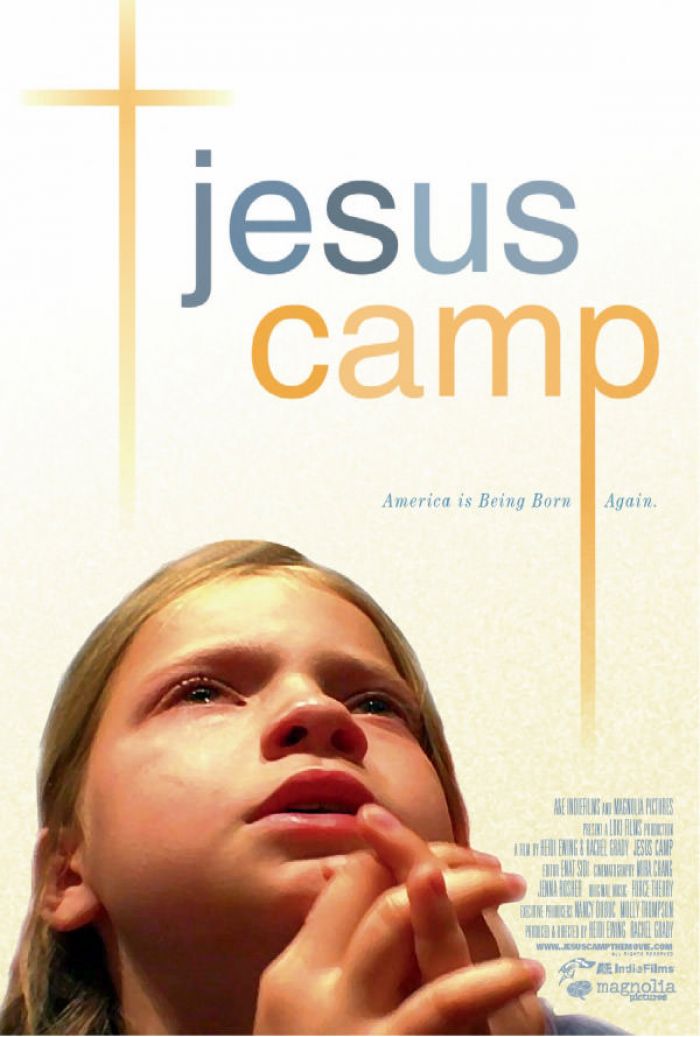

Jesus Camp by Rachel Grady, Heidi Ewing (Review)

There’s a scene part-way through Rachel Grady and Heidi Ewing’s Jesus Camp where Levi, one of the children who attends the titular camp, and who is already a burgeoning preacher at the age of 13, claims he can always tell when he’s around non-Christians. There’s something off about them, he says, something that makes him feel sick.

Some might find such a statement to be rather horrifying and judgmental, most likely the result of the sort of parental indoctrination that gives Richard Dawkins the heebie-jeebies. Others might find the young man’s naïveté laughable. For myself, it brought on a curious form of nostalgia.

Born into a predominantly Christian family and raised with Christian ideas my entire life, and having attended church schools and regular youth group meetings, I often had very similar things to say about those who existed outside my Christian bubble. That all came crashing down when I began attending public schools. For the first time in my life, I had friends who weren’t Christians. I had friends who held beliefs directly opposed to much of what I had been taught, who believed and practiced paganism and witchcraft, New Age spiritualism, agnosticism, and atheism.

My ministers and teachers had taught me that such people were going to hell in a hand-basket unless I made sure my witness was infallible, I didn’t engage in sinful behavior, and I lived a righteous life. There was one problem with that approach: these hell-bound friends of mine were, in some ways, much better kids than many of my Christian peers.

The Christians I knew were often self-righteous and haughty, if not just plain mean, and I knew a number of them were already fooling around with sex and alcohol. My friends, on the other hand, were far better kids by any particular moral standard. They were nicer, smarter, better-behaved in class, and much more considerate of others — after all, us nerds, dweebs, and misfits had to stick together.

When I heard Levi say those things, I found myself feeling a great deal of concern for the young man. I couldn’t help but wonder what would happen when, not if, he had an experience similar to mine. One can only stay inside the Christian bubble for so long before the real world starts encroaching. It could be the first job he has, where he’s forced to work next to non-Christians. Or when he goes off to college, or somewhere further on down the line. But it will happen. And how would his faith, a faith capable right now of making such blanket statements, handle that shock to the system?

