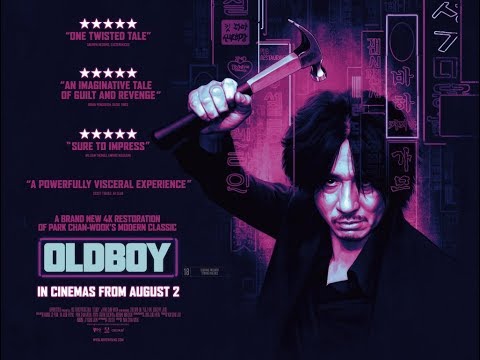

Oldboy by Park Chan-wook (Review)

Whenever I discuss movies with people, and we start mentioning some of our favorites, it’s inevitable that I’ll get asked why I like Asian cinema as much as I do. 4 or 5 years ago, I would’ve replied as a growing devotee of kung fu and “heroic bloodshed” movies, that the action in Asian cinema was just so much more exciting and thrilling than its Hollywood equivalent. Of course, as my knowledge of Asian cinema has increased in recent years, my view of it has become more, shall we say, realistic, in that I realize that Asian filmmakers put out just as much crap as their Hollywood contemporaries (heck, Wong Jing alone puts out enough crap for any 5 Hollywood filmmakers).

However, the question still remains: why do I like Asian films as much as I do? And I think the basic answer is still the same as it was back when I first discovered the movies of Jackie Chan, Jet Li, and John Woo. I watch Asian films because I get to see things — be it action scenes, storylines, characters, etc. — that I would never see, in a million years, from a Hollywood film. In short, I like Asian cinema because of films like OldBoy.

OldBoy has been receiving a fair amount of buzz, due to the praise showered on it by pundits like Harry Knowles (who named it his 2nd favorite movie of 2003) and to it’s strong showing at this year’s Cannes Film Festival (where it received second place honors). However, I highly doubt that this film will make it to American shores. It’s probably too raw and uncompromising in its depiction of vengeance and human depravity, far too intelligent to paint such things in mere black and white terms, and far too sympathetic in portraying its characters as damaged, tragically flawed people rather than as simple “heroes” and “villains.”

In a plot that feels lifted from a Kafka novel (actually, it’s based on Tsuchiya Garon’s manga), Oh Daesu is returning home on his daughter’s birthday when he suddenly wakes up in a dingy room that will serve as his prison for the next 15 years. Unable to escape and denied even the ability to kill himself (everytime he tries, his unknown captors intervene), Daesu begins to lose every shred of what makes him human. His only companion is a television set, which keeps him abreast of world events (and informs him that his wife has been murdered and that he’s the main suspect). With everything stripped away, he becomes obsessed with just one thing: trying to figure out who did this to him, tracking them down, and killing them.

And then, just as suddenly as he was imprisoned, Daesu is released back into the real world, more a beast than a human being (he even refers to himself as “Monster”). While trying to figure out where to start on his “roaring rampage of revenge” (to borrow a Tarantino-ism), his captor makes the first move, beginning a game of cat and mouse that has Daesu running against the clock and through his youth to unravel just why he was imprisoned, and perhaps more importantly, why he was released.

Altogether, OldBoy is easily writer/director Park Chan-Wook’s most accomplished, stylish, and brutal film to date (at least, of those widely accessible on non-Korean shores). While his previous films, Joint Security Area (a gripping film about the friendship between South and North Korean soldiers that launched Park into the limelight) and Sympathy For Mr. Vengeance (a similarly-themed film about a kidnapping that goes horribly, horribly wrong) were both good in their own ways, OldBoy is in a completely different league.

Park has often been compared to David Fincher, and OldBoy does bear some similarities to Fincher’s style. The plot is somewhat reminiscent of The Game, and there are certain stylistic flourishes that are similar to Fight Club (one scene in particular reminds me of Fight Club’s IKEA apartment scene). And of course, there’s the unrelentingly dark tone of the film. However, Park isn’t merely cribbing from some hip director, and OldBoy contains some truly stunning scenes.

