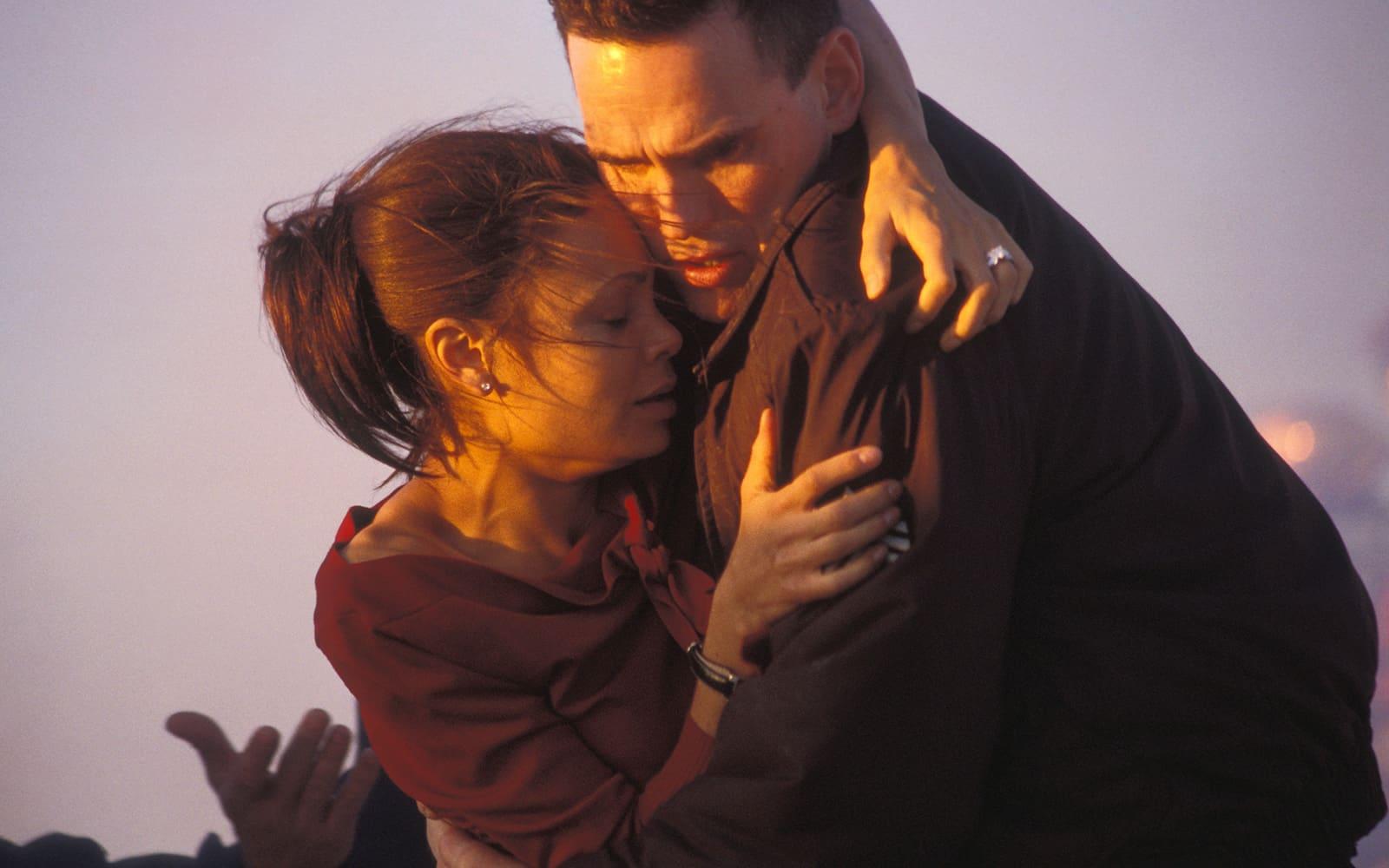

Crash by Paul Haggis (Review)

Crash is one of the most brutal films I have ever seen. This seems a strange thing to say, considering Crash is relatively low on physical violence in comparison to many other recent movies. But the brutality, for the most part, lies not in gruesome murders, but rather in the dialogue of its racist cast of characters. Each and every racial slur seems more harsh, more violent, and more shocking than any of the bloody gorefests to be seen in the next theater over. For this unbridled bigotry reveals a certain something that most horror films and R-rated flicks cannot — the ugliness of human nature.

Why does it come as such a shock, these “niggers” and “crackers” and “Osamas”? Racism, that distinctly American problem, happens all the time. It comes as a shock, then, because it is brought to the forefront, rather than hidden underneath jocular expressions or a quiet demeanor. Racist remarks are most often left unspoken. Here, however, the viewer is assaulted with slur after slur, prejudice after prejudice, most likely leaving them feeling beaten and dejected.

This is the desired effect of Crash. Written by Paul Haggis (of Million Dollar Baby fame) and Bobby Moresco, it follows around several distinct and diverse Los Angeles residents who, within the course of two days, all manage to interact with one another, with mostly dire results. Nearly all of the characters carry with them some sort of racial or economic prejudice, resulting in situations akin to car accidents in their explosiveness and destructiveness (hence the title of the film). Quite clearly, the name of the game is racism, in its many forms, and the film manages to accurately portray it in all its terrible glory, with no apologies.

On text, it probably sounds preachy, yet the movie itself is not. In fact, the movie is, if anything, detached, leaving the reactions up to the viewer. But though the camera may be far off, the audience is not. It is difficult not to adore Daniel (Michael Pena), locksmith and loving father, or sympathize with Peter (Larenz Tate), a man who manages to be likeable despite his criminal profession.

It is winning performances like these that make Crash such a believable movie, even despite its rather implausible circumstances. (In a city as large as Los Angeles, it is extremely unlikely everyone would meet up in such a way, and even more unlikely that it would snow, which it does in the movie.) There is not one actor ill-fitted, not one character unbelievable. There are no clear-cut villains or heroes, with each having his or her moments of repugnance and benevolence. And so the very reality of the movie makes it all the more brutal.

In addition to superb acting, the cinematography and solemn, minimalist music — from bleak electronic tones to sparse choral arrangements — add to its quality. But to point out its cinematic merits seems beside the point, like reading a profound book and focusing only on its cover and syntax rather than its message. Crash is not a movie to be enjoyed, to be dissected, or to be analyzed; it is a movie to be absorbed, acknowledged, and contemplated. The film presents the problem of racism and presents no easy answer, because none exist. It is up to the viewer to take the message with them, and look inward.

It is a provocative film, one that may stir some deep or uneasy feelings in the heads of those who watch it. It made me uncomfortable, it made me angry, it made me cry, it made me walk out of the theater at the film’s end and yell a hearty “Fuck!” in the main lobby.

You may wonder what the point of seeing Crash would be. After all, it is an accepted fact that racism exists, and it is a problem. Seeing the movie is just a reaffirmation, or perhaps for some, a realization, of these harsh facts, and may very well motivate viewers to reassess their actions and change things for the better.

For that reason, Crash is worth seeing. It’s brutal, yes, and it’s depressing, yes (though it could have been much worse — see it and you will know what I mean). But it’s a valuable experience. And that is something very few movies can boast nowadays. See it.

Written by Richie DeMaria.