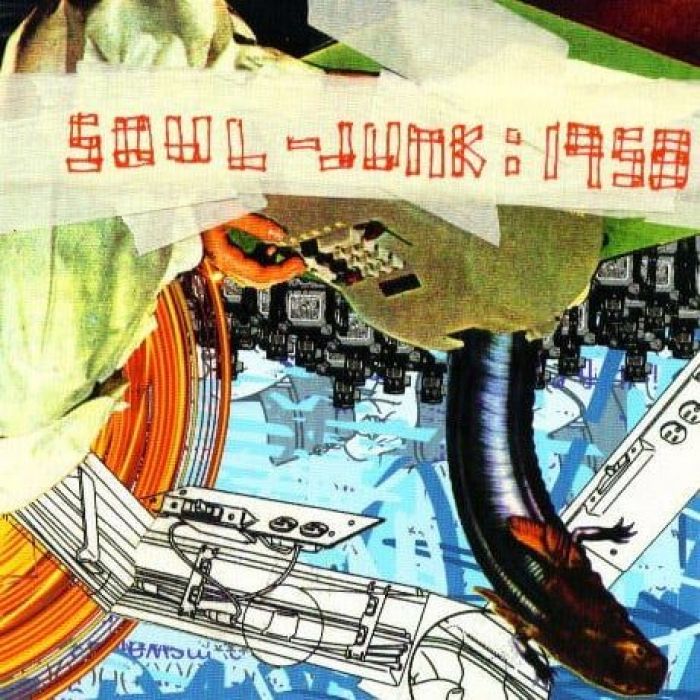

1958 by Soul-Junk (Review)

What can we make of Soul-Junk? What is “soul-junk,” what can it refer to? Certainly there are echoes of the two-person band’s early songwriting style, which came off as the merging of confessional and individual reflection, with short, bite-sized pieces of scripture redone to jumpy beats as a sort of vocalised collection of psalms. “Soul-Junk” — the array of references and citations from the Bible, thrown together as a deli smorgasbord, or a bachelor’s clothes closet. Spring cleaning for the soul.

But then a memory of the act’s earlier productions calls to mind that it once wasn’t so hip-hop, that once in true extension of Glen Galaxy’s former band Truman’s Water, we were smacked with truncated indie-rock songs, unravelling into free jazz, tightening into beats. “Soul-Junk” — the stylistic schizophrenia that has plagued (blessed) Slo-Ro and Galaxalag from moment one.

Late last autumn Soul-Junk released what is the high point of both of these aspects of their namesake in 1958, a record that punches holes through what the trained ear would classify as “beat-driven hip-hop,” and uses their inimitable, disparate production and lyrics to circumvent the destruction and negativity one might find in experimental music.

Culling samples from a variety of sources familiar and foreign — video games, elevator music, sound effects, and movie dialogue, to name a few — the tracks are built organically from simple stutter beats that jerk along with a conglomeration of elements added in succession on top, crowned at last with the vocals, delivered by Slo-Ro and Galaxalag as a tag-team.

Bizzart, a familiar name to the Sounds Are Active label, appears on two of the album’s best tracks, “Auto Smuddling” and “Buzzards.” Kidnastypup adds some spoken word rhymes on the penultimate track, “Mesa Dixie,” and works in my opinion more effectively with the scattered free-association of these cuts than the artists themselves. Describing the process of production is a lot less interesting than sitting down with the record and listening, but it is safer: sometimes the onslaught of noise after noise is virtually unlistenable, to some discredit to the album.

Other guests prove Soul-Junk’s propensity for equal eclecticism in production; free-jazz trumpeter Greg Kelley duels in abstract squiggles with the DJ scratches on “Hogging All the Islands” and Daniel Carter adds looped samples of flute and saxophone on “Long Of Tooth” in-between camera flashes and raw drum kit outlines. 1958 doesn’t mess with Soul-Junk’s long-earned formula of long verse rhymes and slothful steady beats. It just makes it busier, more abrasive, a pile of scrap material poised to collapse at the touch of an eyelash. Its complexity and its apparent fragility are delightful.

2003 was a productive year for experimental hip-hop artists, and especially for producers. Mush released undefinable gems by AWOL One with Daddy Kev, Omid, and Curseovdialect; Anticon blessed us with the fringe-hop of Why? and the machine-shop construction of Dosh. Elsewhere we were driven to look for cover by the confrontational Aesop Rock and the lazy cleverness of Josh Martinez. With an eye perhaps on higher goals than these beat phenoms, Soul-Junk can’t be denied entry into a still-emerging cadre of fresh artists, even though 1958 is their 9th album (counting forward from 1950). The virtuosity on display demands it.

Written by Joel Calahan.