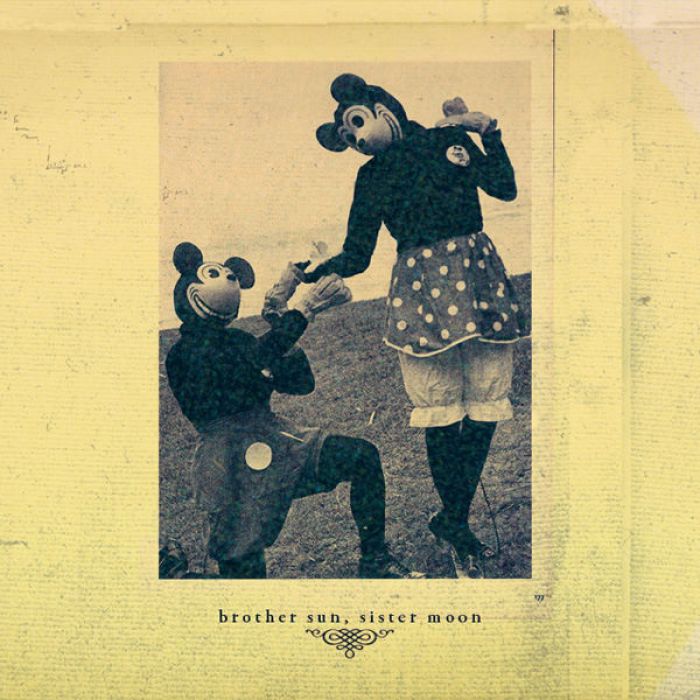

Brother Sun, Sister Moon by Brother Sun, Sister Moon (Review)

One of the supreme mysteries and delights of music is how mere sounds can inspire psychological and even physiological reactions. A guitar riff can get our heartbeat racing, a raucous beat can (sub-consciously) set our feet a-tapping, a melodic fragment can bring forth a laugh or two, some tears, and/or a poignant memory. This can be some pretty heady stuff to consider, and no doubt, artists, philosophers, and scientists will likely discuss and debate it ’til the end of time.

I bring this all up because in the case of Brother Sun, Sister Moon — the duo of Birds of Passage’s Alicia Merz and Roof Light’s Gareth Munday — their hazy aesthetic is an instant nostalgia trigger. It’s difficult for me to listen to these songs and not imagine that I’m listening to music culled, in some fashion, directly from the duo’s long-lost childhood memories.

I don’t want to read too much into their songs, if only because it’s difficult to make out what, exactly, Merz is singing, and yet… the drenching of Merz’s voice and Munday’s arrangements in reverb, echo, and vinyl hiss has the effect of tapping into a deep well of memory, one that comes pouring forth in their songs. Paradoxically, the more distant-sounding, removed, and amorphous the duo makes their music, the more affecting, haunting, and immediate it becomes.

Most of Brother Sun, Sister Moon finds itself quite content to meander through psychedelic folk country, with Merz’s cooing voice given a Gaussian blur treatment and sent drifting like a cloud over looped acoustic guitar, exotic flutes and drones, disembodied samples, and field recordings. It’s pleasant enough music, all pastoral and autumnal, but creepy as well courtesy of the echoes of children’s laughter that bubble up in songs like “Ghosts Of Barry Hill” and “From Grain To Flour.”

The album reaches its apex during a three-song “movement” in its second half. “Storms Break The Day” lifts a melodic fragment or two from the classic hymn “My Jesus, I Love Thee,” which immediately lends the song a contemplative tone that is aided by Merz’s reverb-laden vocals and Munday’s delicately-picked guitar. “From Grain To Flour” is a bit off-putting at first — the disembodied sounds of kids laughing is eerie in any case — but it becomes the album’s most blissed out moment, a shimmering swirl of guitars, trilling flutes, and field recordings that practically begs to be used as the soundtrack for those decaying 8mm home movies tucked away in your grandparents’ attic.

If “From Grain To Flour” represents the more upbeat and joyous side of nostalgia, then “South Downs By Morning” represents the more bittersweet and introspective end of the spectrum. Here, the album’s psychological effect becomes especially pronounced: the sad, sparse piano and field recordings (birds chirping, distant church bells) paint a picture of an ivy-covered town in the British countryside, and then set you down on one of its cobblestone streets. Merz’s otherworldly voice drifts around, beckoning you to follow, though it’s so blurred you can scarcely make out the shape of what she’s singing. (For what it’s worth, I imagine the song as a lament for some locale once beloved in childhood but now long gone, as an attempt to recapture and reimagine its former glory.)

Occasionally, Brother Sun, Sister Moon moves away from the folkier territory and towards something a bit more contemporary and beat-driven. But even then, their aesthetic remains in full effect. “One Throws And One Pulls” begins with a Caretaker-esque bit of orchestral manipulation before morphing into off-kilter atmospheric hip-hop. Elsewhere, “All You Need” blends hip-hop beats and shoegazer atmospherics à la the late, great Bowery Electric.

It feels a little strange to mention other artists when describing Brother Sun, Sister Moon. Sure, technically speaking, the album’s songs will bring to mind some obvious points of reference (a little Boards of Canada here, a little Flying Saucer Attack there). And yet, while listening to it, the comparisons fall away: the haziness that envelopes this album seems to hermetically seal it and make it its own thing. And once again, the paradox at the album’s heart re-asserts itself. Listening to songs like “From Grain To Flour” and “South Downs By Morning” pulls you out of the present and sends you meandering through unfamiliar, even spooky territory with little more than Merz’s disembodied voice to guide you. It’s discomfiting and entrancing at the same time, and haunting in every sense of the word.