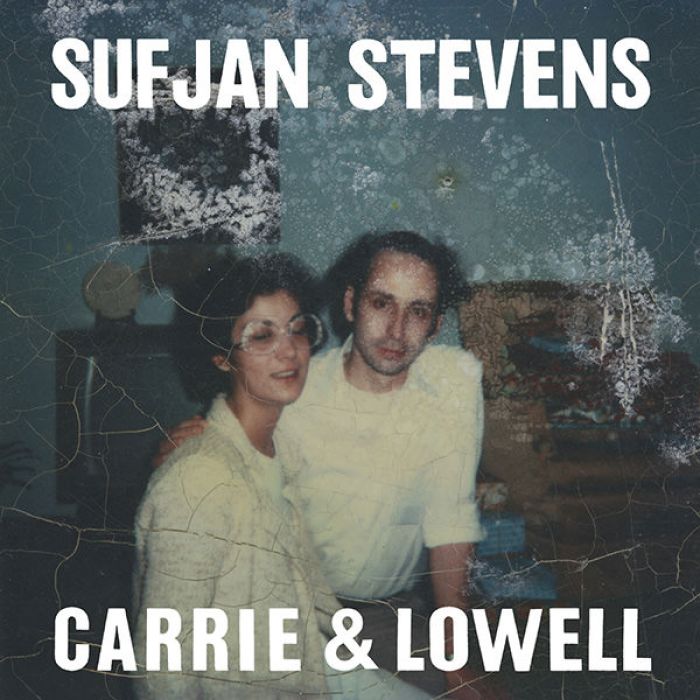

Sufjan Stevens Sings of Grief, Death, Love & Forgiveness on Carrie & Lowell (Review)

Many are calling Sufjan Stevens’ Carrie & Lowell his best album yet. Which strikes me as a bit odd — not because it’s not good (it is) but because it’s so unlike what we’ve come to expect from Sufjan as of late. This is the guy who wrote an elaborate symphony inspired by a New York City expressway and composed a soundtrack for a slow-motion rodeo documentary. In contrast, Carrie & Lowell contains precisely zero elaborate Steve Reich-meets-Vince Guaraldi orchestral arrangements, clever song titles, or overwrought high art pretensions. The album’s songs, some of which were recorded via iPhone in a hotel room, are simple, stark, and spartan — which is fitting considering the album’s tragic backstory.

The “Carrie” in the album’s title is Sufjan’s mother, who suffered from bipolar disorder, alcoholism, and drug addiction, and abandoned Sufjan’s family when he was just a year old. Although some reconciliation occurred during Sufjan’s childhood, Carrie’s absence clearly left a mark on Sufjan. She died of stomach cancer in 2012, and Carrie & Lowell is essentially Sufjan’s attempt to come to terms with her death, to make sense of her abandonment, and ultimately, find a place of peace and forgiveness.

Though the album is emotional and heartbreaking throughout — stripped of any geographical or historical wordplay, the lyrics here are Sufjan at his most personal and exposed — “Fourth of July” is Carrie & Lowell’s most wrenching moment. The song finds Sufjan beside his mother’s hospital bed as he watches her slip away, and the lyrics imagine a final exchange between them. As shivering drones and delicate piano notes float in the background, Sufjan sings of disappointment, last-ditch confessions, and even the absurdity of it all in a fragile whisper, and includes such devastating lines as:

Did you get enough love, my little dove, why do you cry?

And I’m sorry I left, but it was for the best

Though it never felt right

By the song’s end, Sufjan seems to realize that, for all of their differences, there is, in fact, one thing that unites him and his mother — and so he sings “We’re all gonna die.”

Death is no respecter of persons, and it waits for the rich and the poor, the mighty and the weak, the loved and the rejected alike. Ours is a culture terrified of death, and we do everything we can — we diet, exercise, invest billions in medicine and science, even create digital personas that will (hopefully) live on in some transhumanist future — to stave off that fearsome reality. Sufjan, however, confronts it head-on, and the great questions surrounding it. Not metaphysical questions like whether there’s a hereafter or not, but rather, questions of grief and reconciliation. How do you deal with the final absence of a loved one who was already absent for so much of your life? What do grievances compare to the impending death of the one who committed them? How do we forgive, and does forgiveness even matter? How do we acknowledge the good in people without diminishing the sins they’ve committed?

Sufjan has often wrestled with weighty subject matter (e.g., “Casimir Pulaski Day,” “John Wayne Gacy, Jr.,” “Romulus”) and as before, he resists easy answers here. Indeed, there may be no answers, but then again, how could there be? How do humans, limited beings that we are, make sense of something as final and strange as death? Even those of us who find solace in religion must, at the end of the day, admit to some confusion, anxiety, and lack of comprehension when faced with death’s inherent wrongness.

As the album progresses, though, Sufjan does seem to find a narrow ledge on which to stand. In “The Only Thing” he admits:

The only reason why I continue at all

Faith in reason, I wasted my life playing dumb

Signs and wonders: sea lion caves in the dark

Blind faith, God’s grace, nothing else left to impart

Later, in “John My Beloved,” he cries out:

Jesus I need you, be near,

Come shield me from fossils that fall on my head

There’s only a shadow of me;

In a manner of speaking, I’m dead

But fear and doubt still exist. “Fuck me, I’m falling apart,” Sufjan gasps near the album’s end on “No Shade in the Shadow of the Cross” (the title of which suggests that even faith doesn’t shield us from the doubts and sadness inherent to our limited existence).

To be honest, I do miss the usual Sufjan-isms: the elaborate, swirling arrangements that dominated Illinois, the eclectic multi-instrumentation, the whimsical banjo pluckings and woodwind trills (although this album’s use of steel guitar is a nice touch). Compared to his earlier efforts, Carrie & Lowell is uncomfortable to listen to, thematically if not musically. It’s painful to hear Sufjan sing about his mother leaving him and his siblings at a video store when he was “three maybe four.” But Sufjan’s music, unassuming as it is, won’t let me turn away — it won’t let me ignore the humbling, messy reality. (Or, as he puts it, “This is not my art project; this is my life.”) But reality it is, and Sufjan, well-known for the pomp and artifice in his music, explores grief, death, love, and forgiveness with such honesty, courage, and faith that I can’t help but admire it, and be humbled by it.