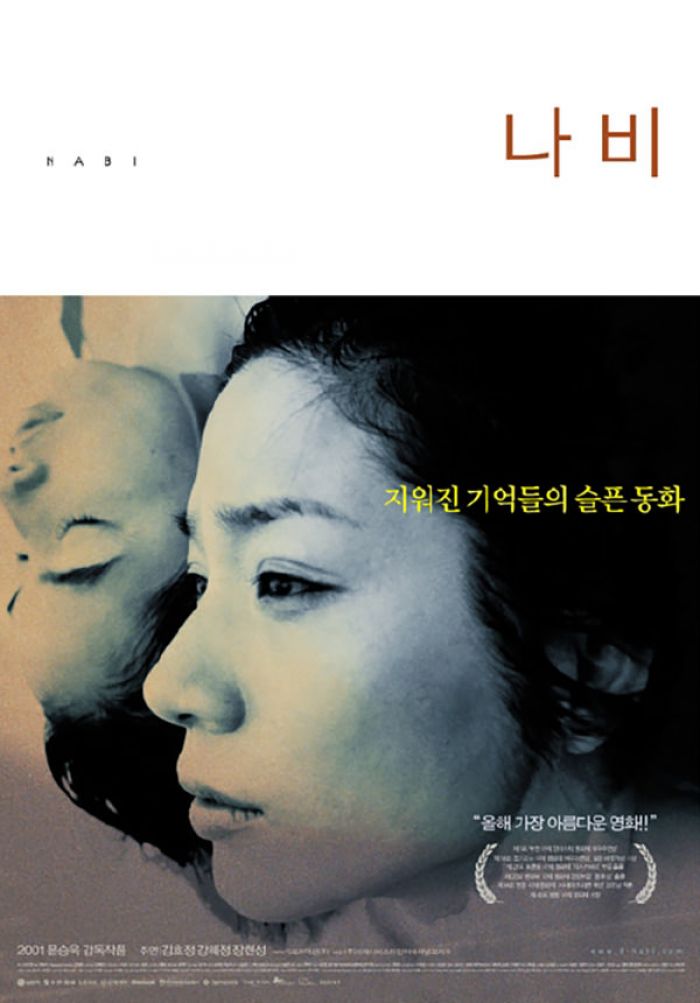

Nabi by Moon Seung-Wook (Review)

Memory is a big subject in movies these days, due in large part to post-modern thrillers like Memento and surreal mind-trips like the brilliant Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. In 2001, Korean writer/director Moon Seung-wook probed similar territory with his feature-length DV debut, Nabi (trans. The Butterfly).

If you’re at all familiar with Korean cinema — currently, one of the world’s great treasure troves of fine drama and action pieces — Nabi might come as a bit of a shock, for a few reasons. For starters, its storyline and execution has more in common with certain European arthouse directors, specifically Krzysztof Kieślowski, than it does with any of Moon’s countrymen.

Set in the not-to-distant future — sometime after 2001 to be precise — Nabi tells the story of Anna Kim (Kim Ho-jung), a Korean woman who has lived in Germany for most of her life. Tormented by something painful in her past, she has returned to Korea to catch the so-called “Oblivion Virus” that is sweeping the country, erasing the memories of those who come in contact with it.

Because it’s next to impossible to know where the virus might strike next, an entire “tourism” industry has sprung up around helping people find it. “Tourists” hire guides to lead them to the location of the next outbreak, a la Tarkovsky’s Stalker, which is announced by the presence of white butterflies, (hence the movie’s title). Upon her arrival, Anna meets up with her guide, a teenager named Yuki (Kang Hae-jung), and Yuki’s driver, a sullen man who goes by K (Kim Hyun Sung).

Although the film has a rather dystopic, possibly even post-apocalyptic setting (the city is awash with acid rain and suffers from an epidemic of lead poisoning), Moon wisely avoids making this some sort of Blade Runner-esque sci-fi piece. There is little, if any, technical discussion about the virus, how it works, or where it came from. In fact, Moon seems completely unconcerned with any technical details whatsoever. Instead, he focuses solely on the relationships between his three main characters, all of whom are broken and lonely individuals.

Anna is obviously so, running away from a painful past and willing to throw her entire life away in hopes of starting over. K grew up in an orphanage and doesn’t know his family or his real name. He spends all day driving around town in his cab, hoping that some fare might recognize his baby photo on the dashboard. Of the three, Yuki seems to be the only bright spot, but she’s also 7 months pregnant, and the life of a guide is obviously taking its toll on her and the unborn child.

Of course, nothing goes according the plan. Every time they draw near to the virus’ location, something goes wrong, forcing Anna to spend more time than she would like with this motley crew. In shades reminiscent of Kieślowski’s wonderful Blue, Anna slowly finds herself getting drawn from her shell as she finds herself taking care of, and getting cared for by, Yuki, and later, K. As much as Anna would prefer to remain a loner and throw away her memory, she can’t help but be drawn to Yuki’s plight, and to the hope that the young girl might somehow avoid the same tragedies that have befallen her.

Korean cinema is well-known for its drama. No one, it seems, does it better these days. But go into Nabi expecting the typical melodramatic situations and overwrought conclusions, and you’ll probably be disappointed. The film has a very disjointed, even awkward feel to it, punctuated by long stretches of silence and impassive faces, and although the film does manage to wrap up some loose ends, it leaves just as many open and ambiguous.

Korean cinema is also well-known for its gorgeous and glossy visuals. Nabi boasts a very distinctive visual style that’s more in the neighborhood of Wong Kar-wai (particularly Fallen Angels and Chungking Express) than any of Moon’s fellow Korean directors. Originally shot on DV and then converted to film, Nabi’s look lands somewhere between a documentary and home video, lending the film an incredible immediacy.

While some might decry DV for lacking the richness of film proper, Moon captures some stunning imagery with his camera, most of it involving water somehow. In one amazing scene, Anna, Yuki, and other tourists cavort in the hotel swimming pool. The underwater shots are simply breathtaking, and the DV look only adds to their surrealism. When the characters have to give each other showers to cleanse the effects of acid rain, the scenes have a surprising intimacy that in the hands of a lesser director would be solely prurient. And the film’s climax, when Yuki gives birth in the ocean with Anna and K’s help, etches itself in your memory, the trio struggling in the waves while the harsh light of sunrise surrounds them.

After spending several days diving headfirst into various chopsocky, kung fu, and samurai films — many of which were completely over the top in ways that only Asian film can be — I really needed something with more depth, something contemplative and substantial that I could lose myself in. Nabi filled the bill quite nicely. While certainly unconventional and obtuse any way you look at it, it still does a wonderful job of drawing you into its haunting visuals, and more importantly, into the tragic lives of its characters at that crucial moment when hope and renewal become a possibility.