A Bit of a Ramble on Sci-Fi, Spirituality, Atheists, Babylon 5 & Firefly

There’s been an interesting debate/discussion on one of the forums I frequent. The debate was essentially about whether or not science fiction could ever be spiritual (specifically science fiction cinema). The point was made that so much of sci-fi denies the existence of God, either because it simply doesn’t include God or denies Him outright (perhaps by embracing a humanist mindset a la Star Trek).

All in all, it’s been a very interesting and rewarding discussion to follow and take part in, eventually moving beyond just sci-fi, and on to asking questions about just what kinds of art a Christian can/should deem spiritual.

Is it possible to find great worth and spiritual meaning, perhaps even “Christian” spiritual meaning, in a work by an agnostic, or perhaps more important, an atheist? That’s a thing that many Christians seem to stumble over and wrestle with, and for obvious reasons. What good does it do to ingest the works of someone who has outright denied God’s existence? Is there any possible merit to be found in them? How do we do “Christian” readings of such materials, or is it even worth the effort to do so?

My own personal opinion is that all truth is God’s truth and that non-believers, even those who completely deny the existence of God and rage against the faith, are still human beings made in the image of God. As such, they’re still imbued with His creative spirit — their lack of faith doesn’t diminish it one bit — and as such, anything they create can be valid, praiseworthy, and deserving of respect, criticism, and consideration.

And because they’re still human beings, they’re still completely capable of asking “important” questions about existence, human nature, our place in the world, etc. Indeed, it seems like they often ask them better than Christians do, simply because they’re not loaded down with all of the religious and cultural baggage that we Christians so like to carry.

When I look at the great sci-fi films — Blade Runner, 2001, Solaris, Stalker — I see films that ask those “important” questions, that wrestle with man’s place in the cosmos, with what it means to be human. (Although, to be clear, the director of Solaris and Stalker, Andrei Tarkovsky, was a Christian.) Even pop sci-fi like Star Wars and The Matrix asks these questions, albeit in a slightly glossier manner, and can cause us to think of reality in grander, more mythic terms.

Films such as Ghost in the Shell and even The Terminator raise questions about our responsibilities to our creation (in this case, technology), and posits what happens if we start over-stepping our bounds and begin “playing God.” Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind also raises questions about human nature, as well as of love and forgiveness.

Granted, sci-fi, along with horror and fantasy, lends itself quite well to senseless and base spectacle, where the quality of the CG explosions is more important than the quality of the plot, and the skimpy outfit of the female lead is given more credence than the questions the film is supposedly trying to raise.

But sci-fi, along with horror and fantasy, also has great power to take us outside of ourselves, to raise questions using allegory and metaphor, which is sometimes more effective than just coming right out and making an obvious statement. They can awaken our sense of awe, inspire us to dream much bigger dreams than we could have before, and introduce us to new mysteries and wonders in ways that, say, a romantic comedy just can’t.

Going back to one of the original questions — is it possible for Christians to find spiritual meaning and truth in works by non-Christians — there are two examples that immediately come to mind that answer that question once and for all.