In particular, the movie’s portrayal of violence is quite jarring. During his imprisonment, Daesu resorts to shadowboxing and watching matches on the TV. When he is released, he finds these skills serve him quite well in the real world. Indeed, his ability to absorb pain seems almost superhuman, and Daesu absorbs a lot of punishment.

In one of the movie’s most breathtaking scenes, Daesu takes on a group of thugs in a cramped hallway. Shot in one, continuous tracking shot, Daesu and the gang go at it, and as the camera refuses to cut away, it becomes that much more torturous and draining to watch. This is a far cry from the hyperstylized bloodshed of the Kill Bill movies. Violence is never depicted as a thrilling thing, but as a necessary thing for Daesu, if only because that’s all he has left. Make no mistake… OldBoy is a harsh movie, but the physical violence is nothing compared to the emotional violence and wretchedness that ensues.

There is one other thing that Park has that Fincher doesn’t — the acting of Choi Min-sik (Failan, Shiri). There are strong performances from all of the primary cast — Yu Ji-Tae (Ditto, Attack The Gas Station!) actually makes Daesu’s haughty captor a tragic figure at times, and Kang Hye-Jeong (Nabi) is appropriately fragile as Mido, the young woman inexplicably drawn to Daesu — but this is first and foremost Choi’s movie (for which he won top acting honors at Cannes 2004).

His performance is simultaneously riveting and revolting. Not just in the things that he does (such as devouring a live octopus), but in the whole persona he projects. It’s almost frightening to think of what he might have tapped into to get into character, but when Daesu is released from prison, you are convinced you’re looking at a beast dressed up in a black suit and sunglasses.

When he first appears as “Monster,” there’s an intensity in his character that could make a whole squadron of Green Berets wet themselves. However, Daesu transforms before our eyes as the movie progresses, becoming at times heroic and pathetic, pitiful and repulsive. I was truly struck by Min-Sik’s incredible performance in one of the final scenes, when Daesu finally realizes what’s been going on and is reduced to grovelling at his captor’s feet — it’s one of the most gutwrenching scenes I’ve watched all year. In all honesty, I can only think of one or two Hollywood actors who would dare push themselves to those limits, who would even be able to imagine conjuring up that sort of intensity.

However, OldBoy isn’t perfect. Park frontloads the movie quite a bit, such that when all is said and revealed, the final twists seem a bit underwhelming (though executed quite nicely). But even having said that, you probably won’t see a more intense film this year (if you own an all-region player, that is). Much has been made of the film’s bleakness (though I personally found it far more engaging than Sympathy For Mr. Vengeance), and some have even called the film sadistic, saying that Park merely seems to want to inflict as much misery and revulsion on the audience as possible.

But as I look back on the film, I find myself thinking how easily this movie’s story could’ve come from a Shakespeare play, or even (at the risk of sounding sacreligious) the Bible. There’s something rather Old Testament-y about this story to me, with its portrayal of vengeance, depravity, and forgiveness (or what happens when forgiveness is absent). However, I think that what might get stuck in most people’s craw is how Park refuses to condemn or condone his characters.

Even the movie’s antagonist is given a moment of tragedy, without being sappy or writing off the horrible things he’s done. And Daesu is never portrayed in a blameless light, despite being the film’s “hero.” Whenever Daesu gets a chance to lash out at his captors, it isn’t with an adrenaline rush but rather a sad sigh that things seemed almost fated to turn out this way. Early in the movie, Daesu wonders if he’ll ever be able to leave the “Monster” behind. But by the movie’s end, Daesu has lost a part of himself, literally and figuratively.

In the end, I’d be tempted to go so far as to say that Park actually, truly cares about his characters, even the worst of them, and in doing so, reveals that they may not be as far removed from us “real” people as we’d like to think. We all have beasts lying just below our skin, just waiting to go on a “roaring rampage of revenge” of our own, for something to set us off. True, we might not take on a whole gang with nothing more than a hammer, but we do have our limits — and when pushed past them, something will snap and we’ll all become monsters in our own right.