Considering Circle of Dust’s Legacy in Christian Industrial Music

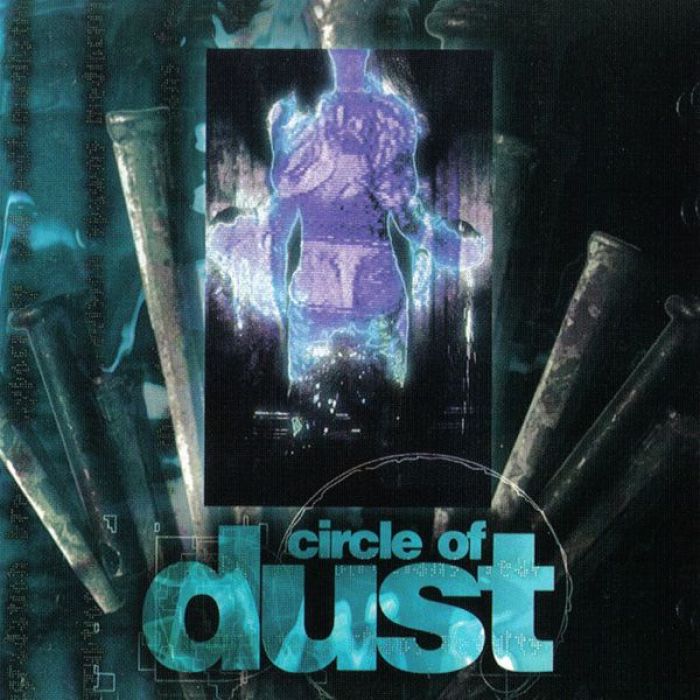

My latest “Chrindie ‘95” piece — a look back on Circle of Dust’s self-titled debut and its place in Christian industrial music’s history — was posted earlier this week.

There was a wave of Christian industrial music in the early ‘90s that has never been equaled since. Blackhouse — arguably the first Christian industrial artist — had been recording since the early ‘80s, but in the early ‘90s, artists including Mortal, Deitiphobia, The November Commandment, globalWAVEsystem, Generation, Under Midnight, and X-Propagation all released albums, some of them even on “big” labels like Intense Records and Metal Blade Records. But as influential and special as those albums were — for the record, I call dibs on Mortal’s Fathom if there’s ever a “Chrindie ‘93” project — Circle of Dust’s self-titled debut, in either form, holds a special place in the Christian industrial pantheon.

Though I cringe at drawing one-to-one parallels between “Christian” and “non-Christian” artists, it’s difficult not to think of Circle of Dust as the “Christian” Nine Inch Nails (with no offense intended to either artist). Scott Albert and Trent Reznor both knew how to balance aggressive beats and metal riffs with pop melodies and slick production, with the result being songs as catchy as they were intense.

Sadly, Circle of Dust was plagued with issues during its existence.

Their first label, R.E.X Records, experienced financial crises, layoffs, and legal issues in the mid ’90s, and [Scott Albert, Circle of Dust mastermind] spent over a year in legal disputes with them himself… The final Circle of Dust album, 1998’s Disengage, was released on Flying Tart Records, but Albert’s label woes continued even there. Flying Tart was bought out and the original owner fired shortly after Albert signed with them. Subsequently, Disengage was released in a mangled form and received little distribution.

Combine those headaches with the constant questions Albert received regarding his faith in light of his music’s darkness as well as his refusal to identify with the “Christian” market (an act far more controversial in the mid ’90s than nowadays), and it’s really no surprise that Albert abandoned Circle of Dust — and the Christian music scene — for other projects by the time the new millennium rolled around.

As is the case with a lot of these “Chrindie ‘95” pieces, there’s a lot of “what if?” questions that start swirling around. What if Albert had received better support from his labels? What if the Christian market had been more gracious and thoughtful in its reactions to his music? What if he’d continued recording as Circle of Dust instead of various other projects (e.g., Angeldust, Celldweller)? We’ll never know the answers to such questions, but it’s hard to not ask them and wonder.

Most industrial music fans will probably roll their eyes at this comment, but for me, the early-to-mid ’90s contained a veritable goldmine of great industrial albums that, though Christian, certainly hold their own against a lot of what non-Christian artists were doing at the time. To this day, when I think of industrial music, Circle of Dust, Under Midnight, Mortal et al. are usually the first artists that come to mind.