Critics of Lovecraft’s Writing Are Missing the Point

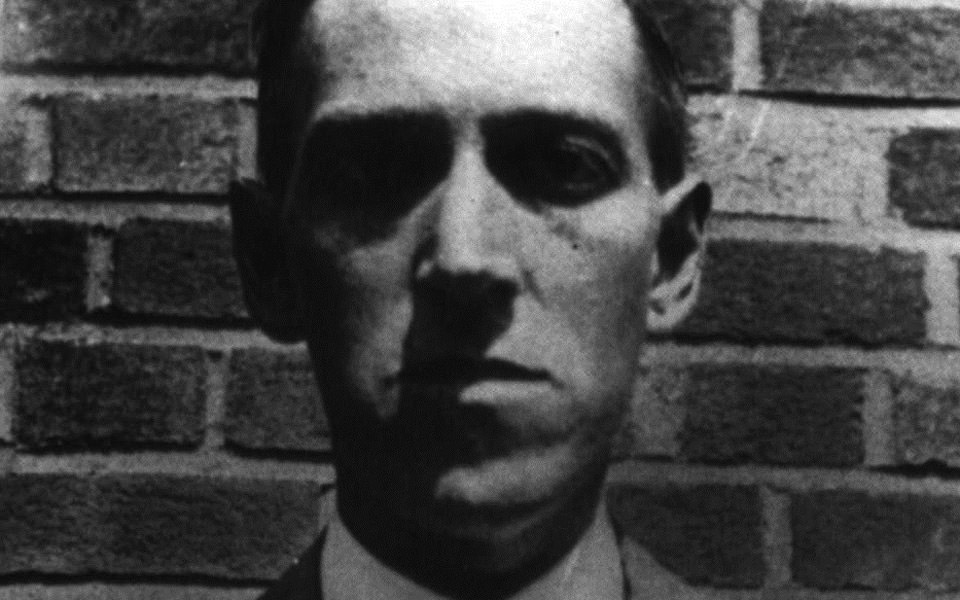

I love it that The American Conservative — home to conservative bloggers like Rod Dreher (who, by the way, is doing a bang-up job re. criticism of American involvement in Syria) — has recently come to the defense of H.P. Lovecraft in two recent pieces. First is Samuel Goldman’s “Cthulhu fhtagn: In Defense of H.P. Lovecraft, George R.R. Martin, and Other Bad Writers” in which he writes:

Lovecraft’s profound influence as a creator of worlds suggests that he was a better writer, in the crucial sense of articulating and communicating his ideas, than his more technically accomplished competitors. To criticize his stilted dialogue or Gothic affectations is to miss the point. Clumsy as he is, Lovecraft is remarkably good not only at transporting his readers to places that don’t exist, but at bringing them back with mementos from the journey. What more can we ask of a writer in the overlapping group of genres that includes SF, horror, and fantasy?

In other words, Lovecraft may, indeed, have been a bad writer from a technical standpoint — his prose could often be rather convoluted and purplish — but that’s beside the point. His world-building was second-to-none, and that’s what matters. However, Daniel McCarthy goes even further in “Literary Appreciation of the Lovecraft Kind” and claims “Lovecraft is certainly not on par with Coleridge as a poet, but he deploys quite effectively in a mere monster story effects of rhythm and sound that we conventionally identify with poetry.”

McCarthy points out that there is, indeed, a flaw in Lovecraft’s writing — “his stories are devoid of character development and all but the rudiments of a plot” — but this flaw is actually in service to an overarching philosophical point (i.e., humanity is insignificant, and therefore, not really worth describing in light of the universe’s monstrous truths). Or, as my Christ and Pop Culture colleague Geoffrey Reiter writes in his excellent piece on Lovecraft’s influence in Guillermo del Toro’s recent Pacific Rim (emphasis mine):

[L]ovecraft maintained that the human race was ultimately entirely insignificant and that to deny this insignificance was intellectually dishonest. To that end, the characters in Lovecraft’s works are almost exclusively bland. Though some of his protagonists exhibit an autobiographical curiosity about the terrible unknown, Lovecraft deliberately leaves them underdeveloped. Dialogue is sparse and mostly functional when it comes; women in general, and love interests in particular, are almost wholly absent. But none of this is an accident: Lovecraft doesn’t want you to care about his characters because he doesn’t care about his characters, because the cosmos his characters inhabit doesn’t care about them.

Lovecraft’s writing is absolutely wedded to the precepts of “cosmicism.” Which is why, nearly a century after his death, stories like “The Call of Cthulhu” and At the Mountains of Madness are still capable of awakening within us a certain sense of dread unlike anybody else.

On a related note, you can get all of Lovecraft’s works in one single free collection for your favorite Kindle, Nook, or other e-reader.