Cube 2: Hypercube by Andrzej Sekuła (Review)

What happens when you make a movie about a theoretical math construct? You end up with a movie that works only on a theoretical level, and even then, only barely. That’s exactly what Hypercube turns out to be, a completely arbitrary mess that never feels like anything other than an excuse for the filmmakers to whip around some esoteric math concepts with little regard for plot, continuity, or logic.

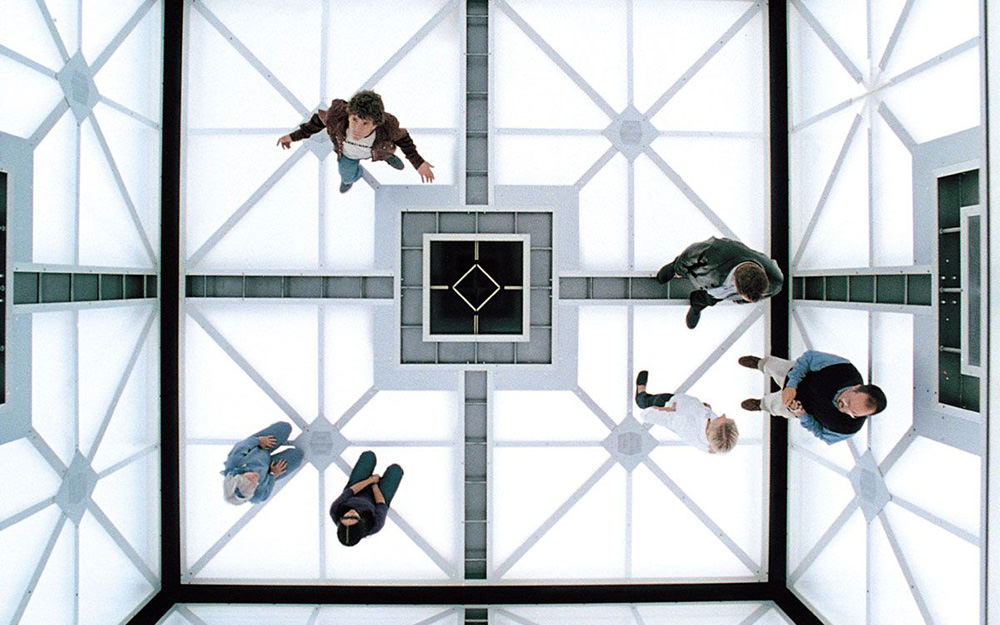

If you’ve watched the first Cube movie, the basic premise of the sequel is identical. A group of seemingly ordinary strangers wakes up in a maze of mysterious rooms. There’s a blind girl, a psychotherapist, a programmer, a lawyer, a private investigator, a senile old lady, and an inventor. As they wander from room to room, trying to figure out how they got there and how they can get out, they find themselves in an environment where even the basic laws of physics don’t seem to apply.

They’ve been placed inside a “hypercube,” a construct that appears only in theoretical math. For those of you who haven’t passed 8th grade geometry, a cube has three dimensions — height, width, and depth. A hypercube (or tesseract, as it’s also called) adds a 4th dimension, either time or some other spatial dimension. As the group discovers, they can no longer trust their own perceptions of space and time, for each room seems to be playing by its own rules.

However, our band of heroes are *gasp* not at all what they seem. All of them have some connection to the hypercube, and a series of shocking yet very convenient revelations are made throughout the movie. The senile old lady just happens to be a theoretical physicist who helped devise the concept of the hypercube, the programmer just so happens to be involved in a lawsuit involving a company that may be responsible for the hypercube’s construction, that company might be the biggest weapons manufacturer in the world, and so on.

After awhile, it seems almost silly how conveniently things begin to unfold. Those shocking revelations seem almost laughable at how well they serve to advance the plot, as everyone seems to have some secret knowledge that they didn’t want to share at first out of paranoia.

Concepts like quantum teleportation, quantum chaos, parallel universes, and whatnot are tossed about with abandon. And believe it or not, everyone seems to know what those terms mean, having just read an article or book on the subject. While I’m not exactly brushed up on my higher mathematics, the way those terms were employed seemed rather willy-nilly, more concerned with sounding cool and mysterious than scientifically accurate.

The movie’s opening moments have some measure of tension, as the characters find themselves working together to get out of one predicament or another. This, however, lasts only for about 15 minutes or so before you start wishing for something shocking to happen. At least the first movie had clever booby traps (the opening scene is especially cool in that regard) which added an element of danger and kept things unpredictable.

Hypercube replaces those booby traps with crappy CGI and bad camerawork. And Hypercube grows more predictable as it continues, to the point where it’s so obvious who is going to die that they might as well be wearing a red shirt. As a result, any creepiness that the first movie possessed is completely absent.

But the most disappointing aspect of the movie is just how arbitrary it all seems. The first movie, as implausible as it was, at least had a set of rules governing how and why things happened. I can’t help but wonder if the filmmakers chose to set the sequel in an environment without physical or temporal laws just so they could disregard pesky things like logic, continuity, and closure. But even that backfires on the movie. Theoretical math concepts won’t save a movie from plot holes, and as a result, my roommates and I spent a good measure of time after the movie was finished pointing out the flaws in its logic.

The film’s ending proved especially irksome. The movie insisted on playing without rules, that is, up until the last 5 minutes. One final plot twist takes place, and yet it completely backfires because it relies on a sense of logic the movie spent so much time trying to dismantle. The movie even tacks on a little government conspiracy bit that could’ve come from any bad “X Files” episode and sets the stage for a second(!) sequel.

The first Cube movie was a perfect example of a great concept saddled with bad acting and dialog. But Hypercube goes way beyond that. It takes a concept that doesn’t even exist outside of math books and tries to turn it into something puzzling and captivating. But the movie never feels like anything but a copout, an interesting premise chosen only because it would let the filmmakers do whatever they wanted without having to explain anything to the viewers.

It’s almost as if the filmmakers stumbled across the concept of the hypercube and, after a few beers and bong rips, decided that “Hey, this would make a really cool movie.” They conceived a couple of stock characters (raise your hand if you didn’t know who was going to snap and turn into a psychopath by the movie’s end), built a simple set, and started filming without realizing that they still didn’t really have a movie. All they had was a concept, and one that doesn’t even really exist.