems rather linear and easy to track, but as is fitting for a movie about time travel, the plot starts to go haywire pretty soon. Soon, we no longer know if what we’re seeing onscreen is happening, or if it did happen, or if it’s going to happen. Are the Aaron and Abe we see the “real” Aaron and Abe, or merely two of their dopplegangers? Are the choices that we see the characters make free, or were they “programmed” in advance by someone or something else? And what’s with the voiceover, a seemingly God-like voice that narrates that proceedings?

I apologize if this all seems rather vague, but to discuss the plot in any greater detail would a) spoil things that are best discovered while watching the movie and b) render this review an unintelligible mess what with all of the twists, turns, and paradoxes bandied about. There are a handful of moments where the film is a little too vague, and certain events happen that seem a little too convenient and contrived. But again, repeated viewings may reveal a little method behind the madness. Thankfully, since the film only runs 78 minutes, it’s easy enough to go back and rewatch the film and try to pick up where things went a little off for you.

Despite it’s few missteps, there is an awful lot that Primer has in its favor, beyond just an intriguing plot. For starters, writer/director Carruth directs with a very steady hand. Some of the shots are a little too vague, showing us just enough to be intriguing but not enough to not be maddening. But though the film was shot for a mere $7,000 (yes, seven thousand dollars), and Carruth taught himself everything about filmmaking, the film certainly doesn’t suffer for it, maintaining a very cool, mysterious atmosphere throughout.

Performance-wise, don’t expect Oscar-quality acting, but that’s not the point. This is an “idea” film, and as such, is very dialog-driven. The cast do a fine job as such, looking less like actors trying to be normal guys and more like normal guys portraying themselves.

As a sci-fi fan, I was very relieved that the film didn’t suffer from the “Star Trek” condition, i.e. needless techno-babble. While there is some science-speak throughout the movie, nowhere did I hear stuff that sounded obviously made up, hackneyed terms such as “inverted neutrinos,” “temporal matrices,” “chronotronic beams,” and other such drivel.

The relative absence of science-speak might frustrate any physics teachers watching the movie, but for us laymen, it creates a nice ambiguity concerning the characters’ inventions, which makes it much easier to suspend disbelief and focus on the questions being asked by the film. This is of great benefit to people who might normally roll their eyes at the first CGI-enhanced temporal anomaly, or the first mention of some obviously imaginary subatomic particle or technological device, or some other such nonsense.

Primer can be maddening, and a little too vague and obtuse. (If you thought Memento was bad, you ain’t seen nothin’ yet.) However, its strengths greatly outweigh its weaknesses, and the questions it asks are sure to keep you up at night. Questions such as: What is free will? Is it possible to change a person’s destiny without them even knowing it? If one starts messing with time, what responsibility does one have to make sure things go right? Or will fate always work itself out? And if so, at what cost? What do you do about choices seemingly made completely out of your control?

It’s rare to see such high-minded stuff played out in as simple and unassuming a manner as it’s done here, which makes Primer all the more intriguing.