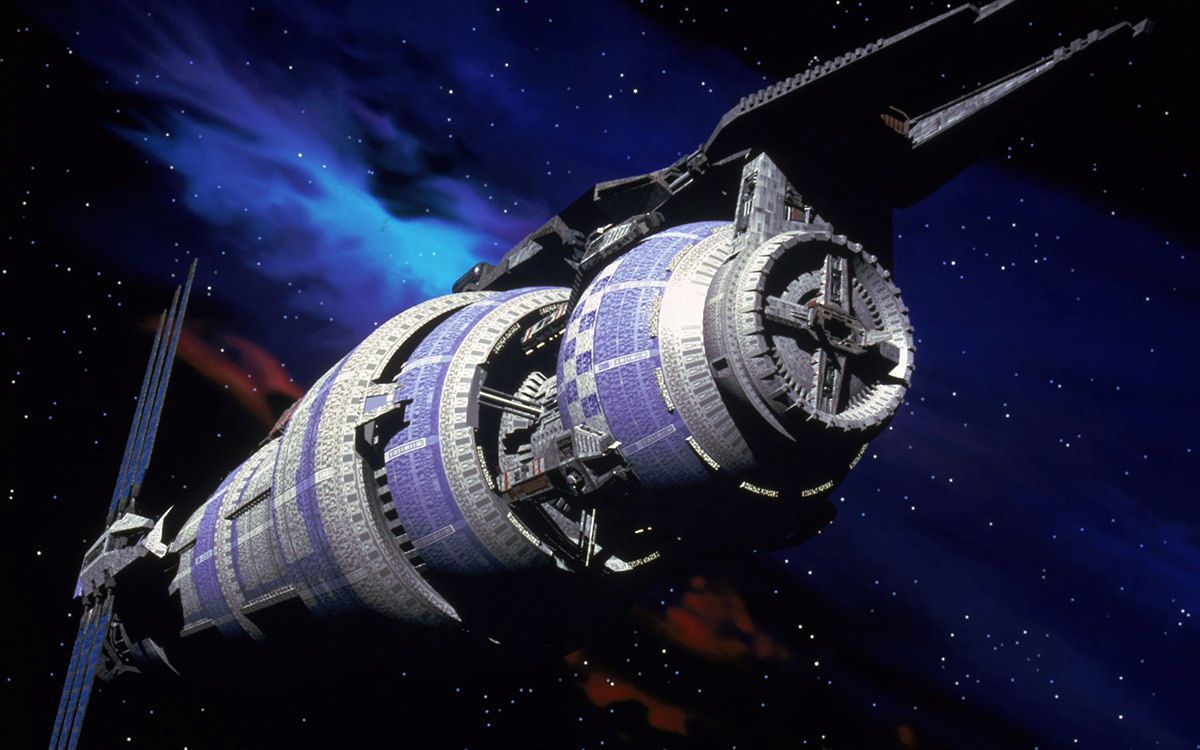

For the past few months, some co-workers and I get together once a week to watch Babylon 5 during lunch. I caught a good portion of the show when it originally aired back in the late ’90s, but back then, I was still very much of a Trekkie, so it played second fiddle.

Watching it now, it’s obvious the show hasn’t aged too well in some areas — the costumes, sets, and whatnot all stand out as products of the late ’90s — but I have come away with a greater appreciation for the plot, the character developments, and its “messy,” more complex view of humanity (which stands in stark and blessed contrast to Star Trek neat and tidy view of enlightened humanity). The most recent episode we watched, “Passing Through Gethsemane,” deals with a priest (religion is still present in Babylon 5’s vision of the future, and portrayed as an important part of characters’ lives, another difference with Star Trek) who begins to suspect some terrible things about his past.

It’s one of my favorite episodes, and it raises all manner of questions. What is forgiveness? Can we be forgiven for crimes we don’t even know we committed? How far should society go to punish those who commit terrible crimes? How do we find redemption? It’s interesting to note that the episode deals heavily in Christian imagery, and in quite a thoughtful and respectable manner, and yet the creator of Babylon 5, J. Michael Straczynski, is an atheist. When asked about the ideas behind the episode, and the message he was trying to convey, Straczynski had this to say:

I have lost people. Too many people. Lost them to chance, violence, brutality beyond belief; I’ve seen all the senseless, ignoble acts of “god’s noblest creature.” And I am incapable of forgiving. My feelings are with G’Kar, hand sliced open, saying of the drops of blood flowing from that open wound, “How do you apologize to them?” “I can’t.” “Then I cannot forgive.”

As an atheist, I believe that all life is unspeakably precious, because it’s only here for a brief moment, a flare against the dark, and then it’s gone forever. No afterlives, no second chances, no backsies. So there can be nothing crueler than the abuse, destruction or wanton taking of a life. It is a crime no less than burning the Mona Lisa, for there is always just one of each.

So I cannot forgive. Which makes the notion of writing a character who CAN forgive momentarily attractive… because it allows me to explore in great detail something of which I am utterly incapable. I cannot fly, so I would write of birds and starships and kites; I cannot play an instrument, so I would write of composers and dancers; and I cannot forgive, so I would write of priests and monks.

The second example comes from Firefly, another sterling work of sci-fi created by an atheist, Joss Whedon. One of the series’ main characters is a priest who has left his monastery to travel for a bit and try and do some good. He becomes a real, vital moral compass for the rest of the characters, has intelligent and thoughtful religious debates, commits acts of mercy and justice, and befriends those who are despised and disliked by the others. In fact, he’s probably one of the best “Christian” characters I’ve seen on any show in recent memory.

As I think on these two examples, I find myself asking a very different question. Not “Can Christians find value in the works of non-Christians, even atheists?” but rather, “Would a Christian be just as willing to include characters in their show/movie/book whose beliefs are completely antithetical to their own, and portray them as thoughtful, intelligent, considerate human beings rather than as caricatures or infidels who simply need to be converted?”