Some of my Christian friends couldn’t take it, and became “backsliders,” to use the Christian parlance. Others retreated even further into their bubbles, only to fall even more at a later date. And some, like myself, decided to take the more difficult path, to seek some sort of balance — to be in the world, but not of it.

Of course, “a curious form of nostalgia” wasn’t the only reaction that I had during Jesus Camp. Indeed, if you come from anything resembling a Christian background, it’s impossible to not experience a jumble of conflicting emotions.

There’s a nervous kind of laughter when the youngsters try their hand at street evangelism with a blend of optimism and naivete. There’s respect for the conviction, passion, and creativity that Pastor Becky Fischer — the woman behind the “Kids On Fire” camp — and her staff bring to their mission of teaching and training children. There’s admiration for these children who are willing, at such a young age, to live for their beliefs despite their peers’ ridicule. There’s a certain amount of horror when watching tactics employed on impressionable children that do, quite frankly, verge on manipulative. And there’s some fear that folks who might not be aware of the complexity present within American Christianity will walk away with a too-simple mental picture.

The filmmakers are certainly to be commended for the extent to which they allow all of the film’s subjects — Fischer, the children, their parents — to speak for themselves and present their beliefs. And the subjects of their documentary, with the notable exception of Pastor Ted Haggard — yes, that Ted Haggard — have all responded favorably towards their depictions in the film. And it’s obvious from interviews that the filmmakers hold their subjects in some high regard.

However, the filmmakers fail to make a strong distinction between Pentecostalism and Evangelicalism, that not all Evangelicals are Pentecostals. At the risk of sounding divisive or dismissive of Pentecostalism, the truth is that there has been long-standing debate within American Christianity concerning various aspects of Pentecostal theology. But little of this comes across in the film. Unless you’re already aware of these serious debates, it is very easy to come away from the film with a very simplified version of the reality of American Christianity, to make assumptions that are, quite simply, false.

In their response to this particular criticism of the film — which was primarily made by Haggard — the filmmakers have asked why folks don’t “take this film as an opportunity to discuss differences and similarities amongst Evangelicals and the various styles of worship and communication?” The same question could be asked of them. Simply put, why didn’t they feature Christians from other strands of American Evangelicalism, and their doubts and concerns? Why doesn’t the film provide any information concerning the “differences and similarities amongst Evangelicals”?

The only contrary voice in the film belongs to radio talk show host Mike Papantonio, who appears occasionally throughout the film to voice his concerns about the growing political power of the Christian Right. The problem is that his segments contain language that, in its own way, is just as inflammatory and alarmist as the language of Fischer et al. that he criticizes.

It could be argued that containing too many voices might have distracted from the film’s central subject — Fischer, her children’s camp, and the children who go there. And that is certainly a valid point. That being said, as someone who came from a background that, while not Pentecostal, was in many ways very similar to what was portrayed in the movie — so much so that I knew the words to the songs being sung and distinctly knew what the kids were going through as they “rededicated” their lives to Christ and renounced worldly influences — I found myself longing for more context, more info, and frankly, a bit more substance.

So what will be the ultimate fallout if you see the film? It will probably mirror whatever impressions and prejudices you brought into the theatre with you. There will be many for whom the film will simply reinforce their fear that Evangelical Christians have this massive conspiracy to change the United States into a theocracy. There will be some for whom the film becomes fresh fodder for ridicule and slander, rather than understanding and dialog. There will be some who find it to be an embarrassment of the faith. And there will be some who see it as a powerful tool that God can use to spread the Gospel.

As for myself, the film, with its emphasis on these children and how they were being trained, arrived at a unique time, as my wife and I begin to consider starting a family of our own. And obviously, if we have children, one of the big questions facing us is this: how do we raise up our children with those values that we believe to be true, that have brought so much meaning and enrichment to our lives, but in a manner that is compassionate and understanding?

Or, to put it another way, how would we train our children without indoctrinating them, without compelling them to think with the stark, black-and-white distinctions that have been so much a part of American Christianity, and which I myself have had to wrestle with time and again. How do we impart values and yet reinforce the idea that ultimately, the choice is theirs. Is that the desirable method? Is it even possible?

These are thorny questions about complex, life-changing issues, and simple answers simply won’t suffice. Even though Jesus Camp does, unfortunately, simplify the issue a bit too much, that fact that it causes me to ask such questions, ultimately makes me glad that I’ve seen it. Even if I found myself cringing at times, by both the actions of the film’s subjects, and the film’s oversimplification of those subjects.